From the “end of history” to the beginning of a new contradiction. Or how a Pinochet supporter managed to captivate an electorate he does not represent.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s not only marked the end of the Cold War, but also inaugurated a period of uncontested Western hegemony led by the United States. This moment was interpreted by many as the definitive victory of liberal democracy, with some even proclaiming the ideological “end of history.” However, far from consolidating a world of stable liberal democracies, the last three decades have revealed a profound paradox: the unipolar order and the geopolitical transformations it propelled created the conditions for the decline of the very system of representative democracy it sought to universalize. This essay argues that the loss of the Soviet counterweight unleashed a set of geopolitical, economic, and ideological dynamics that, combined with the intrinsic weaknesses of the liberal democratic system, have facilitated the global rise of illiberal democracy. This hybrid model, which maintains an electoral façade while eroding the rule of law and civil liberties, is not an accident but the symptom of a systemic crisis connecting the end of bipolarity with contemporary discontent.

The geopolitical vacuum and the transformation of democracy into a tool

With the disappearance of the USSR, the great ideological counterweight that had provided cohesion and a sense of civilizational mission to the Western bloc also vanished. This vacuum had fundamental consequences.

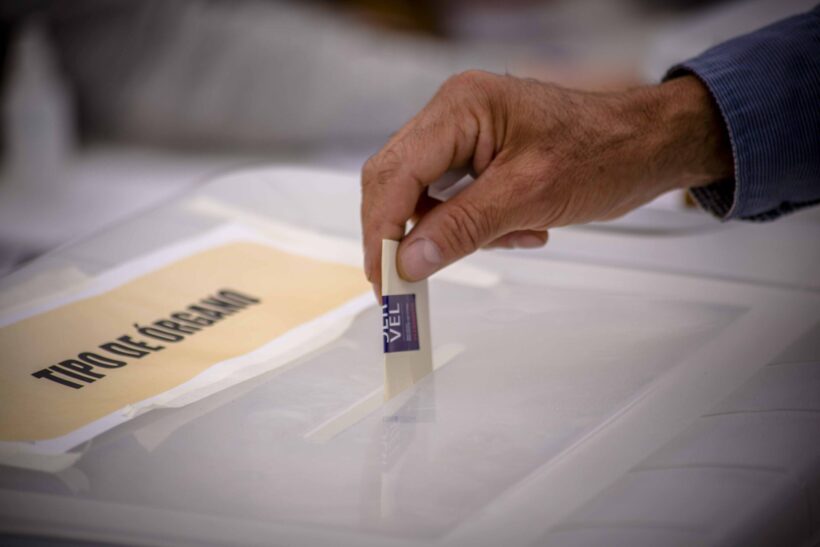

First, it led to an overexpansion and trivialization of the democratic model. Without an existential rival, the promotion of democracy became, in practice, a simplified tool of foreign policy, reduced to the celebration of multiparty elections without the necessary parallel construction of strong liberal institutions (rule of law, separation of powers, civil liberties). This “electoral fetishism,” as criticized by Fareed Zakaria (who coined the term “illiberal democracy” in 1997), allowed the emergence of “hybrid regimes.” These systems learned to use the ballot box as a ritual of legitimization, but once in power, their leaders ignore, bypass, or systematically elude the constitutional limits on their authority.

Second, unipolarity eroded the performance-based legitimacy of Western leadership. The absence of ideological competition meant that the failures of the model—costly and inconclusive wars, the 2008 global financial crisis, and increasing inequality—were perceived not as correctable problems but as essential flaws of the global liberal establishment. This sense of betrayal fueled discontent that domestic political actors began to capitalize on through anti-elite and anti-system discourse.

The anatomy of illiberal democracy: Ideology and method

Illiberal democracy is not a classical dictatorship but a regime that maintains a complex and paradoxical relationship with democratic forms. Its essence is the rejection of liberal pluralism, replaced by an exclusionary ideology based on the primacy of a homogeneous national, ethnic, or religious majority.

The ideological pillars of illiberalism revolve around key concepts: the nation (understood in a nativist and cultural way), religion (as a public moral foundation contrary to secularism), the family (traditional and heteronormative, as the antithesis of individualism), and decisionism. The latter, a concept taken from Carl Schmitt, is crucial: it justifies a strong executive power centralized in a leader who can act outside norms to defend a community perceived as under threat. This ideology presents itself as the true defender of the “real” democracy of the people, arguing that liberal institutions (independent judiciary, free press, minority rights) have been hijacked by globalist elites and minority groups.

To implement this project, illiberal leaders employ a gradualist and legalistic method, often known as autocratic legalism or democratic backsliding. Instead of carrying out a coup, they use their initial electoral mandate to slowly rewrite the rules of the game:

· Constitutional and legal manipulation: They reform constitutions and pass “cardinal laws” to concentrate power, as Viktor Orbán did in Hungary after obtaining a supermajority.

· Capture of oversight institutions: They hollow out the independence of the judiciary, electoral bodies, and public media, replacing officials with loyalists.

· Siege of civil society and the press: They stigmatize and financially restrict NGOs, especially human rights organizations, and foster a hostile media environment for critical journalism.

The ultimate objective is not to abolish elections but to drain the system of competitive substance, creating a “non-liberal democracy” in which the governing party holds an overwhelming and permanent advantage, relegating the opposition to irrelevance.

The contemporary breeding ground: Discontent, generations, and global crises

The illiberal project does not flourish in a vacuum. It finds fertile ground in a global context of multifaceted malaise, where the promise of liberal globalization no longer convinces broad sectors.

A central factor is the profound disillusionment of entire generations. Generation Z, both in the Global North and the Global South, inherits a world of economic precarity, an unaddressed climate crisis, and deep distrust in institutions. In the Global South, this discontent manifests in mass protests against corruption, lack of opportunities, and disconnected governments, often using digital tools for horizontal organization. In the Global North, such as the United States, this disillusionment frequently translates into electoral apathy or volatile support for disruptive options, fueled by the perception that the system is incapable of solving fundamental problems.

This malaise is exacerbated by converging crises: post-pandemic economic instability, inflation, wars, and forced migration. In this climate of anxiety and insecurity, illiberal discourse offers a powerful and simple narrative: it identifies an enemy (the corrupt elite, immigrants, “aggressive” minorities) and promises to restore order, national sovereignty, and traditional values through strong leadership.

Data confirms the seriousness of the trend. Recent reports show that civic space is closing drastically around the world, with rising arrests of protesters and journalists and the use of repressive laws to silence dissent. This backsliding is affecting consolidated democracies as well, including the United States, France, and Germany.

Paradigmatic cases and projection of the model

The Hungarian model under Viktor Orbán is considered the archetype of illiberal democracy in Europe. Orbán has methodically built a “non-liberal state,” controlling the media, the judiciary, and rewriting the constitution while continuing to win periodic elections. His success has served as a beacon and manual for far-right movements worldwide.

This pattern is repeated with variations. In Latin America, bolsonarismo in Brazil demonstrated the strength of an illiberal movement that, although it lost the presidency, embedded itself deeply in Congress and social structures, constantly challenging institutions, and is thus now imprisoned. The situation in Peru, with its persistent political crisis and youth protests, reflects the collapse of the traditional political center and the search for radical alternatives.

The case of Chile fits within this logic. A potential victory for a candidate promising “order” while evoking an authoritarian past—amid widespread disillusionment with the political class—would be a textbook example of how discontent with the flaws of liberal democracy can be channeled, through elections, toward an option that promises to strengthen executive power at the expense of liberal checks and balances.

A historical crossroads

The relationship between the end of the Cold War and the rise of illiberal democracies is one of profound historical causality. Western hegemony, lacking an ideological counterweight, became complacent, overestimated the strength of its model, and underestimated the contradictions generated by its global order. The “end of history” gave way to the history of disillusionment.

Illiberal democracy is the political form that emerges from this disillusionment. It does not represent a return to the totalitarianism of the twentieth century, but an adaptive mutation of authoritarianism for the twenty-first century: it uses formal liberties to destroy liberal substance, uses legalism to undermine the rule of law, and exploits legitimate discontent to impose an exclusionary form of power.

We stand at a crossroads. The response cannot be nostalgia for an irrecoverable unipolar order nor resignation before illiberalism. Defending liberal democracy requires urgently reconnecting procedural legitimacy (elections) with substantive legitimacy: the capacity to guarantee social justice, ecological security, a dignified life for the majority, and above all, authentic representation within a participatory dynamic between society and power. Otherwise, the exhaustion with a system perceived as corrupted will continue to fuel those seeking to empty it of its emancipatory content.