Abstract

This paper advances a structural hypothesis on the behavior of declining hegemonies and their impact on the reconfiguration of the contemporary international order. It argues that when a power simultaneously loses productive, technological, and normative primacy, with no short-term prospects of reversal, it tends to abandon the order it created and to actively transform it into a dysfunctional system for emerging actors. Through a deliberate cross-reading of classical power theory (Machiavelli), critical international political economy, infrastructure geopolitics, and strategic prospective analysis, the study examines the transition from normative hegemony to a model of structural blackmail based on the control of systemic chokepoints. Using scenarios and the case of Venezuela as an operational prototype, it analyzes the role of South America—particularly Chile, Bolivia, and Brazil—as an intermediate board in the struggle over routes, logistical nodes, and critical resources. The paper concludes that the current historical moment does not represent an orderly transition toward multipolarity, but rather a phase of active sabotage of the international system by the declining hegemon, whose limits are defined by the visibility of coercion, infrastructure redundancy, and coordinated responses by emerging actors.

Introduction

The liberal international order is not merely eroding: it is being actively dismantled by the power that designed and sustained it for decades. This distinction is fundamental. What we are witnessing is not a spontaneous systemic collapse, but a conscious strategic decision adopted by a hegemonic power that has lost its productive, technological, and normative primacy and no longer derives sufficient benefit from preserving the order it once established.

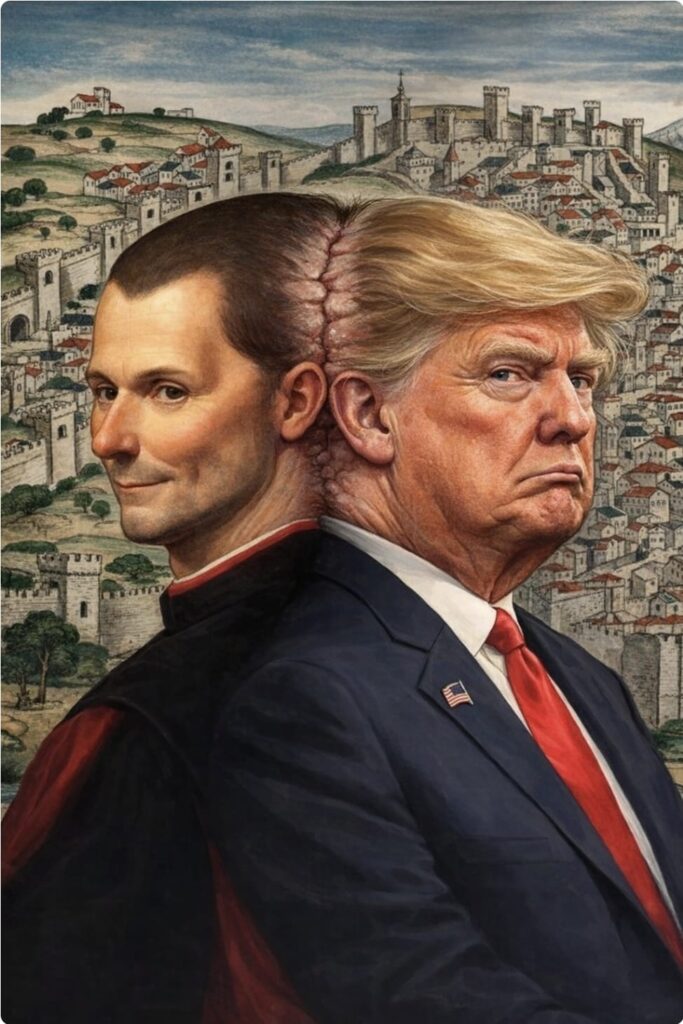

Donald Trump’s return to the presidency of the United States did not inaugurate this dynamic, but it exposed it without ambiguity. The direct intervention in Venezuela—entailing the capture of the head of state, de facto external administration, and the explicit suspension of all normative restraint—marks a qualitative turning point: the moment when the Prince overturns the board, removes the mask, and signals to the international system that the rules structuring the post–Cold War era are no longer binding upon him.

The central hypothesis of this work is the following: when a hegemonic power simultaneously loses productive, technological, and normative primacy, and lacks viable mechanisms to reverse that decline in the short term, it tends to abandon the international order it created and to actively transform it into a system of strangulation for emerging actors. Instead of normative leadership, it exercises systemic coercion; instead of universal rules, it administers exceptions; instead of direct territorial domination, it captures critical chokepoints that allow it to control the time, cost, and friction of global flows.

This essay combines classical power theory, critical international political economy, infrastructure geopolitics, and strategic prospective analysis. Through scenarios and the use of prototypical cases, it seeks to assess the durability of this model of power and its implications for South America within the context of systemic competition between the United States and emerging actors, particularly China.

Theoretical and Methodological Framework

The adopted approach is based on a deliberate theoretical cross-reading. First, it reclaims Machiavelli not as an ornamental historical figure, but as a privileged analyst of power under conditions of existential threat. Machiavellian thought is particularly relevant for studying declining hegemonies, as it was conceived for princes facing loss of control, erosion of legitimacy, and the necessity of acting outside conventional moral frameworks.

Three concepts are central: necessità, understood as the obligation to act according to the requirements of state survival; virtù, not as ethical virtue but as the effective capacity to intervene in the course of events; and fortuna, conceived as the active management of crisis and contingency. In the twenty-first century, virtù no longer primarily resides in productive capacity, but in the ability to slow down, increase the cost of, or fragment the advance of others.

This framework engages with critical international political economy and contemporary literature on hegemonic decline and infrastructure geopolitics, which identify the control of nodes, standards, logistical routes, and payment systems as central forms of power in late capitalism. It also incorporates strategic prospective analysis as a methodology, using scenarios as heuristic tools and the concept of the prototype to identify extrapolable operational patterns.

Structural blackmail is defined here as the capacity of an actor to impose conditions on others not through direct prohibition or overt military coercion, but through control over the time, cost, and friction of systems upon which all depend.

From Normative Hegemony to Structural Blackmail

During its ascendant phase, the United States governed the international system through norms, multilateral institutions, and consensuses that, while asymmetrical, offered predictability and shared benefits. With the rise of China, the consolidation of alternative value chains, and the emergence of blocs such as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), the cost of sustaining that order progressively exceeded its benefits.

The response was not reform, but transformation of the system into hostile terrain for competitors. This shift manifests in a series of structural transitions: from multilateralism to permanent exception justified by national security; from trade as a mechanism of integration to trade as a weapon; from international law to jurisdiction by capture; from symbolic deterrence to the pedagogy of fear; and from territorial control to control of systemic chokepoints.

The intervention in Venezuela must be understood as an operational prototype rather than an anomaly. It represents the upper limit of a logic that can take less visible but equally coercive forms in other regional contexts.

Systemic Chokepoints as the New Unit of Power

In the contemporary scenario, the central unit of analysis is no longer exclusively the nation-state, but the node. Power is exercised by controlling maritime routes, bioceanic corridors, straits, ports, inland logistical nodes, legal frameworks, technical standards, and financial systems.

Squeezing a chokepoint is more effective than occupying a territory. Flows are not prohibited; they are slowed. Access is not denied; it is conditioned. This form of power allows coercion at low initial political cost and high systemic effectiveness.

In South America, the main chokepoints include the Panama Canal, the Strait of Magellan, South Pacific ports, bioceanic corridors, inland dry ports, and critical resources whose extraction depends on complex logistical infrastructure.

South America as an Intermediate Board

Chile functions as a stable node and Pacific gateway. Its high level of trade integration with China, institutional stability, and potential role as an articulator of bioceanic corridors make it an uncomfortable anomaly for a hegemon seeking to control the rhythm of trade. Pressure on Chile takes the form not of direct intervention, but of environmental, legal, financial, and logistical conditioning.

Bolivia represents the ideal capture point. It possesses lithium and potential rare earth resources, but lacks sovereign access to the sea and is critically dependent on infrastructure. Controlling the Bolivian node allows simultaneous conditioning of Chile, Brazil, and China without formal occupation.

Brazil, for its part, is not a target of direct capture but of conditioning. Its productive scale, BRICS membership, and promotion of bioceanic corridors make it a central systemic actor. Pressure is exerted through a combination of logistical friction, trade disputes, and internal tensions.

The Late Capture Scenario

The late capture scenario cannot be understood as a technical episode or an isolated regional variant. It is, rather, the most refined operational expression of the strategy of the declining Prince, deployed at a hemispheric scale. To grasp it, one must reconstruct the full board on which it unfolds.

The Prince does not act impulsively or country by country. He acts on systems. His rationality is not territorial in the classical sense, but logistical, temporal, and structural. Controlling space is no longer sufficient; what matters is controlling the time of trade, the friction of flows, and dependence on nodes. From this perspective, the political geography of the present is organized around routes, chokepoints, and transit architectures.

The board begins in the north. Greenland shifts from marginal space to central strategic point with the progressive opening of Arctic routes that shorten transport times and reconfigure global trade. Canada, far from being homogeneous, is traversed by internal tensions, particularly in Alberta, where energy, resources, and provincial pressures become vectors of external influence. Mexico, especially its northern strip, consolidates as a permanently securitized zone, serving as social and logistical buffer for the Prince’s southern frontier. The Caribbean, with Haiti and Cuba, performs a dual function of containment and warning.

Within this same axis lies Panama. The canal is not merely inherited infrastructure; it is a classic choke point reactivated by the Prince as an instrument of pressure in a context where route control regains centrality. As global trade densifies and diversifies, the canal’s strategic value increases not through monopoly, but through its capacity for selective friction. At the same time, the sustained rise in traffic through the Strait of Magellan introduces a natural bypass that threatens that centrality, enhancing the relevance of the continent’s southern extreme.

It is within this hemispheric framework that South America shifts from periphery to decisive intermediate board. The Prince cannot control all global flows simultaneously, but he can intervene where they reorganize. South America is one such space—not because of weakness, but because of emerging centrality.

Argentina appears as territory of forced negotiation. The Prince need not conquer it; it suffices to extract what, in Machiavellian terms, can be read as a right of passage. Pressure on the government of Javier Milei translates into demands for two strategic anchors: a southern base oriented toward bioceanic and Antarctic control and Magellan traffic, and another along the Aguas Negras axis, key for mining and Atlantic–Pacific corridors. This is not defense, but structural positioning.

Chile constitutes a more delicate case. Its institutional stability, high degree of trade integration with China, and role as Pacific gateway make it difficult to discipline through classical mechanisms. In this context, the inauguration of the port of Chancay in Peru, financed and operated with Chinese participation, substantially alters the regional logistical balance. It not only creates a large-scale port node, but enables a direct Peru–Brazil vector that may become an alternative bioceanic corridor, shifting the South Pacific center of gravity northward and reordering dependencies.

The Peru–Brazil axis articulated from Chancay introduces a strategic novelty of the first order. It offers Brazil Pacific access without passing through Chile or Bolivian inland nodes, under a logistical architecture closely associated with China. For the Prince, this is doubly problematic: it consolidates infrastructure that reduces strangulation capacity while weakening the effectiveness of any blackmail based on a single corridor. Hence, the Prince’s response is not simply to block, but to reinsert himself, manage corridor competition, and prevent any architecture from becoming fully autonomous.

In this light, Chile’s port modernization process undertaken in agreement with the United States after Chancay’s opening should be read not as neutral cooperation, but as an attempt to recentralize flows, retain South Pacific leverage, and keep Chile within a negotiation perimeter where the Prince preserves pressure capacity.

Brazil completes the picture as an unavoidable actor. By scale, BRICS membership, and Atlantic projection, Brazil cannot be captured—only conditioned. The Prince’s strategy thus introduces logistical friction, trade disputes, and internal tensions aimed at limiting Brazilian strategic autonomy and, above all, preventing Brazil from consolidating two robust bioceanic outlets simultaneously: one via Peru–Brazil and another via Chile–Bolivia–Brazil or its Argentine variants.

In parallel, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) traverses this space without declaring itself geopolitical while functioning as such. From Panama southward, the multiplication of port, rail, and logistics projects configures an alternative architecture that reduces dependence on chokepoints controlled by the Prince. Its framing as pragmatic trade facilitation makes it difficult to counter without political exposure.

At this juncture, the late capture scenario reveals its bifurcated character. The Prince does not bet on a single logistical architecture; he manages contingencies. If the Chile–Bolivia–Brazil axis consolidates as dominant corridor, the most efficient capture point shifts to the Bolivian inland node, through control of dry ports, customs governance, certifications, insurance, and compliance standards. If, instead, the Peru–Brazil axis articulated from Chancay prevails, capture occurs not at a single physical node but within the regulatory, financial, and logistical plane of the corridor itself, via administrative friction, financing conditionality, and indirect flow control.

In both cases, the logic is the same. The Prince does not block infrastructure; he allows it to mature. He permits investment, commitment, and dependence. Only then does he introduce control—not through occupation or open confrontation, but under functional pretexts: security, counter-narcotics, technical standards, regulatory compliance. The Prince does not prohibit; he administers. He does not dominate territory; he governs friction.

In this way, he can extract lithium and rare earths on his own terms while simultaneously conditioning Chile, Brazil, and China, at minimal initial political cost. This is the most refined form of structural blackmail: domination without occupation, coercion without declaration, control without formal responsibility. In a board with competing alternative routes, the objective is not necessarily to destroy them, but to prevent full redundancy and autonomous governance, keeping them within a manageable zone of dependence.

This scenario is not permanent. It depends on the invisibility of control, the fragmentation of architectures, and the absence of fully operational redundancies. But as long as these conditions hold, the Prince achieves precisely what he seeks in decline: not the recovery of lost hegemony, but the prevention of its stabilization by others.

Thus, the late capture scenario is not an accessory chapter, but the convergence point of the entire strategy analyzed. It is here that the Prince, mask removed, displays his true virtù: not the creation of order, but the administration of others’ disorder.

Expanded Conclusions

The analysis yields several general conclusions. First, the current phase of the international system should not be read as an orderly transition toward multipolarity, but as a period of active sabotage by the declining hegemon. This strategy does not aim to restore lost leadership, but to prevent others from consolidating theirs.

Second, the shift of power toward control of systemic chokepoints redefines sovereignty. States may formally retain autonomy while losing effective decision-making capacity over the flows sustaining their economies. Sovereignty is hollowed out without being abolished.

Third, structural blackmail has clear limits. Its effectiveness declines as control becomes visible, redundant infrastructures emerge, and affected actors coordinate responses. The inverse dependence generated by this model partially turns the blackmailer into a hostage of the very system he seeks to dominate.

Finally, the South American case demonstrates that the core dispute is not over isolated resources, but over the architecture that transforms those resources into power. In this context, the capacity to design unblackmailable infrastructures, with distributed governance and operational redundancy, becomes a central form of strategic defense.

The decisive question is no longer whether the Prince can squeeze chokepoints, but how many he can squeeze before the system ceases to tolerate it and accelerates its reorganization beyond his control.