From ancient solstice rituals to shared Abrahamic ethics, the season offers a forgotten civic language of compassion, duty, and renewal.

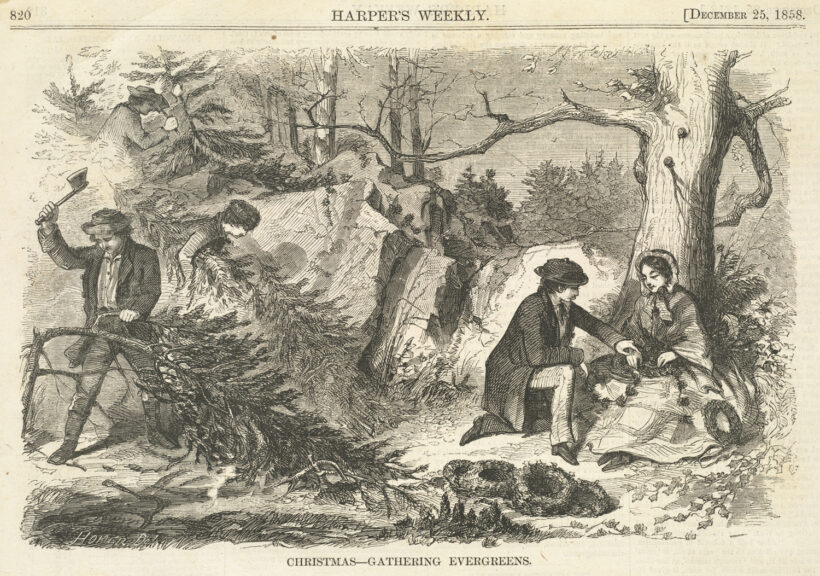

When we think of Christmas today, what comes first to mind? Twinkling lights along Main Street, the ceaseless hum of commerce, the relentless parade of advertisements promising joy measured in price tags. Rarely, if ever, do we pause to consider the ethical marrow beneath this season. And yet, for all its modern commercial veneer, Christmas—like the solstice festivals and civic rituals that preceded it—was once, and could be again, a moral and civic compass pointing toward generosity, compassion, and shared responsibility. Long before Christianity claimed this season as its own, human societies looked to the turning of the year and found in its darkness a lesson not only of survival but also of communal obligation, recognizing that vulnerability, scarcity, and the fragile ties that bind a community demand attention and care. In the forests of Northern Europe, the Yule log burned, a symbol of light returning to the world; in Rome, Saturnalia erupted in feasts and gift-giving, a deliberate inversion of hierarchy, reminding citizens that social cohesion required recognition of all members, even the lowliest; and in the Near East, solstice celebrations marked a liminal time when ordinary rhythms of life were suspended, and moral reflection took precedence over practical concerns.

Across cultures, these seasonal rituals share a common thread: attention to the vulnerable, cultivation of generosity, and the reinforcement of communal bonds. What united these disparate societies was the recognition that humanity flourishes not by the accumulation of wealth or the assertion of dominance, but by generosity, hospitality, and attention to the vulnerable. In these shadows of history, we find the first glimmers of civic duty: the ethical imperative to care for neighbors, to acknowledge the marginalized, to place the health of the community above the satisfaction of individual desire.

When Christianity emerged and incorporated the winter solstice into the story of the Nativity, it did more than assert doctrinal authority; it reinterpreted the old moral lessons through the lens of narrative: the story of a child born in a stable, heralded by shepherds and angels, whose birth was at once humble and cosmic, ordinary and transformative. Here was a story that celebrated vulnerability, humility, and hope, stripped of theological ornamentation, offering an ethical exemplar and telling the listener to pay attention to those on the margins, to protect the weak, to recognize that moral light can shine in the darkest of times. The ethical heartbeat of the season, however, has largely been drowned out in contemporary America. In our hyper-individualistic culture, compassion has been privatized, morality commercialized, and communal attention fractured across economic, racial, and ideological lines. Christmas, once a time to gather, reflect, and renew our obligations to one another, and the social rituals that once cultivated empathy and reinforced civic responsibility, have been reduced to a spectacle of distraction, dead trees, credit card receipts, and gift wrapping, obscuring the enduring potential for ethical reflection and civic repair.

To reclaim this potential, we must trace the ethical throughlines not only through Christian thought but through the shared moral heritage of the Abrahamic religions. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam converge in insisting upon care for the vulnerable, justice, and humility. In Judaism, tzedakah is not optional; it is the act of righteousness, the concrete demonstration that a society’s moral health is measured by how it treats those who have the least. In Islam, zakat functions similarly: wealth is a trust, a means to uphold social solidarity, and a moral duty to support the community’s weakest members. Christianity, through agape, extends love as an ethic: love of neighbor, love of stranger, love that is deliberate and disciplined rather than sentimental or fleeting. Across centuries and continents, these traditions converge on the principle that morality is communal, not merely personal, and a bridge emerges, demonstrating that the ethical lessons embedded in seasonal rituals are not the property of any one faith but a shared inheritance. Across other cultural and spiritual traditions as well, rituals of giving, care, and communal attention underscore the same principles. Recognition of vulnerability, cultivation of generosity, and attention to justice are civic imperatives, as resonant today as they were thousands of years ago.

The Christmas story, in this light, is as much civic as it is spiritual, emphasizing ethical action over dogma, placing the marginalized and vulnerable at the moral center. To give to the poor, to welcome the stranger, to act with humility—these are civic rituals enacted through narrative, story, and symbol. Stripped of theology, Christmas becomes a rehearsal of the social virtues that sustain society. Generosity, humility, and hospitality are not merely sentimental ideals; they are practical guides for civic life. The story of a humble birth, heralded by the lowly, reminds us that the moral and civic duties of a society are inseparable from the care of its most vulnerable members.

Practical reclamation begins with attention. Schools, community centers, and local governments can frame seasonal activities around service, reflection, and ethical engagement rather than solely entertainment. Families can teach children not only the joy of giving but the moral reasoning behind giving. Civic organizations can revive interfaith dialogues, exploring shared values rather than emphasizing doctrinal differences. Individuals, through conscious acts of care, become participants in a civic ritual that slowly restores trust, empathy, and moral imagination. Seasonal rituals thus function as rehearsals for civic life. Just as societies once lit fires to mark the solstice, today we can perform acts of ethical attention that illuminate darkness in the social fabric, reminders that light, generosity, and hope are communal achievements, not merely personal experiences.

The relevance is immediate. Economic inequality demands generosity and advocacy. Racial and religious divides demand tolerance and empathy. Political polarization demands engagement and ethical imagination. In all these realms, the principles embedded in Christmas—drawn from solstice traditions and Abrahamic moral codes—offer guidance. Ethical attention to the Other, practiced seasonally and deliberately, eventually becomes a civic habit. Healing the nation is not a single act but a series of small, cumulative practices: sharing resources, listening across differences, protecting the vulnerable, and actively participating in community life. These are the same virtues that sustained human societies through long winters and precarious times, centuries before the commercial trappings of modern holidays emerged.

The story of Christmas, then, is a story of civic possibility. It tells us that light can emerge from darkness, that generosity is stronger than greed, that community is more resilient than isolation, and that the vulnerable are essential to the moral health of society. These lessons transcend theology: they are part of humanity’s shared moral imagination. To celebrate Christmas as it was meant to be celebrated—ethically, communally, civically—is to perform an act of moral restoration. It reminds us that empathy, tolerance, and civic duty are not abstract ideals but practical obligations. In a nation so rent by difference, these seasonal rituals offer a roadmap for ethical engagement, one small act at a time. Though Christmas is the lens here, its lessons—the renewal of communal bonds, the practice of generosity, the cultivation of empathy—are universal, inviting all communities to participate in the ethical work of society.

No society is too divided, no darkness too deep, for human generosity, moral courage, and civic imagination to take root. The ethical and civic heart of Christmas, once recovered, can illuminate a path toward a more compassionate, cohesive, and just America. Each act of care and attention reveals the enduring power of shared moral practice and the pulse of civic life, offering the promise that, even in our most fractured moments, the light of ethical and civic consciousness can return, as reliably as the turning of the year itself.