It is not fatigue: it is erosion. Reality, when it touches you daily with the coldness of a war report and the smell of a morgue, wears you down from the inside until it makes invisible the edges that once held you up. What broke me was not sleepless nights nor the editorials of others trying to dictate what “balance” should be: it was looking straight, lucidly, at where the world is sinking —as I did for three years in a conflict zone in my own country, from which I brought back this post-traumatic stress disorder— and accepting that my job is to write it down anyway, even when it hurts. There are days when journalistic language is not enough; days when all that’s left is the pulse of my hand on cheap paper, in a psychiatric hospital studio, with poor materials and the dignity of insisting.

As I write this, I think of my colleagues in conflict zones. The toll in Gaza admits no euphemisms: it is the deadliest period for the press since the Committee to Protect Journalists began keeping records, with at least 192 journalists and media workers killed since October 2023 — in Gaza, the West Bank, Israel, and Lebanon. 2024 was the deadliest year for the profession since records began, with 124 killed, almost two-thirds Palestinians killed by Israel, according to CPJ. The exact figures vary by methodology, but Reporters Without Borders also speaks of “almost 200” journalists killed in Gaza and of newsrooms wiped out under a blockade that has lasted for more than eighteen months. There is no metaphor that can soften this. It is what it is: devastation with names and surnames, with cameras, vests, and notebooks among the rubble.

I have spent weeks entering the small hospital studio where I paint. There are no noble oils or acid-free papers; there is what there is: pastels that stain, temperas that crack, papers that absorb poorly and leave the imprint of the place on every layer. The art that comes out of that room is not occupational therapy. It is a declaration of existence. It is the smallest gesture —a line, a shadow— that gives me back agency when language is saturated with numbers and my morality feels like a fatigued muscle.

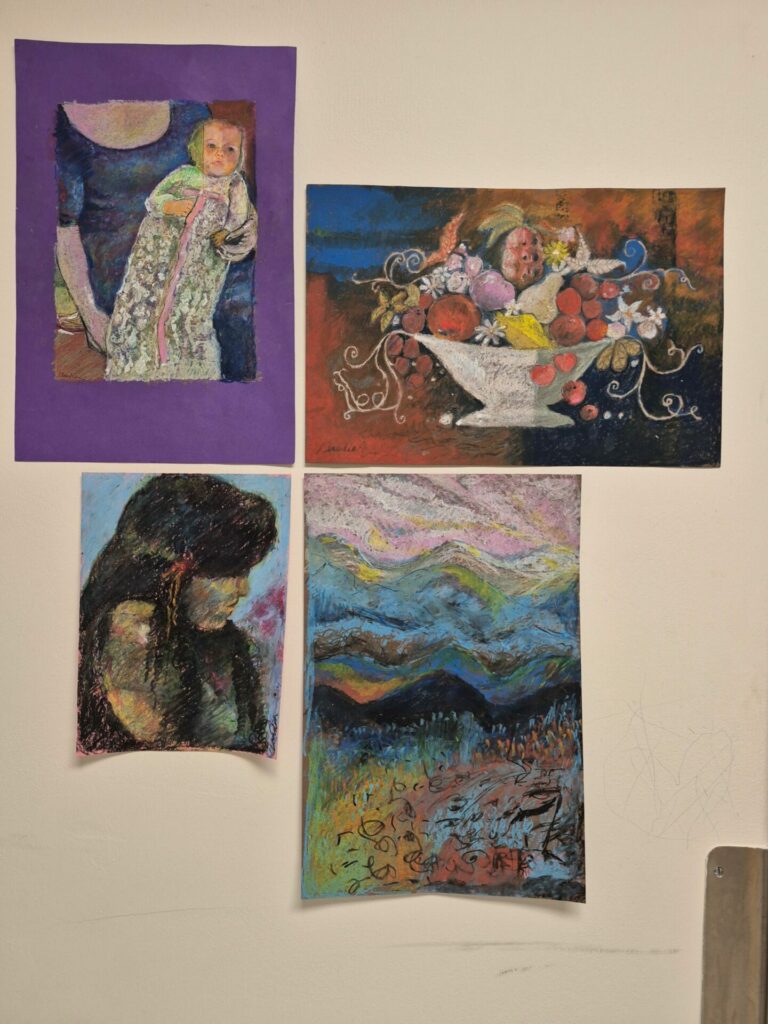

From that pulse came four pieces that now, seen together, are my clinical and ethical map. “Without Gender Identity” opens the intimate diptych: a baby firmly held by a body that is not named. Without the violence of a manifesto, the work questions early labeling, the grammar of signs that society imprints before we even learn to say “I.” “Untitled Still Life” looks like a pause, but it is not: traditional abundance is under suspicion in a hospital. Beauty, in certain contexts, can be a façade or a taxidermy of memory. “I Miss You, Mom” is the body leaning toward an unseen hollow: grief, longing, the memory of care as an open wound. And “The World Falls from the Steppe” shifts the scale: a convulsed landscape, a horizon interrupted by strokes that refuse to negotiate calm. The poor materials here do not get in the way: they speak. Pigment that does not fully cover lets the fissure show; the fissure is the message.

I think of my colleagues in Gaza: working in the open air of censorship, with foreign access restricted and the impossible burden of narrating for the world while the world collapses around you. The accounting is obscene but necessary: CPJ and RSF do not report trends; they document deaths, destroyed newsrooms, annihilated families. Let us not forget: journalists are civilians under international humanitarian law. There is no “acceptable collateral damage” when the target is the voice that bears witness. And yet, we go on. Because everyone knows, everyone shouts, everyone demands; the truth, even dismembered into a thousand pieces, reassembles itself from the remains.

The psychological cost is not a romantic subject. It is studied to the point of coldness: the greater the exposure to traumatic events, the greater the severity of symptoms. There’s no need to translate it into jargon to understand it; it’s enough to remember the last time you couldn’t sleep after editing a video you didn’t want to see. Conscious journalism is not a pose; it is accepting that the body pays for lucidity. And even so, self-care is part of the job: boundaries, honest conversations with editors, protocols so that covering violence does not consume us (nor our sources). That these exist in guidelines does not mean they are fulfilled, but denying their urgency would be a betrayal.

In the psychiatric hospital I understood something else: precariousness is also a language. When the material fails, you invent structure with the caress of a stroke, you correct with the reverse of the paper, you build volume from what seemed like a mistake. That obstinacy is the same one that allows us to write under informational bombardment, to hold on to rigor while everything around us pushes toward confusion. Art —there, with its minimal means— gave me a mirror in which to recognize myself without the armor of data. Not as an escape; as proof.

To my colleagues in war zones I owe not an elegy, but a non-negotiable solidarity. There will be no forgiveness for those who think that killing journalists is killing the truth: they did not kill it. The truth, damn it, seeped through every piece of rubble, every name, every number someone verified by hand, at dawn, with their heart in their throat. That is what “The World Falls from the Steppe” is about: the collapse that cannot swallow the voice. And that is also what this text is about: the price of looking without blinking, the clumsiness with which the body tries to go on, the humble rescue offered by a cheap sheet in a hospital studio.

History always collects. There is no accounting that exempts it. When the bill comes —because it will come— may it find us with our archives in order, our pieces hung, our signatures visible, and our conscience intact. In the meantime, we will go on writing, painting, breathing: stubborn, lucid, alive.