by Asif Showkat Kollol (Dhaka Bureau)

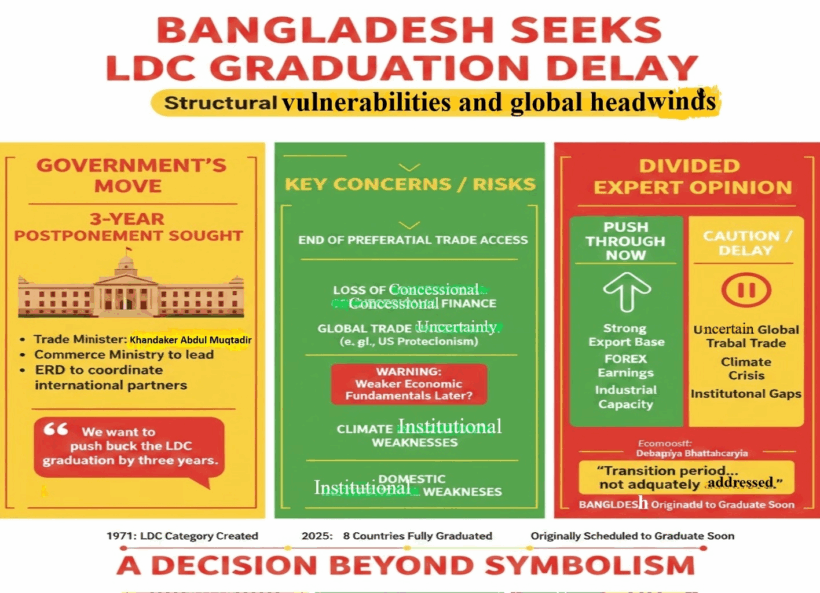

Bangladesh has formally begun efforts to seek a three-year postponement of its graduation from Least Developed Country (LDC) status, reopening a debate over whether the country is better served by delay or by confronting the risks of transition head-on.

Speaking to reporters at the Secretariat on Wednesday, the first working day of the new cabinet, Trade, Industry and Textiles Minister Khandaker Abdul Muqtadir said the government had already initiated steps to defer the graduation timeline.

‘We want to push back the LDC graduation by three years. We have started working on this from today and will take all necessary steps,’ he said, adding that the Ministry of Commerce would lead the process, while the Economic Relations Division (ERD) would coordinate with international partners.

The announcement comes at a sensitive moment for Bangladesh, which is currently scheduled to graduate after meeting key United Nations criteria in two consecutive assessments. Graduation would mark the end of preferential trade access, concessional finance and certain forms of development assistance that have underpinned the country’s export-led growth.

Political transition, economic caution

Muqtadir, elected to parliament for the first time, was appointed amid a broader political transition. Newly appointed state minister, Md. Shariful Alam, a senior organisational leader of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), was also present at the briefing and will oversee commerce, industry, textiles and jute.

While LDC graduation is often framed as a development milestone, the BNP-led government’s move has raised eyebrows, particularly given its own historical record. During the early 2000s, Bangladesh successfully navigated the phase-out of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement (MFA), a potentially devastating shock to the garment sector, under the stewardship of then finance minister Saifur Rahman.

That experience has prompted a central question among economists and policymakers: why does a government that once confronted global trade shocks head-on now seek to delay LDC graduation?

A divided expert opinion

Opinion within policy circles is sharply divided. One group of economists argues that Bangladesh should confront graduation now, while its export base, foreign exchange earnings, and industrial capacity remain relatively robust. Delaying the transition, they warn, risks pushing the country into a future moment when its economic fundamentals may be weaker.

That concern is sharpened by the current global trade climate. The return of protectionist rhetoric and reciprocal tariff policies under US President Donald Trump has injected volatility into the global trading system. In such an environment, critics argue, postponing graduation could mean facing LDC exit under even harsher external conditions later.

Others counter that uncertainty itself justifies caution. A more hostile global trade regime, coupled with climate vulnerability and domestic institutional weaknesses, could make an abrupt withdrawal of LDC support economically destabilising.

Rethinking the graduation model

Beyond Bangladesh, the debate reflects deeper concerns about the global LDC graduation framework. Economist Debapriya Bhattacharya, a distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue, has argued that the model itself is structurally flawed.

‘The ultimate goal is graduation,’ Bhattacharya notes, ‘but the transition period and the readiness of countries to withstand post-graduation shocks have not been adequately addressed.’

The LDC category, created by the United Nations in 1971, was designed to support countries facing deep structural barriers. Yet more than five decades later, progress has been uneven. LDCs account for about 12% of the world’s population but contribute only 2% of global GDP and 1% of world trade, while hosting a disproportionate share of refugees and climate-vulnerable communities.

Graduation decisions are made by the UN Committee for Development Policy, based on income, human assets, and economic and environmental vulnerability. By 2025, only eight countries had fully graduated, while dozens remain stuck in the category.

A decision beyond symbolism

For Bangladesh, the choice is no longer symbolic. Delaying graduation may offer breathing space to strengthen institutions and diversify exports, but it also risks signalling hesitation to investors and development partners.

What is increasingly clear is that LDC graduation is no longer seen as an unqualified victory. In an era of climate crisis, geopolitical instability, and fragmented globalisation, the real question is not just when countries graduate, but whether the international system is prepared to support what comes after.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

The Author:

Asif Showkat Kallol: Germany-based online outlet, Head of News, The Mirror Asian & Contributor, Pressenza- Dhaka Bureau.

Asif Showkat Kallol: Germany-based online outlet, Head of News, The Mirror Asian & Contributor, Pressenza- Dhaka Bureau.