By Maxine Lowy

An honor granted by the president of a democracy to the dictator of a neighboring country offers clues for understanding the background of a military intelligence orchestration from 50 years

ago, known as Operation Colombo or the List of the 119.

At the end of February 1975, María Estela Martínez de Perón, President of the Argentine Republic, awarded the Order of May for Military Merit to Augusto Pinochet.

In the 18 months following the civil-military coup led by Pinochet, more than 1,600 people had been extrajudicially executed or disappeared after being kidnapped; thousands more were

arbitrarily detained in prisons, some official, others clandestine. The Argentine president praised the Chilean dictator at the same time as she began to emulate in her own country the same

practices already condemned by the United Nations in November of the previous year.

On February 5, three weeks before her recognition of the Chilean dictator, President Martínez de Perón signed Decree 261/75, which gave the Army the green light to “neutralize and/or

annihilate the actions of subversive elements” in Tucumán, a province in the northeast of the country. In less than a week, 1,500 soldiers under the command of General Adel Vilas were

deployed to the southern part of the province.

Throughout 1974, federal police offensives had intensified against the insurgency of the Ramón Rosa Jiménez Mountain Company, in a province undergoing social unrest due to the massive

closure of sugar mills and the loss of its economic base. The history of the people of Tucumán, with a strong labor tradition, has demonstrated their resistance to injustice and the precariousness of life. Now, the Workers’ Revolutionary Party (PRT), with the Compañía de Monte under its wing, was the declared enemy. Any community, union, or person could be taken from the street, their home, school, or workplace, accused of being subversive and subjected to unimaginable treatment.

Thus began what the military called Operation Independence, and with it, the systematic introduction of forced disappearance and clandestine detention centers. During the year 1975,

prior to the coup, 175 persons were forcibly disappeared and 37 persons were directly murdered.

There was still a high probability that a person who was abducted would survive, to which 406 people can attest (A. S. Jemio, from EASQ/OCE data base). 2

In Tucumán, a new mode of production of state violence” was being refined, as sociologist Jemio put it, which would soon spread throughout the country. In this context, Argentina offered fertile ground and a willing ally for Chile’s goal of denying the existence of forced disappearances on its own soil.

Chile and Argentina had been closely collaborating long before.

Argentine agents of the Triple A paramilitary group had played a decisive role in the logistics that facilitated the assassination in Buenos Aires of former constitutional commander Carlos

Prats and his wife Sofía Cuthbert, six months earlier.

On April 18, 1975, Pinochet arrived at Morón Air Base — the same place where he had met with then-President Juan Domingo Perón in May the previous year — to seal the bond, anticipating

the formalization of Operation Condor in November, five months before the coup in Argentina.

Addressing President Martínez de Perón, Pinochet said: “This fraternal union, madam, born in the principles of our republics… was forged in the blood of Chilean and Argentine men on the

battlefield. … I am sure that this meeting with you, madam… will undoubtedly be a moment that will bear fruit for this old friendship.” 3

Operation Colombo was one of the “fruits” of that camaraderie. Centered on a media campaign driven by journalists loyal to the Chilean dictatorship, the Chilean press began laying the

groundwork with references to the guerrilla conflict in Tucumán. In February the daily La Segunda featured headlines such as, “Army intervenes in anti-guerrilla fight in Tucumán,”

(2/10/1975) and “Guerrilla ambush in Tucumán, (2/19/1975).

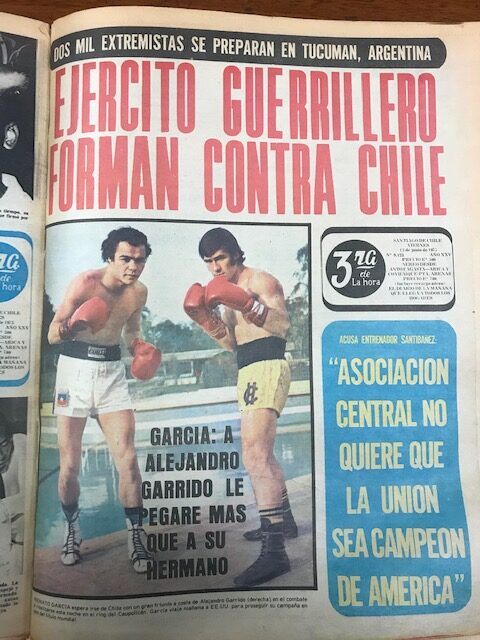

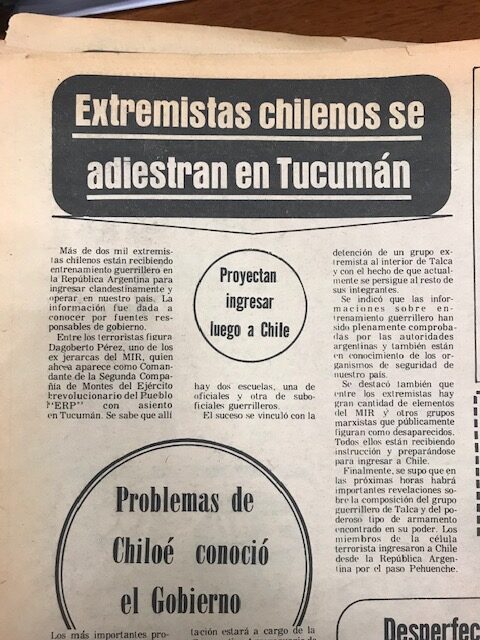

On June 13, the newspaper La Tercera de la Hora published the first reference to Chileans being present in Tucumán. The headline read: “Two thousand extremists are training in Tucumán,

Argentina.”

La Tercera de la Hora

La Tercera de la Hora

The scene described in the report was not only a blatant lie but also absurd. According to historian Gonzalo Getselteris, author of an exhaustive study on the Compañía de Monte Ramón

Rosa Jiménez, in May 1975 the guerrillas numbered no more than 100. 4 The idea that there were hundreds of fighters was “a myth that worked against them,” provoking a disproportionate

military response. In any case, it would have been impossible to supply and shelter a large group in the humble shacks of the area — even less in the mobile camp in the forest.

Why couldn’t there have been a couple thousand Chileans in Tucumán?

First, the historian notes that in this small province, with its distinctive tone and rhythm of speech, it would have been impossible for a contingent of Chileans to go unnoticed. Second,

since 1974, and more intensely in 1975, police and military were stationed at checkpoints at bus terminals, the train station, and along major roads. Hundreds of foreigners could not have slipped through undetected, he notes.

Nevertheless, the fiction contained a tiny speck of truth.

After fleeing across snow-covered volcanic slopes and through the Valdivian forest, pursued by the military, MIR (Movement of the Revolutionary Left) members Domingo Villalobos Campos

and Svante Grande, originally from Sweden, met again in the hills of Tucumán in late 1974.

They probably reunited with two or three other comrades also from Neltume. Their presence in Tucumán was the result of an agreement between MIR and the PRT (Workers’ Revolutionary Party) leadership. Domingo Villalobos Campos died on May 29, 1975, in a confrontation in Manchalá. Svante Grande was killed in action on October 14, 1975.

Two weeks after the Manchalá incident, La Tercera de la Hora published its report. The article provides evidence of communication between Chile and the Argentine military in Tucumán. The second paragraph reveals either a case of faulty intelligence or deliberate fake news: “Among the terrorists is Dagoberto Pérez, one of the former MIR leaders, who now appears as

Commander of the Second Mountain Company of the People’s Revolutionary Army…”

At the time, Dagoberto Pérez was still part of MIR’s clandestine leadership and would remain alive until October 16 of that year, when he was killed in Malloco, Chile, in a confrontation with

state agents. The man who died in Manchalá was Sergeant “Dago” — the alias of Domingo Villalobos Campos in Argentina — who was indeed in charge of the Second Company during a

failed mission to reach the headquarters of Operation Independence. Eleven conscript soldiers also died.

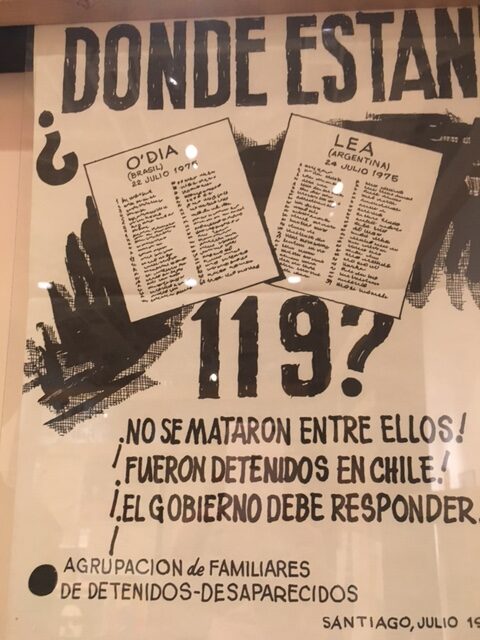

The analysis of this article is just a glimpse — the tip of the iceberg — revealing the entirely false nature of the media campaign that formed the core of Operation Colombo. In mid- and late

July, this campaign claimed that 119 Chileans had died in Salta and Tucumán, Argentina. For those who devised the scheme, a handful of internationalist Chileans in Tucumán sufficed to

construct the scaffolding of the conspiracy.

The scaffolding turned out to be so weak that it collapsed.

Upon recognizing in newspapers the names of people with whom they had been imprisoned in clandestine jails, 90 political prisoners at the Puchuncaví detention camp declared a hunger

strike. Their outrage upon realizing that the dictatorship was killing their comrades overcame their fear. Many years later, Juan Guzmán Tapia (1939–2021), former judge of the Santiago

Court of Appeals, was the first to prosecute Augusto Pinochet for Operation Colombo, and commented that for him, it was the “easiest case” to prove.

Another clumsy fabrication involved four scorched bodies found in Buenos Aires, in April and July, with fake IDs and signs allegedly linking the brutal murders to MIR. This forced the

families of civil engineer David Silberman, architect Luis Guendelman, sociologist Jaime Robotham, and chemical engineer Juan Carlos Perelman to travel to Buenos Aires to inspect the

corpses. The four did not know each other, they were members of different political parties and they were last seen alive at different detention centers. The family members quickly dismissed

the claim — it was clear these bodies were not of their loved ones, who had been detained in Chile and whose whereabouts they had been desperately searching for months.

If not, then who were they? Who’s still looking for them? Who were the perpetrators? These are still unanswered questions, uniting Argentines and Chileans 50 years after Operation Colombo, the same 50 years since the beginning of forced disappearances in Tucumán.

Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos (M. Lowy, 2024)

2 Ana Sofía Jemio, Tras las Huellas del Terror: El Operativo Independencia y el comienzo del genocidio en Argentina, Buenos Aires (Prometeo Libros, 2021), p. 256.

3 Source: https://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/29610)

4 Gonzalo Getselteris, Desde el monte. La Compañía de Monte vencerá, Lanús (Buenos Aires: 2015). Nuestra

América.