As part of the activities carried out by the thematic roundtables on Internal development, Education, and Gender based violence within the framework of the World Humanist Forum, humanist activists launched a program on Valentine’s Day in the Kenyan maximum-security prison of Kisumu Kibos that seeks to promote the internal renewal of inmates.

By Dorothy Adenga and Javier Tolcachier

The program aims to base rehabilitation in prisons on internal development, self-liberation, and self-realization, strengthening emotional awareness, resilience, and personal responsibility among inmates.

It also aims to integrate awareness of gender based violence to promote responsibility, respect, and nonviolent norms, as well as to support education and life skills as pathways to long-term reintegration. While providing safe and participatory spaces for dialogue, reflection, and expression, the project seeks to foster leadership and commitment with the support of peers in similar situations.

The strategic goal is to establish a sustainable and replicable rehabilitation model within penitentiary institutions.

The program, which focuses on the inmates’ own work, is delivered through dialogue, recordings, reflective circles guided by self-inquiry, collective learning, gentle integration, and experiential learning. The sessions address self-awareness, emotional regulation, responsibility, life skills, education, awareness of gender-based violence, and the creation of hope.

Groups of 35 to 40 inmates participate in weekly or biweekly sessions where they are provided with writing and learning materials so they can keep their own records while sharing refreshments and also review the session in their free time. The sessions are reinforced through reflection exercises, creative expression, and planned graduations and talent shows that affirm progress and achievements.

Through the World Humanist Forum, the team carrying out the project established a collaboration with an Argentine group that has been working in prisons for several years, implementing eight modules and planning a graduation ceremony for inmates before they are transferred to prepare for their release.

Background

The Love Without Limits initiative was first publicly presented in 2025 in Kisumu, on Valentine’s Day, when flowers were distributed to police officers in public spaces. This activity was deliberately designed to challenge fear, stigma, and social distance, affirming that police officers are normal human beings who deserve dignity, empathy, and humane treatment, and should not be feared or isolated.

This public action laid the conceptual foundations for “Love Without Limits”: dismantling fear, restoring dignity, and normalizing compassion. These principles subsequently inspired the application of the initiative in prison settings.

On this basis, the program was afterwards implemented in 2025 at the Borstal juvenile correctional center in Mombasa, involving young inmates under the age of 18. The focus shifted from public humanization to internal development, recognizing that incarceration often intensifies emotional isolation, identity erosion, and internalized stigma, especially among juvenile offenders.

Following its positive reception and observed results, the program was expanded to the Kisumu Kibos maximum security prison, extending the same human-centered and reflective approach to adult male inmates. Although the prison context was different, the core philosophy remained constant: meaningful rehabilitation.

The Valentine’s Day activity served as the formal launch of the program at Kisumu Kibos maximum security prison, under the theme “Love Without Limits.” The activity was intentionally structured as a human-centered intervention, prioritizing emotional balance, trust building, and an introduction to sustained inner development.

Humanist Rose Neema opened the session with a guided relaxation exercise, allowing participants to release tension and become emotionally present. She then introduced the Inner Development Thematic Table of the World Humanist Forum, emphasizing self-liberation and self-realization as processes through which inmates can regain inner freedom, responsibility, and dignity despite physical confinement.

Humanist Dorothy Adenga complemented this activity with an interactive dialogue, inviting inmates to reflect on love, connection, abandonment, forgiveness, and hope. The discussion was intentionally framed as a conversation, allowing participants to express their experiences and perspectives in a safe and respectful space.

Dorothy reported that the prison provided a space for a “conversation wall” with humanist messages and invited artist inmates to collaborate, for which the team needs to obtain paints and materials.

The institution assigned a small number of prison officers to support the program, ensuring order and continuity. At the same time, inmates volunteered to support the sessions, helping with logistics such as preparing materials and managing the PA system. This shared responsibility demonstrated willingness, accountability, and commitment, and both staff and inmates expressed their desire for the program to continue.

Valentine’s Day gift package

In a spirit of compassion and recognition, emphasizing dignity, care, and shared humanity, roses were given to inmates and staff on Valentine’s Day, a meaningful and unforgettable gesture. The fumigation of cells infested with bedbugs was also self-funded, as the government had not provided this service.

The distribution of roses to inmates by Rose and Dorothy on Valentine’s Day was a deliberate symbolic act to soften emotional barriers, break down institutional distance, and see them as human beings, accompanied by the message #I see you in me. This gesture humanized the engagement, evoked an emotional connection, and reinforced the message of inclusion, recognition, and care.

In addition, gift packages were given to staff and inmates as a symbolic act of gratitude for their daily efforts and resilience. Among the gifts was underwear, a simple but meaningful present that affirms their dignity and reminds them that they are seen and valued as human beings.

Through these gestures, the initiative went beyond the delivery of materials: it was a humanist act, based on empathy, respect, and recognition of shared humanity. It was a moment to remind everyone, regardless of circumstances, that care and kindness transcend walls, uniforms, or roles.

Staff commitment and institutional support

While inmates remained the primary beneficiaries, the program’s effectiveness was enhanced by institutional cooperation. Prison officials and social welfare officers provided authorization, oversight, and structural support, ensuring a safe and conducive environment for participation.

Among the officials, the collaboration of Billy Koshal (ACGP), Deputy Commissioner of Prisons, and Timon Warambo (S.W.O), Senior Social Welfare Officer, was noteworthy.

Staff recognized that human involvement and internal development initiatives contribute positively to inmate rehabilitation, institutional culture, staff morale, and inmate-staff relations.

Inmate involvement

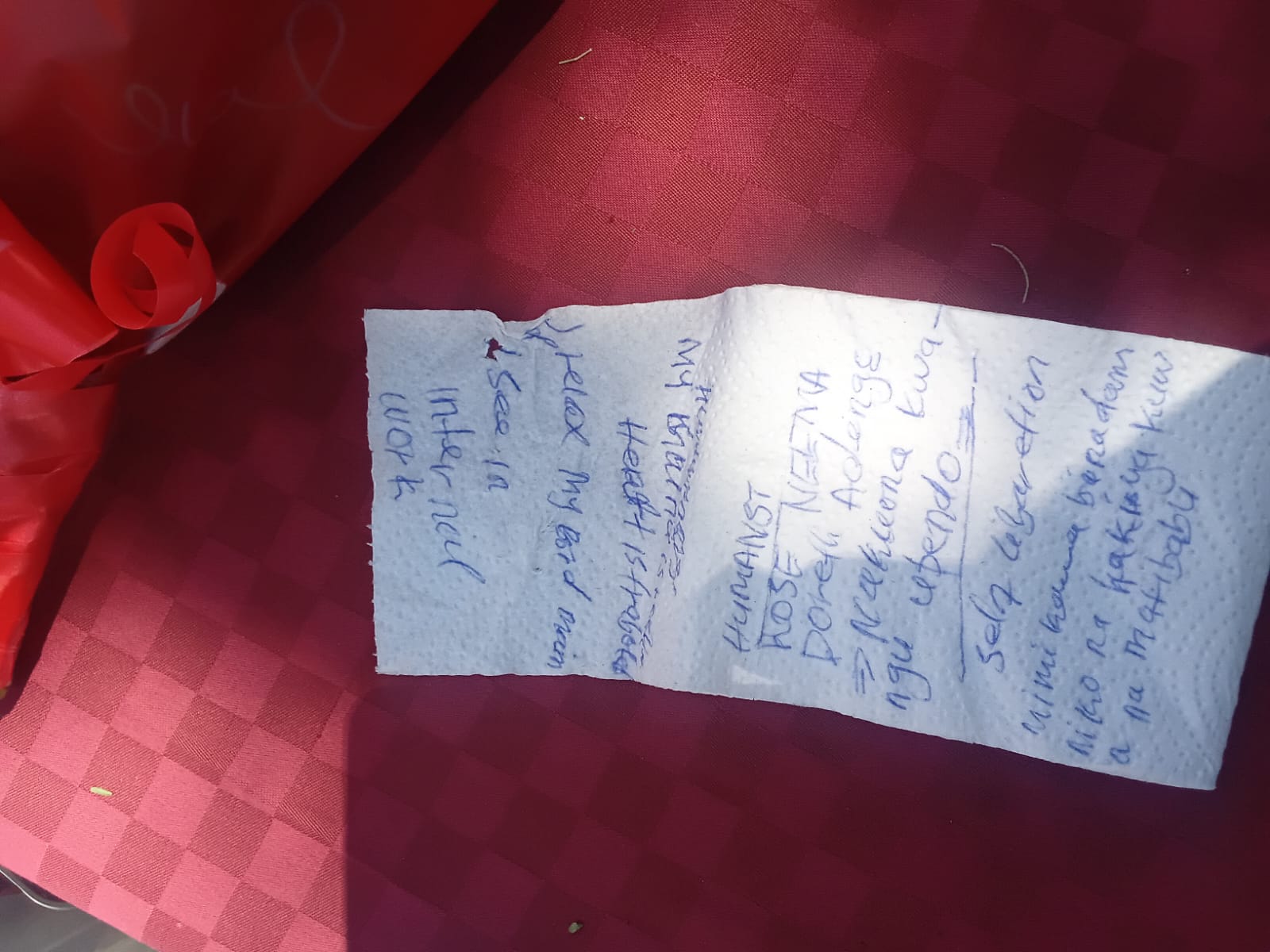

Inmate involvement was active, thoughtful, and deeply personal. Participants demonstrated attentiveness and emotional openness throughout the session. One participant wrote down key lessons on a tissue, highlighting both resource constraints and the value placed on the teachings.

“Since I was incarcerated, my family stopped calling me, and when I call them, they don’t answer. But today, when I received these flowers, I felt that I still belong somewhere”, said another participant.

Inmates consistently expressed feelings of gratitude, emotional relief, and renewed hope.

Creative expressions such as singing, movement, and storytelling allowed for emotional processing beyond verbal discussion. These activities fostered trust, connection between peers, and a sense of shared humanity.

Impact and conclusions

The program demonstrates that internal development interventions based on dignity, participation, and compassion can positively influence the emotional stability, self-awareness, and resilience of male inmates. Furthermore, the integration of symbolic gestures with structured participation reinforced the outcomes of rehabilitation and institutional harmony.

The Valentine’s Day activity successfully introduced a long-term internal development program based on humanity, introspection, responsibility, and transformation.

Key recommendations based on experience underscore the importance of continuing the program to reach at least three-quarters of the prison population and other additional correctional facilities. Fundamental aspects for the project’s progress include securing ongoing institutional support and involving inmates themselves in leading activities.