by George Banez

The five-course lunch typical of Chinese restaurant fare in Manila foreshadowed the meals I scraped by the next ten days. My sister treated me to a send-off lunch before dropping me off at the airport that day. I had to catch the only flight to Puerto Princesa, the capital city of Palawan Island where I would study forests.

Served family-style on a Lazy Susan turntable, classic Filipino Chinese food drew inspiration from culinary traditions different from the sweet, sticky-sauced American Chinese take-out. Each course highlighted one main ingredient, and it was seasoned just enough to bring out natural flavors.

Unless instructed otherwise, servers delivered fried rice last. That ensured diners got to progressively fill up on the cold cuts starter, soup, fish or seafood, vegetable, meat, and noodle dishes.

Lunch was nothing to complain about. But I could not eat much. I felt anxious. It was my first trip to Palawan, the fifth-largest island in the Philippines. Back in 1990, two-thirds of it were still covered with thick forests. Located on the western edge of the country with 7,641 islands, Palawan had just been declared a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve.

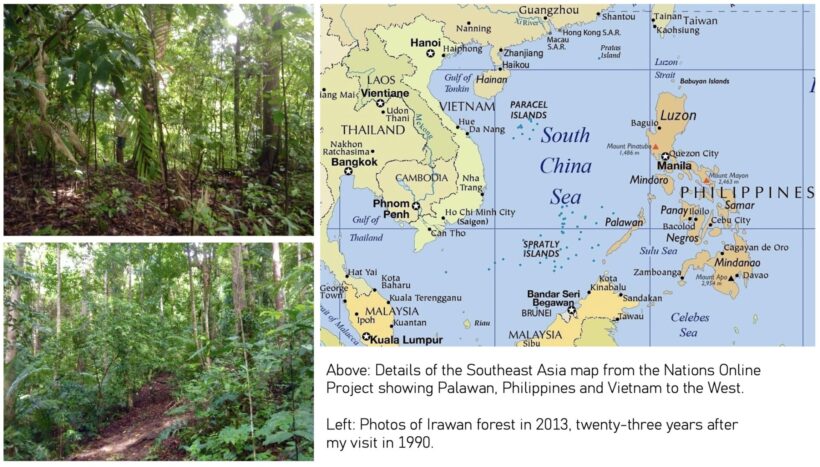

Long and narrow, around 450 km (280 miles) in length, the main island itself is surrounded by 1,780 smaller islands. Palawan lies west of the vast inland Sulu Sea. Its west coast hem the Philippine Sea that connects to the South China Sea. Across these international waters is Vietnam.

Palawan Island sits on the extension of the Sunda Shelf, the submerged continental shelf of Sundaland. Even today, the exposed landmasses on Sundaland –the Malay Peninsula, the islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo– are rich in biodiversity. The plants and animals there are varied and highly endemic, found nowhere else but in their locale or that region. Palawan also had unique flora and fauna. So, the task ahead was daunting.

No Turning Back

At lunch, I thought about the assignment: survey tree species on a hectare (2.47 acres) plot of the tropical forest of Irawan, Puerto Princesa. Then in 1990, I urgently needed to complete the master’s degree I started six years earlier. By some twist of fate, I graduated from the university at the age of 20. But interruptions slowed down graduate school. I was nearing the maximum time allowed to finish a master’s degree in biology.

I immediately agreed to work on the plot set up by Drs. Domingo Madulid and Djaja D. Soejarto in Irawan. Harvard-trained botanist Soejarto was tasked by the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) to find anti-cancer phytochemicals from trees worldwide. I committed to collecting data from the plot without having set foot in Palawan.

Today, Irawan is considered a “barangay,” the smallest administrative or political unit in the Philippines. But back in 1990, Irawan’s 4,766 hectares (11,777 acres) of forest was designated as the city’s watershed. It extended from the western shores of the narrow Puerto Princesa Bay to the middle of the island. Declared part of the Iwahig Penal Colony, a 34,000 hectare (84,016 acre) fenceless prison, its forest served as natural barrier to deter jailbreak.

Confident that I Knew Forests Well

At that time, I headed the Philippine Uplands Resource Center (PURC), a clearinghouse on forestlands. We provided information support to organizations working to reforest and restore uplands to sustain the communities that depended on them. As an instructor, I took students on educational trips to forests near Manila. Before that, I had written learning modules on forest conservation.

But I had no mental image of Irawan or the assignment’s magnitude. Not knowing enough may have worked in my favor. Otherwise, I might have declined. When I met Dr. Madulid for a briefing before the trip, he handed me a piece of paper with a name, Rey Majaducon, and his address –Irawan Flora, Fauna, and Watershed Reserve (IFFWR). That was it.

Less than 30 of us passengers on the airbus landed in Puerto Princesa that afternoon. On Palawan’s east coast, the tiny airport sat on its seaward edge to Sulu Sea. From there, I went to Duchess Inn by “tricycle-taxi,” the only means of public transportation. A motorcycle with a passenger side car was still the primary way of getting around the city when I came back in 2013.

Just 13 km (8 mi) from the city center, Irawan in 1990 was only accessible by the tricycle. On the way there, I barely saw houses or humans. Both sides of the paved Puerto Princesa South Road were green with trees. I heard then that any man wearing a wide-brim hat walking solo was likely a “resident” of Iwahig.

Back then, the landmark to turn right onto the dirt road to Irawan was also the only concrete structure visible roadside, the “Crocodile Farm.” Later renamed “Palawan Wildlife and Rescue Center,” the structure was impossible to spot among the sea of houses in 2013.

From the turn, IFFWR’s office-staff house stood another 1.7 km (1mi) away. The tricycle driver took me there to find Rey Majaducon. But he had already gone planting trees, so I waited while an elder man, Tatang, fetched him.

Saved by the Kindness of Strangers

Majaducon, who would later guide me to the plot, also became my field assistant. When we met, he said that I needed to buy supplies. Aside from paint for marking trees and ropes to create a grid or subplots, I had to get food and water to last me a week. And I could only get them in the city.

Since it took over an hour from the staff house to the plot at around 300 m (984 ft) elevation, Majaducon asked if I wanted to camp out or climb up and down daily. Either way would require food provisions and packed lunch. So, I took Majaducon with me to the city and sent him grocery shopping while I went to get supplies.

Lucky for me, I recognized the owner of the hardware store. He was a former student’s boyfriend who came to pick up his then girlfriend after class. Together with his now wife, they worked the family business in Puerto Princesa. He strongly advised against camping. And after giving me a worried look, he jokingly compared my assignment to Harrison Ford’s movie adventures. Then he became serious. Like the owner of the Duchess Inn guesthouse, he said I should eat well to keep malaria away.

At that time, I knew nothing about feeding myself. I relied on the kindness of my mother’s helpers to prepare me food. So, I requested Majaducon’s wife to cook and pack us lunch daily. Then I asked the resident crew to let me join their meals with the groceries I bought.

Meanwhile, Majaducon got us rice and what would go with it. That meant canned sardines, luncheon meat, and dried fish –food that would not spoil. As the staff house did not have a refrigerator or electricity, I could not be picky. But I was unprepared for the monotony.

Back then, I was also oblivious of the Filipino practice of communal eating, where everyone was invited to partake and the person with means covered the costs. I survived only because Majaducon helped me adjust accordingly.

More Surprises

Duchess Inn was one of the only two guesthouses in the city in 1990. It was a two-story wooden house converted into what today would be an AirBnB. To my surprise, they served me the best baguette-like bread with two eggs for breakfast.

The staff told me that a Vietnamese baker made the crispy and airy bread. They explained that near the airport was the Vietnamese Refugee Processing Center (VRPC). It was established as the Philippine First Asylum Camp (PFAC) in 1979 by the government with support from the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Meant to help the Vietnamese fleeing by boat after Saigon fell in 1975, the camp was temporary shelter for those waiting to be resettled in the U.S., Canada, or Australia.

I stopped by VRPC on my way to the airport. There, I saw not only desperation but also the resilience of a thriving community. Arrivals had slowed down from their peak in the mid-80s. But asylum seekers stayed longer due to delays in third-country resettlement. So, around 10,000 refugees lived there then.

Eleven years after VRPC opened in 1979, the camp was its own township until it closed in 1996. It had restaurants, stores, clinics, and places of worship. Because it was an open camp, integration with locals was possible. Visitors to Palawan like me benefited from displaced Vietnamese bakers’ skills.

Looking back now with more experienced eyes, I wonder how half a million refugees who passed through the camp from 1979 to 1995 survived. Surely a kinder world back then provided them rice and whatever went with the staple, perhaps canned food and fish.

About the Author:

George Banez is a writer of Filipino descent and is a retired non-profit professional living in Florida.