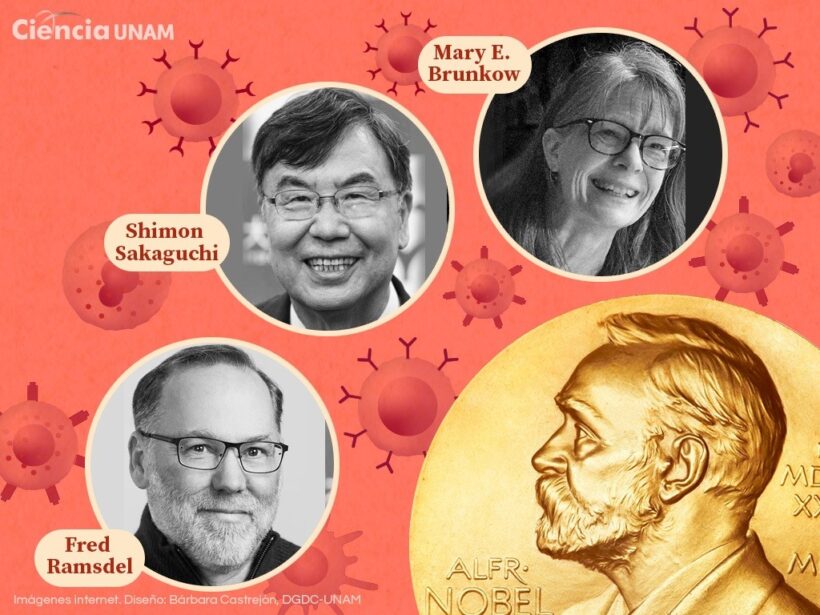

In a world where the immune system can be both hero and villain, three scientists have illuminated the path to taming its excesses. On October 6, 2025, the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute announced that Mary E. Brunkow, PhD; Fred Ramsdell, PhD; and Shimon Sakaguchi, MD, PhD, would share the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries on “peripheral immune tolerance.” This breakthrough explains how the body avoids autoimmune attacks, opening doors to treatments that could cure diabetes, arthritis, and cancer. Their work, born in humble laboratories, promises an era of precise therapies where the immune system is restored, not just suppressed.

The pioneers: Careers and legacies

Shimon Sakaguchi, distinguished professor at Osaka University, Japan, leads the Experimental Immunology Laboratory at the same institution’s Cancer Research Center. Born in 1955, Sakaguchi combined immunology and genetics in the 1990s. His curiosity about why some mice rejected transplants led him to challenge dogmas: tolerance does not only occur in the thymus (organ where T cells mature), but in the periphery of the body.

Mary E. Brunkow, principal investigator at the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, USA, specializes in the genetics of immunodeficiencies. With a doctorate in molecular immunology, Brunkow worked at Genentech before joining ISB. Her focus on genetic mutations positioned her to decipher rare enigmas.

Fred Ramsdell, now chief scientific officer at Sonoma Biotherapeutics in Mountain View, California, USA, is a bridge between basic science and clinical practice. With a PhD in immunobiology from the University of Texas, Ramsdell passed through Genentech and NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). His entrepreneurial vision accelerates Treg therapies in human trials.

Together, these researchers transformed hypotheses into molecular mechanisms, as detailed in the Nobel statement: “Through insightful observations and carefully designed experiments, the Laureates provided a molecular explanation of active peripheral tolerance.”

The scientific core: From mystery to FOXP3

Imagine the immune system as a vigilant army. T cells (T lymphocytes, key white blood cells) attack invaders, but some “autoreactive” ones escape the thymus and could damage healthy organs. The question was how chaos is stopped. The answer lies in regulatory T cells (Treg, from English: Regulatory T cells), a subgroup of CD4+ T helper cells that express CD25 (alpha subunit of the IL-2 receptor, interleukin-2) and the FOXP3 transcription factor (Forkhead box P3, master gene of Treg differentiation).

Sakaguchi published the seminal paper in 1995: “Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells: induction of autoimmune disease by breaking their anergic state” (Journal of Immunology, vol. 155, pp. 1151-1164). Here he demonstrated that transferring CD25+CD4+ Tregs to mice induced tolerance to self-antigens, suppressing autoimmunity. Then, Brunkow and Ramsdell entered with the “scurfy” model (mice with X-linked mutation that die young from autoimmunity). In 2001, they published “Disruption of a novel forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse” (Nature Genetics, vol. 27, pp. 68-73), identifying FOXP3 (called scurfin) as the mutated gene. In 2002, they followed with “X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy” (Nature Genetics, vol. 32, pp. 889-891), linking FOXP3 mutations to IPEX syndrome (Immune dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-linked). Sakaguchi connected the pieces in 2003: “Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells” (Nature Immunology, vol. 4, pp. 337-342), proving that FOXP3 induces suppressor phenotype in conventional T cells.

Abstract from Sakaguchi’s 2003 paper, translated: “Naturally occurring CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells are critical for the maintenance of immunologic self-tolerance. Here we show that Foxp3, a member of the Forkhead family, acts as a master switch programming their development and function. Ectopic expression of Foxp3 converts conventional T cells into suppressors, while mutations cause lethal autoimmunity.”

Simple explanation: Guardians against internal chaos

For everyone: the immune system is like a guard dog. It barks at strangers (viruses), but doesn’t bite the owner (own cells). Tregs are the trainer who says “quiet,” like a traffic light at a chaotic intersection preventing immune collisions. Without them, the dog attacks everything: type 1 diabetes (pancreas), rheumatoid arthritis (joints), multiple sclerosis (nerves), allergies (excessive responses to pollen), or cancer (tumors that recruit Tregs to hide). Drugs like ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) block them in melanoma, unleashing the immune attack. In transplants, Tregs are injected to prevent rejection in kidneys or livers.

IPEX syndrome illustrates perfectly: children with defective FOXP3 suffer chronic diarrhea (attacked intestine), diabetes (destroyed pancreas), and thyroiditis. They die young without a transplant. The scurfy mice were the puzzle; Brunkow and Ramsdell solved it genetically.

Toward a future of precise healing

This Nobel is not just history: it is a manual for therapies. Clinical trials expand patient Tregs for transplants (avoiding rejection, phase III), infuse Tregs in type 1 diabetes (phase II, protecting pancreatic islets), combine Tregs with CAR-T (chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy) in solid cancer (Sonoma Biotherapeutics leads), edit FOXP3 with CRISPR for lupus and Crohn’s disease (preclinical phase), and test Tregs for long COVID and severe allergies (chronic inflammation). Affecting 50 million in the USA (80% women) and hundreds of millions globally, including mestizo populations in Latin America with high lupus incidence, these therapies could reduce hospitalizations by 30% by 2030.

In December 2025, their Nobel lectures (Sakaguchi: “Regulatory T cells for Immune Tolerance”; Brunkow: “FoxP3/Scurfin: A Key Driver”; Ramsdell: “Translating Basic Science to Therapeutic Opportunities”) inspired thousands. As stated in the PubMed Central review: “Their insights form a translational playbook to restore immune balance.”

Hope shines: millions with autoimmunity could abandon toxic immunosuppressants for treatments that restore natural balance. From scurfy mice to global clinics, Brunkow, Ramsdell, and Sakaguchi show that science heals when it understands internal peace. The future does not suppress symptoms; it restores harmony.