Muradabad is a village in Islampur, Jamalpur. During the Liberation War of 1971, the Pakistani occupation forces established a camp at the local police station, just three kilometers from this village. The invaders would abduct innocent women from the village, bring them to this camp, and subject them to inhumane torture. Unintentionally, a ten-year-old boy named Md. Liakat Ali Mia became a direct witness to this horrific abuse.

It was toward the end of June 1971. Liakat could not recall the exact date or day. On that particular day, he was walking along a village path toward the market to sell milk, passing by the Pakistani army camp. Seeing the bucket of milk in his hand, a guard at the camp gate took him inside. After taking the milk, the soldiers handed him a ‘two-anna coin’. They also gave him some meat and bread to eat. However, his gaze shifted toward a room on the northern side of the camp. There, he saw three naked women being brutally and sexually assaulted by the Pakistani soldiers. That stigmatized moment of history was etched into the depths of his young heart as a memory of profound pain- one that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

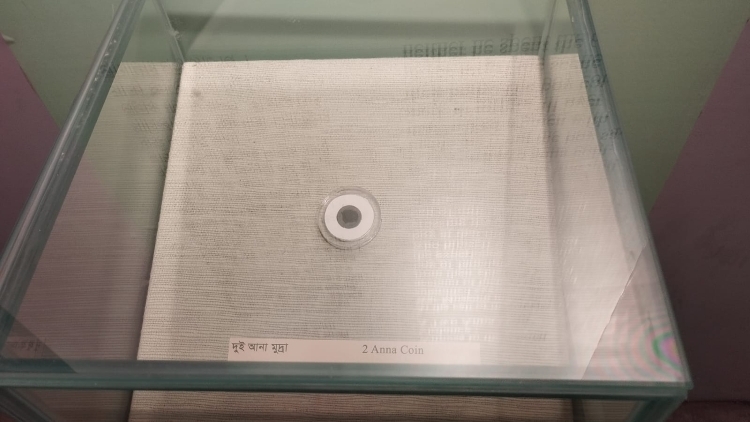

A silver ‘Pakistani two anna’ coin gleams in a glass showcase in the corner of Gallery-4 of the Liberation War Museum. Photo: Courtesy of the Liberation War Museum.

As a witness to the inhumane cruelty against women by the Pakistani forces, Liakat Ali Mia carefully preserved that two-anna coin for decades. Later, he and his son, M. Zillur Rahman Jamil, handed it over to the Liberation War Museum’s archives. At the time of the handover, Jamil was a brilliant tenth-grade science student at Jila Bangla Sugar Mills High School in Dewanganj, Jamalpur.

Regarding this, Jamil said, ‘One day, I asked my father about the story behind this Pakistani two-anna coin. While telling the story, he recounted the horrific scene of the Pakistani forces’ sexual violence against women that he had witnessed during the war.’

His father told him, ‘Most people in the village were not highly educated, but they risked their lives to help the freedom fighters (Mukti Bahini) to punish the invaders. Villagers would gather at the porch of the Mia house to listen to the heroic tales of the freedom fighters on the radio. Majnu, the eldest son of the Mia family, had joined the war to free the country, which was a matter of great pride for them. On the other hand, a few wealthy Maulanas from the village had joined the Razakar force (collaborators). These Razakars would abduct village girls and deliver them to the Pakistani camp. Because the camp was at the police station, the village women lived in constant terror of losing their honor.’

According to Zillur Rahman Jamil, his father used to hide his sisters (Jamil’s paternal aunts) in a hole in a sugarcane field to protect them from the invaders. However, it didn’t take long for word about the girls of the Mia household to reach the camp. Consequently, the Pakistani forces surrounded the Mia house in late June. Although the women were not home that day, two young boys, Dulal (8) and Ador (9), were present. The soldiers were about to attack them when a Razakar living near the Mia house intervened. He convinced the soldiers that everyone in that house was ‘pro-Pakistan.’ Because of that lie, the two children survived.

The Coin in the Museum

Today, this silver-colored two-anna coin shines inside a glass showcase in Gallery-4 of the ‘Liberation War Museum’ in Agargaon, Dhaka. It stands as a witness to the abuse of women by Pakistani forces in 1971.

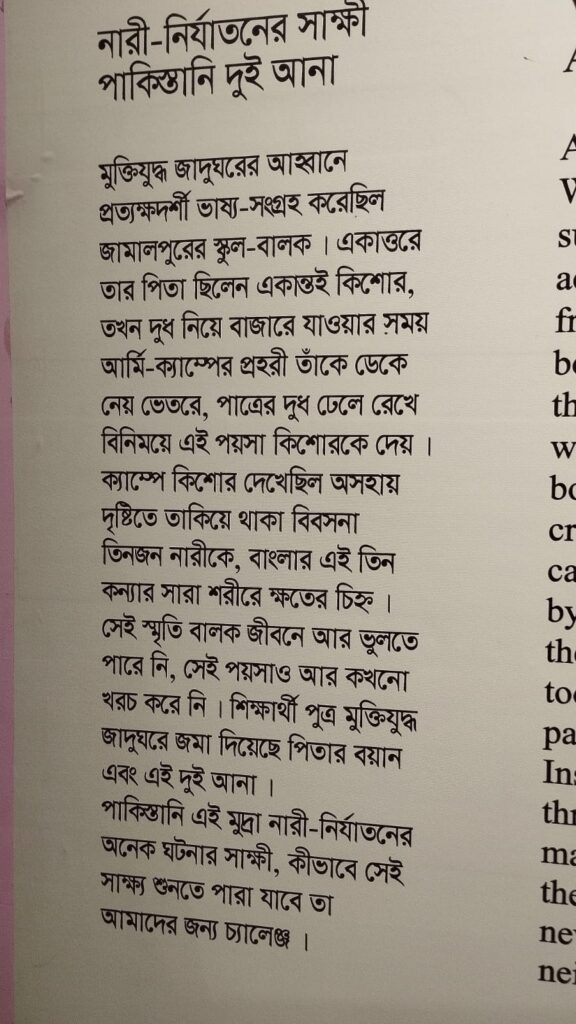

The story of the coin is written on the wall of the museum. Photo: Courtesy of the Liberation War Museum.

On the adjacent wall, a caption reads: ‘Following an appeal from the Liberation War Museum, a schoolboy from Jamalpur collected the testimony of an eyewitness of ’71. In 1971, his father was just a teenager. While going to the market with milk, a camp guard called him inside. They kept the milk and gave the boy this coin in exchange. Inside the camp, the boy saw ‘three naked women’ staring helplessly. There were wound marks all over the bodies of these three daughters of Bengal. The boy could never forget that memory. He never spent that coin. His student son has now submitted his father’s testimony and this two-anna coin to the museum. This Pakistani coin is a witness to an incident of violence against women; hearing that testimony is a challenge for us.’

Mofidul Hoque, a Trustee of the Liberation War Museum, stated that the museum launched a program to collect eyewitness accounts across the country through its ‘Mobile Museum.’ We encourage children through network learning. A teacher voluntarily joined this program and spread the call to every school in their area. They told the students, ‘You were born long after the war, but there are many people around you who saw it. Their experiences are invaluable.’ Through this, we have found many voices,’ he said.

He added that they have collected about 60 thousand such stories, one of which is the story of this two-anna coin. ‘The father had never been asked about this painful experience before. His son wrote to us about the coin and the abuse his father witnessed. The most significant part is that the father never spent the money; he kept it. It is a cruel story. Metaphorically and literally, his painful emotions were tied to that coin. There are often no formal records of the Pakistani forces’ atrocities against women, especially when the cruelty was so severe that the victims were not in a state to speak. Many were even rejected by their families upon returning. When we received the letter, we contacted them. The father and son came to the old museum in Segunbagicha to hand over the coin. We have displayed it to inform the younger generation about the harrowing history of 1971.’