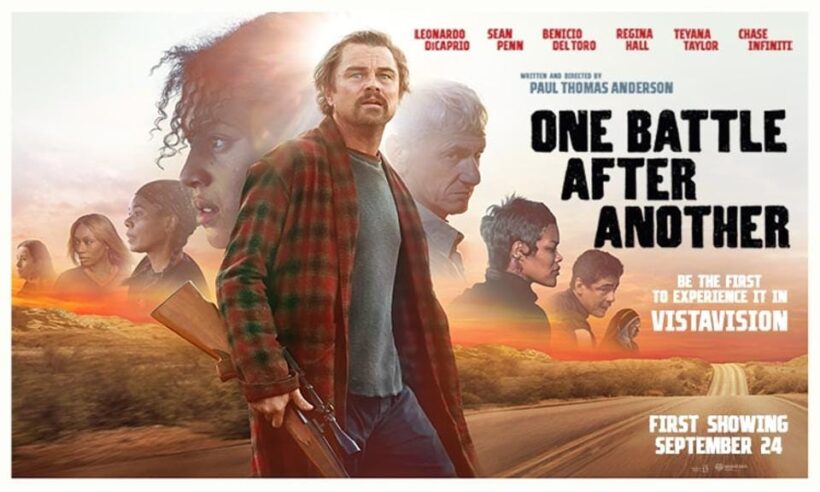

We live in an age that prides itself on vigilance. We are told—often correctly—that history never ends, that reaction never sleeps, that injustice returns in new guises the moment we look away. The lesson appears sober, even responsible: there will always be another battle. And so we prepare ourselves for endurance rather than transformation. Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (2025) stages this lesson with admirable seriousness. It offers no triumphalism, no illusion of final victory. Fascism, authoritarianism, reaction—call it what you will—returns again and again. The struggle is permanent.

But permanence is not neutrality. To insist that struggle never ends is already to take a position about what kind of politics is possible—and what kind is not. When we place One Battle After Another alongside two of the most influential contemporary political philosophers, Slavoj Žižek and Alain Badiou, something sharper comes into view. What looks like realism begins to resemble consolation. This article argues that both Žižek and Badiou help us see why the mantra of endless struggle, however militant it sounds, may function as a subtle form of reassurance—one that protects us from the far more unsettling question of whether a different political horizon is possible at all.

We usually think of consolation as gentle or sentimental: holiday movies, narratives of personal redemption, assurances that things will work out. But consolation can be severe. It can come clothed in realism, cynicism, even militancy. To be told “there will always be another battle” can feel bracing, adult, unsparing. It denies false hope. It rejects naïve optimism. Yet it also does something else: it normalizes repetition. It teaches us to expect recurrence rather than rupture, management rather than transformation. This is the deeper target of my critique: not hope, but endurance elevated into virtue. Consolation today no longer says “everything will be fine.” Instead it says, “Nothing will ever be fine—but that’s just the way things are.”

A Žižekian reading of One Battle After Another begins from suspicion. Žižek’s central claim, repeated across decades, is that ideology today rarely takes the form of deception. We often know very well how bad things are. Ideology works instead by shaping what we take to be inevitable. From this perspective, the film’s insistence on endless struggle is not merely descriptive; it is ideological. It teaches us to experience repetition as realism. The enemy’s perpetual return becomes proof that no fundamental change is possible—only vigilance, resilience, and renewal.

Žižek would focus on the film’s libidinal economy: the strange enjoyment embedded in resistance itself. The characters are exhausted, traumatized, and cynical, yet they are also animated by the struggle. Their identities are inseparable from opposition. Fighting is not merely a duty; it is a source of meaning. Here Žižek introduces one of his most unsettling ideas: jouissance, or enjoyment. We do not merely suffer ideology; we participate in it because it offers satisfaction. Endless struggle allows us to feel morally righteous without risking the destabilization that real change would demand. We remain engaged, critical, vigilant—while the basic coordinates of the system remain intact.

In this light, One Battle After Another risks becoming a lesson in pseudo-activity: constant motion that leaves the structure untouched. Resistance becomes a ritual rather than a rupture. We fight not to transform the world, but to reassure ourselves that we are not complicit. The consolation here is harsh but real: you will never win, but you will always be needed. That promise is strangely comforting.

One sees a more explosive version of this dynamic in Romain Gavras’s Athena (2022), which stages insurrection in the Paris banlieues with breathtaking, almost ecstatic intensity. The camera moves with the rioters; anger becomes choreography, fire becomes illumination. The uprising feels urgent, righteous, alive. And yet there is a strange surplus in it—an energy that seems to feed on its own momentum. The revolt does not merely express outrage; it generates meaning, belonging, even exhilaration. The struggle binds the brothers together more securely than any victory could. By the end, the spectacle has burned bright—but the structure that produced it stands. The riot has given identity without delivering transformation.

The film captures the intensity of decision with extraordinary formal fidelity; what it does not show is a redefinition of the situation itself. The revolt is spectacular, but it is not an Event. If Žižek exposes the satisfaction hidden within revolt, Badiou asks a harder question: what, if anything, has actually changed? Where Žižek begins with suspicion, Badiou begins with possibility. His philosophy is organized around a single, demanding idea: the Event. An Event is not a large happening or a dramatic spectacle. It is something that breaks with the existing order in a way the order itself cannot explain. For Badiou, politics is not endless resistance. It is rare, difficult, and discontinuous. It begins when something previously unthinkable appears—and when subjects commit themselves to it through fidelity.

From a Badiouian perspective, One Battle After Another does not merely risk ideological repetition; it fails to stage politics at all. There is struggle, courage, sacrifice—but no Event. Nothing happens that redefines the situation’s coordinates. The enemy returns because nothing has interrupted the logic that produces it. Badiou would not be impressed by the film’s realism. He would call it capitulation to the situation. By insisting that the battle never ends, the film forecloses the possibility that something genuinely new might occur. Perseverance is mistaken for fidelity. Endurance replaces truth. Here the consolation takes a different form. We are spared the demand of commitment to an Event that might fail, isolate us, or require abandoning familiar identities. Instead, we are offered the safety of continuity: one battle after another, with no decisive wager.

Žižek and Badiou disagree profoundly. One emphasizes ideology and enjoyment; the other truth and rupture. Yet in this case, their critiques converge. Both would recognize in One Battle After Another a refusal of the most difficult political question: What would it mean for the struggle to end—not in defeat, but in transformation? For Žižek, endless resistance risks becoming an ideological supplement to the status quo. For Badiou, it marks the absence of an Event worthy of fidelity. In different languages, both are saying the same thing: repetition has been mistaken for seriousness. This convergence illuminates the deeper problem with contemporary political culture. We have learned to distrust hope, to treat utopianism as naïveté, and to mistake pessimism for maturity. But what if pessimism has become the most seductive consolation of all?

The most dangerous consolation today is not optimism but moral vigilance. We take comfort in our awareness, our alertness, our refusal to be fooled. We know the enemy never disappears, that the struggle is endless, that history offers no guarantees. But knowledge can also function as anesthesia. It can prevent us from asking whether our political imagination has been quietly disciplined into submission.

One Battle After Another does not lie to us; it tells the truth about recurrence. But it also teaches us what not to desire: an end to the battle that would require rethinking the world itself. Repetition is seductive because it keeps us ethically mobilized without risking rupture. We suffer, we endure, and we call that politics. But endurance is not moral adequacy. Suffering does not justify itself. Vigilance is not transformation. When resistance is severed from the possibility of change, it becomes ritual. The satisfaction lies not in victory, but in having once again stood on the correct side of the struggle.

There are, however, films that refuse this consolation altogether. Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men (2006) does not reassure us that the battle continues, nor does it flatter us with vigilance. It stages a world in which struggle itself has become exhausted—where resistance movements are hollow, politics is reduced to containment, and hope is no longer a usable category. And yet action remains possible. Theo does not act because he believes in the future, or because history demands it, or because endurance has become virtue. He acts without reassurance. Responsibility here is not sustained by repetition, but by exposure to a singular demand that offers no promise in return. This is what non-consolatory ethics looks like when it is dramatized.

Žižek helps us see how resistance can be enjoyed as identity. Badiou helps us see how perseverance without Event is politically empty. Together, they expose the limits of a culture that congratulates itself on knowing that the struggle never ends. What is missing is not realism but courage: the courage to imagine that repetition itself might be the problem. To imagine an end to the battle is not to imagine utopia or final harmony. It is to risk asking whether the coordinates of the struggle could be transformed so radically that the enemy, as we know it, would no longer make sense.

Such an imagination is dangerous: it threatens identities built around opposition, moral clarity, the comfort of knowing one’s place in the fight. This is why consolation so often takes the form of repetition. Better another battle than a leap into the unknown.

One Battle After Another is a serious film. Its refusal of easy victory is honest. But honesty is not enough. The danger is that honesty becomes an alibi for resignation. A Žižekian reading warns us that endless resistance can become ideology. A Badiouian reading warns us that without rupture, there is no politics at all. Together, they force a harder question upon us: Are we fighting because the world must change—or because fighting itself has become our way of surviving a world we no longer believe can? To reject consolation today is not to demand optimism. It is to refuse the comfort of repetition. It is to insist that politics, if it is to mean anything, must risk more than endurance.

Otherwise, there will always be another battle—and nothing else.

Sam Ben-Meir is an assistant adjunct professor of philosophy at City University of New York, College of Technology.