In May 2015, the UK held a general election and returned a majority government for the Conservative Party despite the fact that it received no where near a majority of support from the electorate. The Electoral Reform Society is an independent campaigning organisation working to champion the rights of voters and build a better democracy in Britain. Today they published a report showing how unrepresentative the British Parliament now is and put forward some suggestions for how it would look under different systems. By kind permission of the ERS we publish part 1 of their report here. The full report can be found by clicking here, and you can follow the Electoral Reform Society on their Twitter and Facebook accounts using these links.

The 2015 election was from the outset always going to be unusual. This was the first post-war election held after a period of coalition government; the first in which seven parties shared airtime with each other; and the first in which, thanks to the introduction of fixed-term Parliaments, the date of the election was known years in advance (making the Prime Minister’s visit to the Palace purely for show). Whilst this most unusual of elections did not deliver the result the pollsters predicted, what it did deliver was a damning verdict on First Past the Post.

With another hung parliament expected by all pollsters, the result shocked many as the Conservative party secured enough seats to form a government with a slim majority. The one feature of the result that was not a surprise was the continued dysfunctionality of the electoral system. In the most disproportional election to date in the UK, millions voted for smaller parties only to see their efforts result in single-digit representation, and a majority government returned to Parliament on less than 37% of the vote and with the support of just 24% of the electorate. The two-party system has long been dead, but if the 2015 election is known for one thing, it will be for the entrenchment of multi-party politics across the whole of the UK.

The First Past the Post system continues to fail the British electorate, not only by failing to accurately reflect their wishes but by creating divisions which do not really exist. The electoral system is effectively splitting the Union, exaggerating differences to create national and regional divides. The Union survived Scotland’s independence referendum, but now the electoral system – and the artificial cleavages it creates at Westminster – is exacerbating the divides between the nations and regions of the UK.

The votes are in

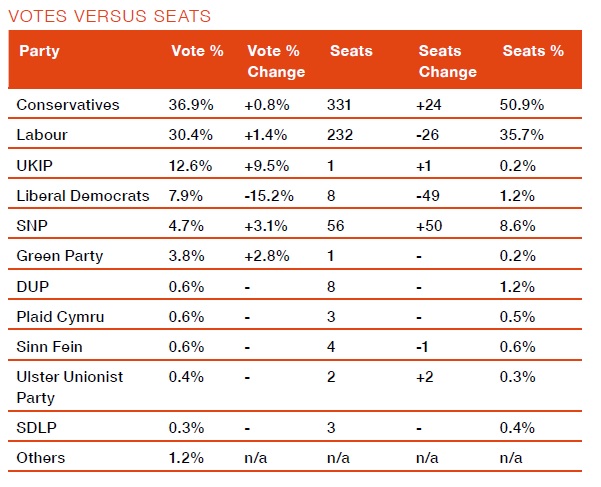

Votes for the two largest parties came to just 67.3% combined, with 36.9% of the electorate voting Conservative and 30.4% voting Labour. The number of votes cast for parties other than the Conservatives, Labour or Liberal Democrats on the other hand, rose to its highest ever level (24.8%) – nearly a quarter of the votes cast (up from 11.9% in 2010).

Over ten million people voted for the UK Independence Party (UKIP), the Scottish National Party (SNP), the Liberal Democrats, Plaid Cymru, the Green Party and other smaller parties – a third of all votes cast. Yet whilst the SNP managed to translate support into electoral success, elsewhere these votes have little weight in a system designed to favour the two largest parties.

If viewers of the televised leaders’ debates thought they were witnessing something from Borgen rather than Yes Minister, the tables have turned now MPs have returned to Parliament where the creaking status quo still holds. Voters’ preferences are once again not reflected in the make-up of the House of Commons. At both a UK wide level and also within the nations, votes bear little relation to seat share.

In 2010 the Conservative and Labour parties secured 65% of the vote and 87% of the seats. This year the system has delivered a similarly disproportional result for the two largest parties, with just over 67% of the vote resulting in nearly 87% of the seats for these two parties. The Conservatives and Labour have even greater disproportional sway in England and Wales, with 98% of the available seats between them on 72.6% of the vote.

Neither of the two largest parties has achieved anywhere close to 50% of the vote in the UK for over 40 years. That trend continued in 2015, with the Conservative party now governing on less than 37% of the popular vote. It seems highly unlikely that either party will return to their previous levels of support. Multi-party politics looks firmly established in the UK and yet we continue to use an electoral system designed for a time when just two political parties shared nearly all the votes; a situation that has not existed in the UK for decades.

The lottery election

Westminster election results are becoming not only increasingly disproportional but also more random, with results reflecting more of a lottery than a true representation of the vote. When several parties gain significant support, the First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system behaves erratically and, as expected at this election, the combination of party fragmentation and FPTP has led to some strikingly irregular results.

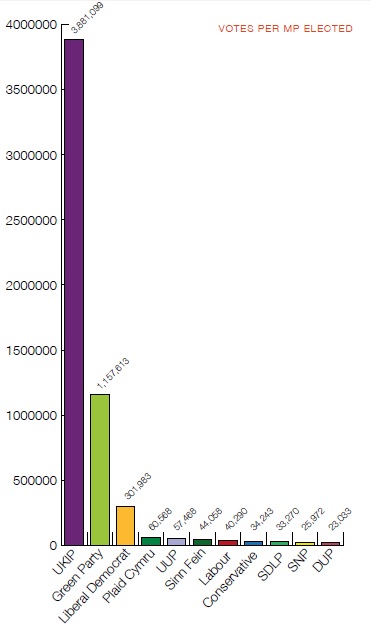

Support for UKIP surged at this election, making the party the third largest on vote share nationally (12.6%), overtaking the Liberal Democrats (who dropped from 23% to 7.9%). Yet this remarkable result delivered UKIP just one Member of Parliament. The Conservative party received three times as many votes but 331 times as many MPs.

The SNP also had a great election in terms of vote share. They received 4.7% per cent of the national vote share (up from 1.7% in 2010) and 50% of the vote share in Scotland. This was indeed an impressive result, higher than Scottish Labour’s best figure of 49.9% in 1966 (which returned 46 out of 71 MPs). Yet this result was magnified and translated from a landslide into a tsunami, resulting in 95% of Scottish seats. This leaves only three MPs (5% of the total) to reflect unionist support in Scotland – a body of opinion that received 55.3% of votes in the referendum in 2014. While the SNP have clearly gained support from ‘No’ voters as well as from the ‘Yes’ camp, that there is such a small unionist voice in Scotland is a further reflection of a broken electoral system.

The 2015 election has highlighted the randomness of FPTP when party votes fragment. There have been electoral injustices not just for smaller parties. Labour and the Conservatives, whilst the clear winners under the system in England, have been dealt an unfair hand in Scotland. Labour continues to be under-represented in Southern England and the Conservatives likewise in the North. The system exacerbates the regional polarisation of the electorate.

The uneven results thrown up by the system can be illustrated by looking at how many votes were cast for the number of seats gained overall. The Green Party was able to work with the way FPTP rewards geographical concentrations of votes in order to hold Brighton Pavilion, but it still received only one seat for the 1.1 million votes cast for the party nationally. UKIP received over 3.8 million votes nationally and yet also returned just one MP to Parliament. By comparison the Conservative party required on average just 34,000 votes per MP.

Concentration of votes is a key factor under FPTP. Parties with substantial support spread across Britain do less well in making those votes count than parties who are concentrated in particular areas.

Another factor of our broken system is the ever-decreasing percentage of support for the governing party. Since 2001, no single-party government has commanded the support of more than 40% of voters. This trend continued this year with the Conservative party securing a majority, albeit slim, on just under 37% of the votes. Whilst rightfully able to form a government on the basis of seat share, a government is weaker in terms of legitimacy if it is elected by little more than a third of voters; a figure that decreases when we consider the rate of turnout. Taking turnout into account, the current government commands the support of just a quarter (24.4%) of the registered electorate.

We may have returned to single party government for this Parliament but this does not mean a return to stability FPTP is said to deliver strong and stable single-party governments. We may have returned to single party government for this Parliament but this does not mean a return to stability. Although it is early days, the government may well struggle to pass all its legislation with such a small majority and the Fixed Term Parliaments Act could leave it in the strange position of being unable to pass its legislative programme and yet prevented from calling another election. Coalition government attracted scepticism, but against expectation delivered stable government in 2010-2015. In the coming years, the current administration may at times look back fondly on the 78-seat majority the coalition government of the last parliament commanded.

FPTP is out of date and unfit for purpose. The system cannot cope with the choices voters are making in this multi-party era. People are choosing to vote for a wider range of parties and our electoral system should be able to reflect that in the composition of Parliament. Parties should not be penalised for reaching out and trying to build support across the country rather than just in target areas. We are becoming a more electorally diverse and complex society. It is much more sensible to change the system to reflect this, than to hope that voters go back to supporting just two parties.