In some Latino communities, Thanksgiving is playfully called “Sanguiving,” or holy giving. This play on words shifts the focus from simple thanks to the act of giving itself. Around a shared table, no one is meant to be left alone. For a brief moment, generosity feels sacred — before the machinery of consumption resumes on Black Friday.

In reframing the holiday this way, something underlying it is made visible. What this distinctly American celebration has long carried within it is the idea that “having” implies responsibility — that wealth, power, and success require giving back.

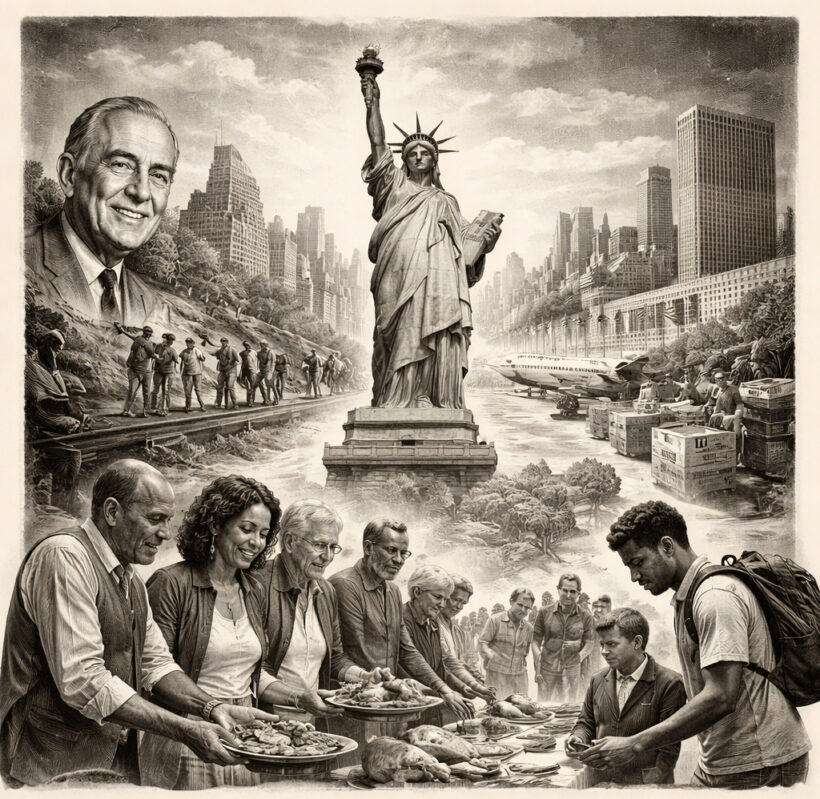

For a long period, this ethic of responsibility was embedded in American institutions. The U.S. became, arguably, the largest giving machine in the world. Paying taxes was understood not simply as a legal obligation, but as a contribution to a shared pool of resources that would later be redistributed according to politically evaluated needs within the community. Corporations absorbed this logic and began to institutionalize the idea of “giving back” by founding foundations and supporting NGOs and local social organizations.

From the New Deal through the post–World War II decades, paying taxes was accepted as a civic contribution that funded social security, public infrastructure, education, and healthcare. Under Franklin D. Roosevelt, progressive taxation helped build a social contract in which prosperity implied responsibility. Federal revenues funded Social Security, which by the 1950s covered tens of millions of Americans, as well as massive public works through programs such as the WPA and the CCC, which together built or improved hundreds of thousands of miles of roads, tens of thousands of bridges, schools, libraries, hospitals, parks, and dams—many of which still serve communities today. Redistribution was framed not as charity, but as a structural obligation of a functioning democracy (and also, given the rise of global communism and fascism, as a way of saving that democracy).

This logic extended well beyond the New Deal years. Between 1944 and 1963, the top marginal federal income tax rate on the wealthiest Americans ranged from 91% to 70%, while corporate tax rates averaged 40–52%. Far from undermining growth, this period coincided with unprecedented economic expansion, the rise of the middle class, and large-scale public investment in housing, scientific research, and higher education. By contrast, today the top marginal income tax rate stands at 37%, and the corporate tax rate was reduced to 21% in 2017—less than half its postwar level. Public investment has followed the same trajectory: while infrastructure, education, and research spending once exceeded 4–5% of GDP, it now hovers closer to 2–2.5%, despite a far larger and wealthier economy.

This ethic of responsibility was reinforced by thinkers such as Andrew Carnegie, who argued in The Gospel of Wealth that large fortunes were morally defensible only if reinvested for the public good—an idea he enacted by funding thousands of libraries and cultural institutions across the country. The same logic was later absorbed by American corporations, which institutionalized “giving back” through permanent philanthropic structures. Major foundations and corporate programs supported education, public health, civil rights, and cultural life, while local communities benefited from sustained investment. Together with a dense network of nonprofits, these efforts reflected a shared assumption: wealth—whether collected through taxes or generated by private enterprise—was not fully legitimate unless it circulated back into society.

This capacity to give was not limited to domestic life. From 1945 onward, the United States granted lawful permanent residency to well over 60 million immigrants, making it one of the largest receivers of migrants in modern history. Internationally, the U.S. also positioned itself as a central engine of reconstruction and development aid, supporting postwar recovery and later health, education, and development efforts across the Global South. These actions reinforced the idea that American prosperity carried responsibilities beyond national borders.

Another central expression of this collective giving at the global level was the United States’ decisive role in the creation and long-term support of the United Nations. Emerging from World War II as a dominant economic and political power, the U.S. was not only a founding member of the UN but also its principal architect and host, offering New York City as the organization’s permanent headquarters. For decades, the United States was the largest financial contributor to the UN system and its specialized agencies, supporting peacekeeping operations, humanitarian relief, refugee protection, public health, education, and international law. This commitment reflected a belief—however imperfectly realized—that global stability and human dignity were collective responsibilities, and that American power carried an obligation to sustain multilateral institutions serving the common good.

What once made America “great” was precisely this capacity to give—an ability that generated international trust and moral authority. Happiness, in the background, was closely linked to one’s capacity to give, while gratitude was understood as a natural social bond rather than a debt. At a certain point, however, the system began to measure giving — to optimize it, monetize it, and eventually turn it into a business. Institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund integrated calculation and efficiency metrics into the act of giving itself. Gradually, the logic shifted from responding to need to prioritizing efficiency, replacing moral urgency with cost-benefit analysis.

The situation we face today is the continuation of this process: the marketization and privatization of giving, stripped from the social, political, and cultural structures that once sustained it. If we are to understand what happened to us, perhaps it is this—we lost our capacity to give freely. Today, to give something often means first having to buy it. Calculation replaced generosity; self-interest overtook collective responsibility. Along this road, individuals and institutions alike began to ask: why should I give in the first place? Why not keep what I have? Why can’t others solve their own problems?

Here we are now, with a social and political system riddled with contradictions, running a broken giving machine—inhabited by individuals lost and uncertain about the meaning of their own lives, and even more uncertain about society as a whole. Corporations have become increasingly greedy, and an extreme concentration of economic power in the hands of a few allows them to shape and control billions of lives, placing entire populations at the mercy of their selective, strategic, and deeply conditional “generosity.”

As Silo insisted, meaning does not arise from accumulation, success, or efficiency, but from direction. In The Inner Look, he writes that an action is valid only when it “does not produce contradiction” in oneself or in others, and when it contributes to the overcoming of suffering rather than its reproduction. Giving, in this sense, is not generosity as spectacle or calculation, but a way of being aligned with one’s deepest intention. When societies lose this orientation, they do not merely become unjust—they become disoriented. Perhaps what we are facing today is not simply an economic or political crisis, but the consequence of having abandoned valid action itself: the quiet forgetting that meaning is born not from what we keep, but from what we give.