When Barbados Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley posed her question to the heart of the global financial order—why was quantitative easing anathema to the Global South until the G7 needed it?—she was not making a technical inquiry. She unleashed a moral challenge onto the table of those who govern the world economy. Her question is the finger pointing at the festering wound of our system: structural hypocrisy as a principle of financial governance.

Below is an audio transcription of the brief interview with Mia Amor Mottley, shared on YouTube, regarding “quantitative easing.” In it, the Prime Minister of Barbados challenges dominant views and explains the impact of this double standard. She asks why ‘credit quantitative easing’ is not “recommended” for countries where needs are greatest.

January 7, 2026, 23:57

“How is it possible that quantitative easing was not recommended to countries around the world before COVID, but as soon as COVID hit, G7 countries carried out the largest exercise in quantitative easing ever known? How is it possible that Ghana and other African countries are borrowing at interest rates several times higher than those of European countries, under circumstances where the needs are greater and where there is no clear explanation? You can talk to me about safe assets and you can wrap it all up in technical language, but when all is said and done, what exists is a fundamental disparity.

How is it possible that quantitative easing was not recommended to countries around the world before COVID, but as soon as COVID hit, G7 countries carried out the largest exercise in quantitative easing ever known? How is it possible that Ghana and other African countries are borrowing at interest rates several times higher than those of European countries, under circumstances where the needs are greater and where there is no clear explanation? You can talk to me about safe assets and you can wrap it all up in technical language, but when all is said and done, what exists is a fundamental disparity.”

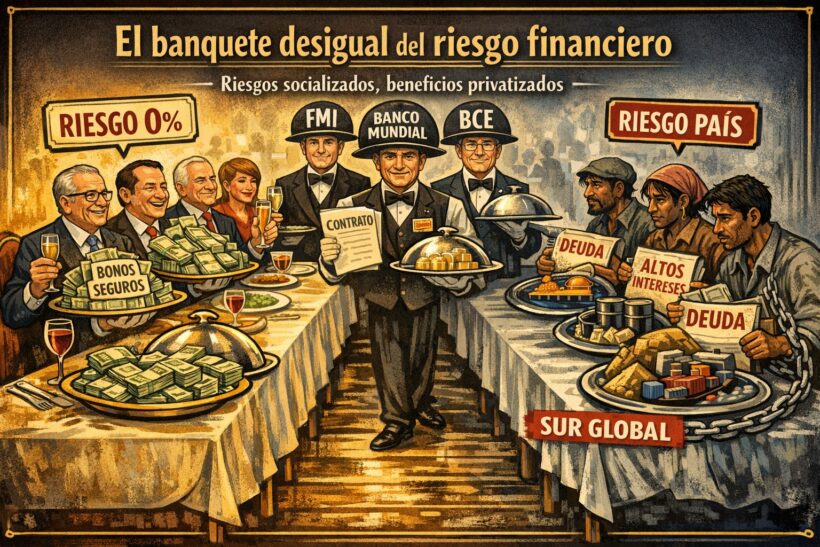

For decades, the Global South—Africa, Latin America, much of Asia—was denied the right to use expansive monetary tools. The mantra was singular: prudence, stability, risk. We were subjected to exorbitant interest rates, draconian austerity programs, and suffocating surveillance, all under the threat of inflationary chaos and fiscal collapse. We were undisciplined pupils who needed to be subjected to a rigor that, apparently, only we required.

Then COVID-19 arrived. And the most cynical magic trick in recent economic history occurred. When the virus hit the G7 metropolises, the “risk” vanished. Overnight, the central banks of the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom created trillions of dollars and euros out of thin air. They massively bought their own debt, flooded the markets with liquidity, and socialized losses on a planetary scale. And the world did not end. Inflation, when it came, was managed. The apocalypse forecast for us to justify austerity was, for them, merely a management problem.

The question burns in the air: if this tool is safe and effective for the powerful, why does it become a crime when others need it? This is where the farce of “country risk” is exposed and laid bare. We are told that the stratospheric interest paid by Mozambique, Ecuador, or Pakistan is the fair price of their “risk.” A technical, neutral, inevitable category. But let’s scratch the surface of those loans.

What are they for? Often, to finance extractive infrastructure, strategic ports, logistical corridors, and energy networks that connect the raw materials of the South with the markets and factories of the North. And who builds, operates, and benefits? Predominantly, consortia and companies from the G7 and G20. Contracts are armored with predatory clauses. Revenue flows, guaranteed. Assets, under foreign control. Operational and political risks, externalized onto the recipient state.

In other words, the lender already controls the infrastructure, already secures its return, already dictates the conditions… and yet, still charges a premium for a “risk” it does not bear. The risk does not disappear; it is transferred entirely onto the shoulders of the debtor state, its population, and its economic sovereignty. It is an inverted risk: the one assumed by the borrower is infinitely greater than that of the creditor.

This is the core of the scandal: a monetary double standard that is, in essence, an instrument of neocolonial control.

While the European Central Bank buys Italian or Greek debt to calm the markets, Zambia or Sri Lanka are required, to receive a bailout, to dismantle their public health systems, sell off national assets, and hand over the reins of their economic policy to bureaucrats in Washington or Frankfurt. Some socialize risk to protect their citizens; others must privatize their sovereignty to survive, while also financing projects that enrich those who lend to them at high cost.

This is not a technical disparity. It is a political hierarchy. It is a system designed to extract rents, secure profits, and discipline dissenters. “Country risk” is the elegant alibi for an architecture of plunder. A neocolonialism without soldiers, but with lawyers, economists, and derivatives contracts.

This is why Mottley’s question and argument land with the force of a hammer: —Who truly bears the risk and the cost? And if the honest answer is that it is not the lender, then the final question is the most uncomfortable, the most necessary, the one that must guide our outrage and our action: —Why on earth do we keep paying as if they did?

The silence that follows this question is not one of perplexity. It is the confirmation that the global financial order is not based on economic science, but on the law of the strongest. And every unjust law deserves, before obedience, tenacious resistance. The battle for financial justice is not technical. It is profoundly political. And it has begun.

This battle has indeed already moved beyond the realm of diagnosis and denunciation. It is being waged on the concrete terrain of alternative financial architecture. Emerging structures, like the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB), created precisely to finance infrastructure and development projects without the predatory conditionalities of the old order. That is, loans tailored:

- without demanding adjustment and austerity programs,

- without forcing cuts to basic services,

- without imposing the privatization of strategic assets, and

- without the interference of external supervision, where investments aligned with G7/G20 interests typically assume economic control or even involve the deployment of military or paramilitary (base) oversight.

These institutions or instruments of economic cooperation represent a direct political challenge, as the recipient country is also not interfered with in matters of domestic politics or pressured to adopt foreign policy stances (to the lender’s convenience). They are an institutional attempt to rewrite the rules of the game.

Similarly, in the Caribbean, the efforts toward financial integration and mutualization within the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) are based on principles of sovereignty and cooperation, not extractive conditionality. These are not mere acronyms or bureaucracies; they are trenches in the geopolitical contest for economic justice and sectoral collaboration.

The struggle for financial justice is not technical. It is profoundly political, and it has begun in the hallways of the New Development Bank, at the summits of Caribbean unity, and in every forum where the historically excluded organize to, finally, stop asking for permission and start building alternatives.