For decades, Canada was presented as a calm antidote to U.S. political radicalization: stable federalism, formal recognition of Indigenous peoples, and a sober institutional culture. That image has now cracked in Alberta, where an apparently provincial political crisis is beginning to take on unsettling international contours.

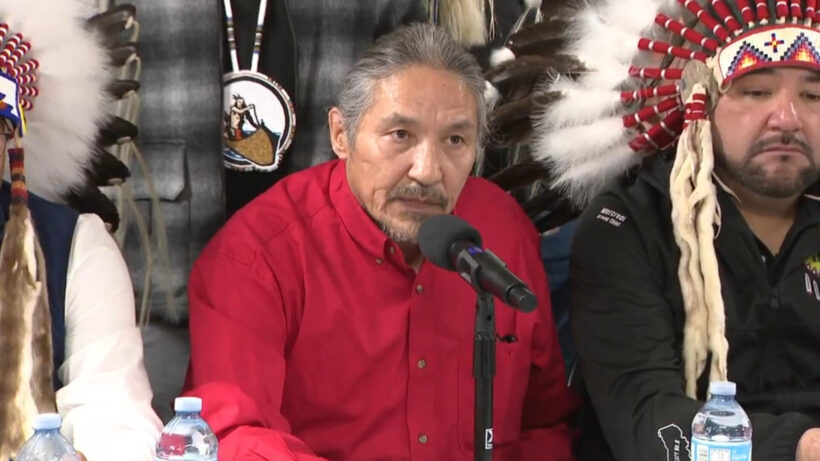

The public statement by the First Nations of Treaties 6, 7, and 8 — demanding the resignation of Premier Danielle Smith and denouncing the promotion of an unconstitutional separatist project— is neither a symbolic gesture nor a local dispute. It is an early warning signal. And the question already circulating in diplomatic and academic circles is uncomfortable but legitimate: is Alberta becoming a new laboratory of Trumpism outside the United States?

The fact

The immediate trigger is the legal reform pushed by Danielle Smith’s government that facilitates the calling of provincial referendums. Although the text does not explicitly mention independence, separatist sectors interpreted it as a green light to attempt a referendum on Alberta’s secession from the Canadian state.

In response, the chiefs of the First Nations were categorical: any attempt at separation would be illegal, unconstitutional, and in violation of the historic treaties signed with the Crown, which predate Alberta’s very existence as a province. In that context, they accused the premier of actively legitimizing a project that threatens the constitutional order and demanded her resignation.

The harshness of the language —including the viral phrase “when this referendum is defeated, I will gladly walk you to the border”— does not express violence, but political rupture. A rupture that can no longer be reversed through tepid communiqués.

The broader framework

The conflict cannot be understood without observing the international context. Since Donald Trump’s return to the center of the U.S. political scene, a familiar logic has reemerged: the weakening of federalism, the exaltation of fragmented sovereignties, contempt for constitutional law, the instrumentalization of regional resentment, and a direct attack on Indigenous peoples as “obstacles” to development.

Alberta displays all the classic ingredients of that script.

A political elite that presents itself as a victim of an “oppressive central state.”

An anti-federal discourse fueled by the extractive industry.

An explicit rejection of environmental and fiscal regulations.

A narrative of provincial “sovereignty” detached from law and history.

This is not an isolated phenomenon. It is the Canadian translation of an exportable ideological matrix.

Is there a connection to Trump?

There is, for now, no direct documentary evidence of formal coordination with Donald Trump’s inner circle. But serious analysis is not limited to money transfers or secret meetings. Political influence today operates through ideological communication vessels.

Danielle Smith has shown open affinity with Trumpist positions: confrontation with the federal government, disdain for scientific consensus, anti-elite rhetoric, radical defense of extractivism, and the normalization of institutional rupture as a tool of political pressure.

What is observed in Alberta is consistent with the trumpian manual: winning the referendum is not the point; eroding the legal framework, polarizing society, and forcing the state to negotiate from chaos is.

First nations as a limit

Here emerges the element that deeply unsettles that strategy: Indigenous peoples.

Unlike other separatist scenarios, Alberta cannot erase its founding history. Treaties are neither folklore nor symbols: they are binding constitutional law. And the First Nations recalled this with devastating clarity: without treaties, Alberta does not exist.

This is the point that Trumpism —in any of its versions— does not know how to handle. Indigenous peoples do not fit into a simplified sovereignty narrative because they introduce memory, legality, and limits.

Systemic risk

If Alberta’s government persists in flirting with separatism, the conflict will inevitably escalate on three levels.

A direct clash with the Supreme Court of Canada.

The reopening of Indigenous sovereignty over treaty lands.

The weakening of Canada’s image as a stable rule-of-law state.

This last point is not minor. In a world where authoritarian projects seek to expand through ideological contagion, Alberta could become the first case of serious institutional destabilization within the G7 driven from a province.

This is not only about Danielle Smith. Not only about Alberta. What is at stake is whether Canada allows an imported logic —trumpism as a method— to erode its constitutional architecture from within.

The First Nations have done what law and history allow them to do: draw a red line.

The question now is whether the Canadian state will know how to read it before the experiment spirals out of control.