Ban on mercury in dental fillings is a positive step. But small-scale gold mining will remain the largest global contributor to mercury pollution without urgent action.

07 November 2025. Geneva. Despite the growing crisis of mercury contamination in the Amazon, Africa and parts of Asia caused by mercury use in small-scale gold mining (also called artisanal and small-scale gold mining, ASGM), at the Sixth Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention this week, delegates failed to take strong action toward amending the Convention to ban this use of mercury. The concerns are especially urgent in Latin America, where food sources of Indigenous Peoples are widely contaminated by mercury from ASGM. A recent IPEN study of women in Indigenous communities in Peru and Nicaragua found that nearly all women had a mercury body burden that exceeded safe limits by several fold.

In a positive note, following a decade-long effort by the World Alliance for Mercury-Free Dentistry and supported by many IPEN members, delegates agreed to phase out mercury in dental fillings by 2034. But the Convention’s articles to control mercury use in small-scale mining remain weak and rely on the slow development and implementation of government National Action Plans. Organised crime, corrupt officials, police and military, and armed factions controlling gold mines exploit this weakness, and mercury continues to pour into the gold mining areas. The growing crisis has been exacerbated by skyrocketing gold prices that are fuelling the most tremendous gold rush of modern times.

IPEN Co-Chair, Goldman Prize Winner, and ASGM expert Yuyun Ismawati said, “It is concerning that the worst mercury poisoning tragedy 70 years ago in one country is now seen in more than 60 countries, with the latest gold rush. To make mercury history, strong commitments from Parties are needed. The amendments to the Convention should start by prohibiting the use of mercury for ASGM, closing cinnabar mining sites, and ending the mercury trade. Eight years after entering into force, the COP should signal a more substantial commitment to prioritise health over gold.”

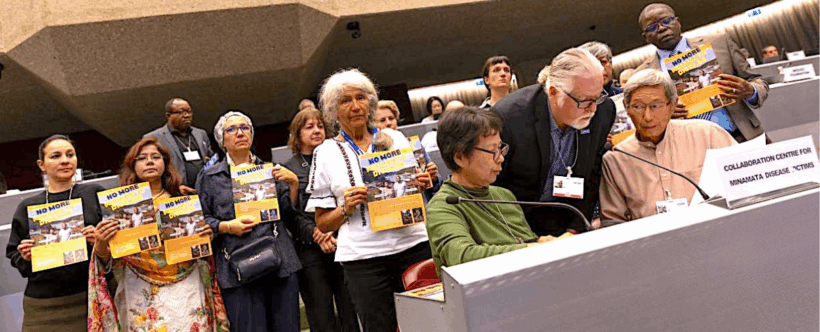

Representatives of indigenous communities in the Amazon spoke out at the COP, demanding action to ban mercury use in gold mining in the region, which is contaminating their primary food source: river fish. The unavoidable consumption of contaminated fish by Indigenous People has led to widespread mercury poisoning among their communities. Previous biomonitoring studies by IPEN and others have shown elevated levels of mercury in the majority of Indigenous Amazonian women who participated.

Mercury is used in ASGM because it binds with gold, allowing the extraction of gold particles from low-grade ores by small-scale miners. The mercury/gold amalgam is then burned, turning the mercury to vapour, leaving behind a small amount of gold. This process results in clouds of toxic mercury vapour, contaminated tailings, and the release of mercury into the environment, with mercury from ASGM being the leading contributor to global mercury pollution. In the Amazon, this results in contamination of the food chain, especially of fish in the massive rivers that traverse the region.

Despite the growing crisis, the only official discussion of the issue at the COP was a proposal to increase accountability and transparency of the gold industry about how it sources gold and to create market opportunities for mercury-free gold. IPEN warns that these small positive steps do not address the core issues of the global mercury trade being mainly diverted to gold mining and remains concerned that mercury use in ASGM is still permitted under the Minamata Convention with no phase-out date. This sends the message that gold production is more important than environmental destruction, mercury food chain contamination, human rights abuses, and health impacts on Indigenous Peoples, women, and children in ASGM regions.

IPEN Technical and Policy Advisor Lee Bell said, “Unfortunately, this week the COP fiddled while Rome burned. Small adjustments were made to relatively minor issues while the COP failed to address the mercury pollution crisis in the Amazon. One after another, Indigenous Peoples delegates addressed the plenary, pleading for help, demanding action to ban mercury in the Amazon, and describing their sorrow and anger at the contamination of their food sources and people, to no avail. At COP-7, we must take decisive action. Parties must show the courage to put forward and support proposals to amend the convention to end the mercury trade, ban mercury mining, and end ASGM as an allowed use of mercury.”

Dr. Marcos Orellana, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Toxics, repeatedly spoke out at the COP on the need to amend the convention to ‘address the gaps’ that allow mercury use in gold mining to continue and grow unchecked. In his 2022 report on mercury in ASGM, Orellana laid out the three amendments of the Convention that are needed to make real inroads into the mercury pollution crisis driven by ASGM:

- End the global trade in mercury.

- Accelerate the phase-out date of primary mercury mining, the source of most mercury, from the current 2032 deadline to 2027.

- Establish a deadline of 2032 to prohibit ASGM as an allowable use of mercury.