In just two weeks, Médecins Sans Frontières reported that 167 people were treated for severe injuries caused by drone attacks in civilian areas of Sudan. Penetrating chest wounds, fractured skulls, amputations of children. What the medical report describes in clinical terms exposes something deeper: the consolidation of a technological form of warfare operating over civilian populations in a conflict relegated from the international agenda.

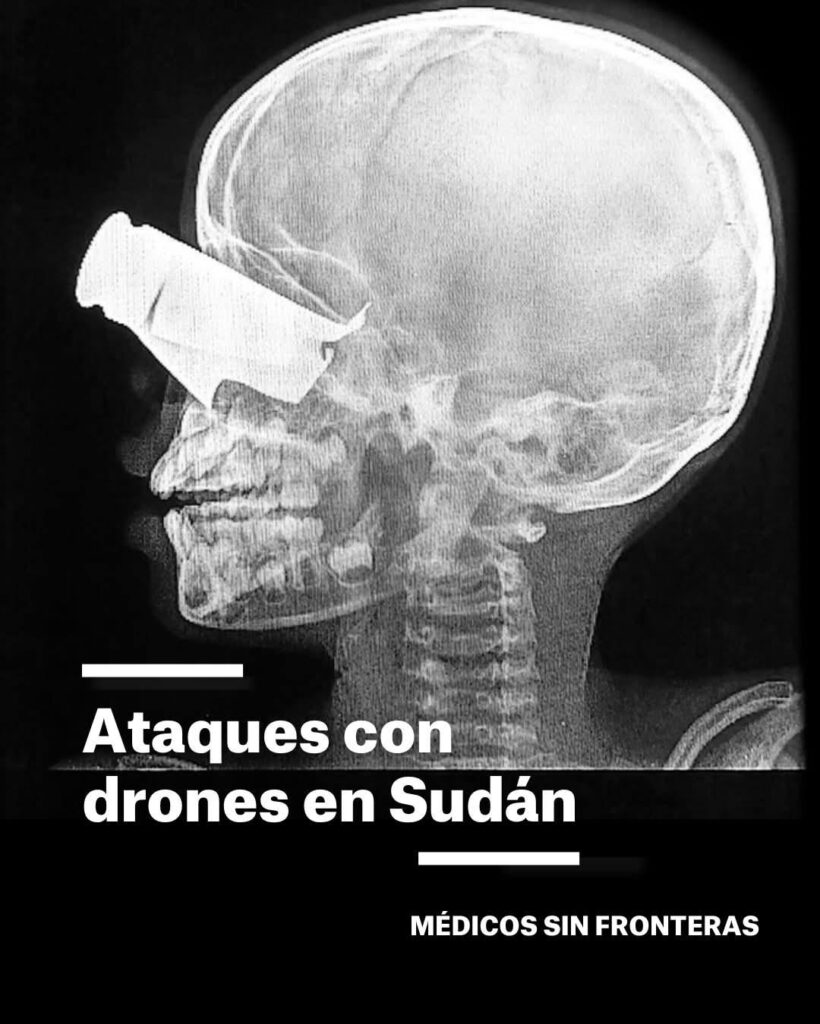

In Sudan, the figure is neither minor nor isolated. Médecins Sans Frontières documented that its teams treated 167 severely injured patients within a two-week period, with injuries consistent with munitions dropped by drones in civilian zones. The descriptions leave little room for ambiguity: penetrating wounds to the chest and abdomen, traumatic brain injuries, multiple fractures, amputations. Among the cases, a nine-year-old child with shrapnel in the eye, extensive facial fractures, and two amputated fingers, transferred to N’Djamena for specialized surgery, with a high probability of permanent disability.

The communiqué is not a political declaration. It is an expanded clinical report. Precisely for that reason, its weight is greater.

Since April 2023, Sudan has been engulfed in open warfare between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces. What began as a struggle for control of the state apparatus has evolved into a prolonged urban conflict, mass displacement, and the collapse of the health system. In recent months, several organizations have pointed to an escalation in the use of armed drones in densely populated areas.

Human Rights Watch has warned of indiscriminate attacks in residential neighborhoods and the use of explosive weapons in urban environments. Amnesty International has denounced impacts on civilian and medical infrastructure. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights has reiterated that the principles of distinction and proportionality are binding legal obligations under the Geneva Conventions. The International Committee of the Red Cross has insisted that hospitals and medical personnel must be protected at all times.

The pattern described by these organizations converges with the medical report: explosions in civilian areas, victims with shrapnel injuries, and an overwhelmed health infrastructure.

The use of drones introduces a specific dimension. These systems allow attacks to be carried out without exposing one’s own troops, reducing internal political costs and enabling operations at a distance. In contemporary military discourse, they are presented as instruments of precision. However, when the recurring result is injured children, amputations, and traumatic brain injuries in residential neighborhoods, precision ceases to be a technical attribute and becomes a legal question.

International humanitarian law requires a distinction between military objectives and civilians. It also prohibits attacks that are disproportionate in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated. When impacts are recorded in civilian areas and the injured are counted in dozens over short periods, the obligation is not only moral but investigative. It becomes necessary to determine whether there is a pattern, intent, or systematic negligence.

Sudan has become a space where military technology operates with low international visibility. Unlike other conflicts, media coverage is intermittent. Diplomatic attention is fragmented. Political pressure is limited. That combination creates fertile ground for the normalization of practices that, in other geopolitically prioritized contexts, would provoke more forceful responses.

The case of the child transferred to N’Djamena encapsulates the structural dimension of the conflict. The child was not only wounded by shrapnel; he had to endure extreme conditions to access specialized surgery outside the country. The Sudanese health system, weakened by years of instability and aggravated by war, cannot absorb the volume or severity of such cases.

When an urgent medical communiqué becomes the primary source of information about the technological escalation of a war, the signal is clear: the humanitarian record is substituting for the political record. Medical and human rights organizations are documenting what should be subject to robust international investigative mechanisms.

The statement that “civilians must always be protected” is not rhetorical. It is the cornerstone of the international legal order established after the Second World War. If that principle erodes in peripheral conflicts without visible diplomatic or judicial consequences, the system as a whole weakens.

Sudan is not merely a prolonged internal conflict. It is also a mirror of contemporary warfare: outsourced, technologized, executed at a distance, and ultimately borne by civilian bodies.

The urgent communiqué of Médecins Sans Frontières is not just another entry in the chronology of the conflict. It is a clinical diagnosis of a war advancing with drones over neighborhoods where the distinction between combatant and wounded child appears, in practice, to have blurred. And as long as the international response remains fragmented, the medical report will continue to be the most precise document describing the anatomy of this violence.