International interest in Balochistan’s mining sector is once again in the spotlight. According to the Chief Secretary of Balochistan, Shakeel Qadir Khan, global attention is no longer limited to the massive Reko Diq copper-gold project. Companies from the United States and the United Arab Emirates are now exploring mineral-rich districts such as Chagai, Washuk, and southern parts of the province, particularly for antimony a rare and strategically important mineral used in defense, electronics, and renewable energy technologies.

By Basit Zaheer Baloch

The so-called provincial administration presents these developments as a turning point. Barrick Gold’s investment in Reko Diq, officials argue, has opened doors for further foreign participation. The project is expected to begin production by 2032, with claims that Balochistan will receive a 25 percent share, amounting to nearly one billion dollars annually without direct provincial investment. Infrastructure promises accompany this vision: a Rs94 billion water pipeline, upgrades to the Taftan Quetta railway line, and broader economic activity across the region.

On paper, this sounds like progress. In reality, for many Baloch people, it reopens deep wounds.

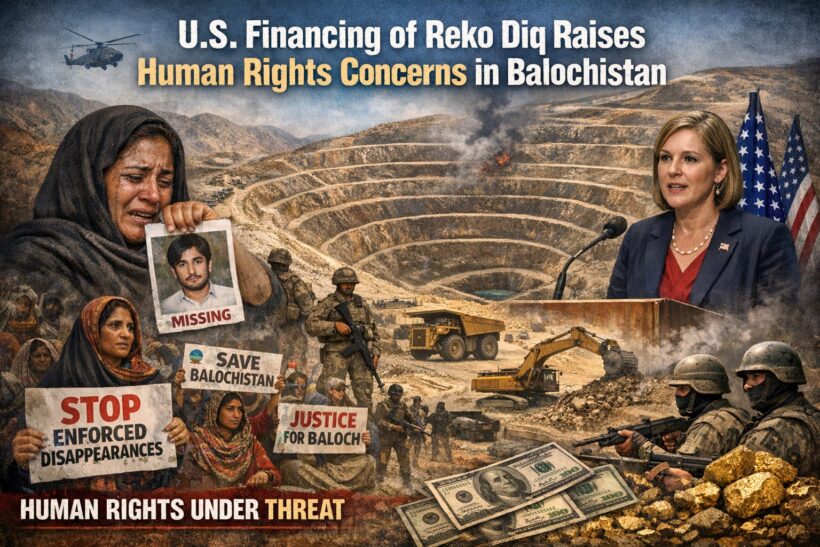

Recently, the U.S. Government, through Chargé d’Affaires Ms. Natalie Baker, announced approximately $1.25 billion in financing linked to the Reko Diq project. This announcement has been celebrated by state officials as a sign of international confidence. However, for the Baloch population, it feels like yet another moment when the world chooses minerals over human lives.

Balochistan remains one of the most militarised and politically suppressed regions in South Asia. For decades, Balochistan has witnessed enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings, torture, mass arrests, and military operations that have devastated entire communities. Thousands of families continue to search for missing loved ones, holding photographs instead of answers. The killing of Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti under General Pervez Musharraf was not an isolated incident, but part of a long history of silencing dissent through force.

Today, the situation has grown even more alarming. Baloch women and girls face harassment, threats, and disappearances, while peaceful activists and student groups are routinely targeted. Movements such as the Baloch Yakjehti Committee (BYC), which demand nothing more than the recovery of missing persons and basic justice, are met with arrests and intimidation. In such an environment, the claim of “consent” for large-scale mining projects becomes deeply questionable.

International law is clear: all peoples have the right to self-determination and permanent sovereignty over their natural resources. These principles are meant to prevent exploitation under coercive conditions. Yet in Balochistan, natural wealth gold, copper, gas, and now antimony is extracted under heavy military presence, with minimal consultation and little visible benefit for local communities. Agreements reached in fear cannot be called fair; they are imposed, not negotiated.

The Chief Secretary speaks of governance reforms, merit-based appointments, restored schools, improved vaccination coverage, and fiscal discipline. While these administrative measures may show some improvement on paper, they do not address the core political and human rights crisis. Development statistics lose meaning when people cannot speak freely, when protest is criminalised, and when entire districts live under constant surveillance.

This is why U.S. and other foreign investments in Reko Diq raise serious ethical concerns. Without binding human rights conditions, transparency, and independent monitoring, such financing risks turning international actors into silent partners in repression. What is labelled “investment” by governments is experienced by many Baloch as endorsement of their suffering. The implicit message is painful but clear: Balochistan’s minerals matter more than Baloch lives.

Development without justice is not development; it is exploitation. Investment without accountability becomes complicity. Silence in the face of widespread abuse contradicts the very values of human rights and dignity that global institutions claim to defend.

The Baloch people accept development. They reject development imposed at gunpoint. They reject progress that advances while daughters disappear, elders are killed, and voices are silenced. True development must be rooted in consent, justice, and respect for human dignity.

The international community, including the United Nations, must take the human rights situation in Balochistan seriously. Independent investigations into enforced disappearances, violence against women, and suppression of peaceful movements are urgently needed. UN bodies and human rights observers must be granted access to the region. All foreign-funded projects, including Reko Diq, should be evaluated against strict human rights standards to ensure they do not fuel abuse.

There can be no lasting peace without justice. And without justice, no mining project no matter how large or profitable can ever bring real progress to Balochistan.

Basit Zaheer Baloch, Political worker, Human Rights activist, and writer.

Facebook: basit.zaheer.94