by Asif Showkat Kallol ( Dhaka Bureau)

Bangladesh’s interim government has found itself navigating a deepening economic crisis, weighed down by a mountain of debt accumulated during the tenure of the ousted Awami League administration. What was once presented as a development-driven borrowing strategy has now hardened into a structural burden, forcing the state into a cycle of debt repayment financed by fresh loans- a pattern economists warn is unsustainable.

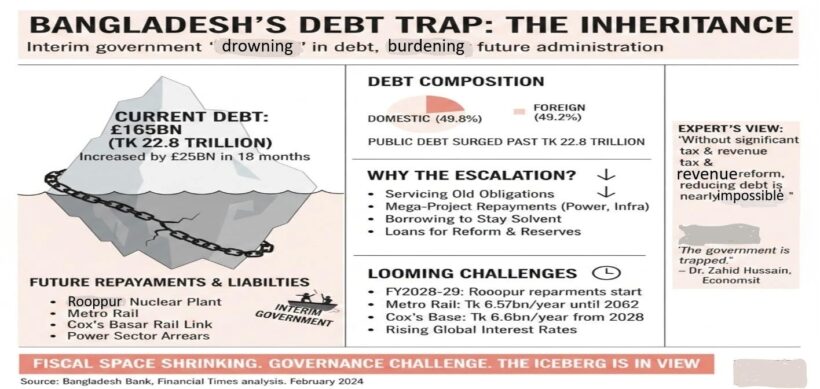

According to Bangladesh Bank data, the country’s total public debt has surged past Tk 22.8 trillion (£165bn), marking an unprecedented level in the nation’s history. Of this, domestic borrowing stands at approximately Tk 11.39 trillion, while foreign debt has risen to Tk 11.77 trillion. When the Awami League government fell from power, total debt stood at around Tk 19.23 trillion. In just eighteen months under the interim administration, liabilities have increased by more than Tk 3.58 trillion — the first time annual net borrowing has exceeded Tk 3 trillion.

The reasons for this rapid escalation are less about policy ambition than fiscal compulsion. A substantial share of current borrowing is being used not for new development projects, but to service old obligations- repaying instalments and interest on loans contracted in earlier years, particularly for power, energy, and infrastructure megaprojects. In effect, the government is borrowing to stay solvent.

Over the past year and a half, Bangladesh has taken more than $3.5bn in loans from multilateral lenders, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, ostensibly to support reform programmes and stabilise dwindling foreign exchange reserves. At the same time, the interim government has been forced to clear roughly $2.5bn in arrears owed to power producers and fuel suppliers — liabilities inherited from years of aggressive energy expansion financed by opaque contracts and capacity payments.

What lies ahead is even more daunting. From the 2028–29 fiscal year, Bangladesh will begin repaying instalments on the Rooppur nuclear power plant, a flagship project whose cost has ballooned to Tk 1.39 trillion. Annual repayments for the Uttara-Motijheel metro rail are expected to average Tk 6.57bn until 2061-62, while loan repayments for the Cox’s Bazar rail link financed by the Asian Development Bank will rise to Tk 6.6bn annually from 2028.

‘These are not short-term pressures,’ said economist Dr Zahid Hussain. ‘Unless tax collection and revenue mobilisation improve significantly, reducing the debt burden will be nearly impossible. The government is trapped between rising debt repayments and mounting recurrent expenditures.’

That trap is tightening. Alongside debt servicing, the interim administration is grappling with growing demands for higher public sector wages, subsidies to contain inflation, and social spending to cushion economic hardship. With revenue growth stagnant and tax compliance weak, fiscal space is shrinking fast.

For now, the interim government’s role is largely custodial. But analysts warn that the real political and economic reckoning will arrive after the national election scheduled for 12 February, when an elected government takes office. That administration will inherit not only the authority to govern, but also the full weight of a debt structure that will dominate its entire term.

Critically, much of this debt is tied to projects whose economic returns remain contested. While megaprojects were long promoted as symbols of modernisation, their repayment schedules now coincide with slowing growth, pressure on foreign reserves, and limited export diversification. As global interest rates remain elevated, the cost of external borrowing has also risen, further straining public finances.

The interim government insists it has little choice. Default is not an option, and slashing development spending risks deepening economic stagnation. Yet continuing to borrow to repay earlier loans only postpones the problem- and magnifies it.

What Bangladesh faces is not merely a fiscal imbalance but a governance challenge. Years of politically driven borrowing, weak oversight, inflated project costs, and inadequate revenue reform have left the state exposed. Debt, once framed as an investment in the future, is now shaping- and constraining- that future.

For the next elected government, the danger is clear. Without decisive reforms in tax policy, expenditure discipline, and project selection, debt servicing will crowd out development, social protection and political ambition alike. The iceberg is already in view. Whether Bangladesh can change course before impact remains uncertain.

————————

The author:

Asif Showkat Kallol: Head of News, The Mirror Asia and Contributor, Pressenza- Dhaka Bureau.

Asif Showkat Kallol: Head of News, The Mirror Asia and Contributor, Pressenza- Dhaka Bureau.