In recent years, heat has stopped being just a number on a thermometer and has become something we can literally see at the atomic scale. In 2025, an international team led by Yichao Zhang used an ultrahigh‑resolution electron microscope to capture how individual atoms in a quantum material wiggle because of heat, reaching a resolution better than 15 picometers, far below the size of an atom.

The experiment focused on two‑dimensional materials such as tungsten diselenide, which can be peeled into atom‑thin sheets and stacked like transparent paper. The researchers placed two of these sheets on top of each other with a tiny twist angle, creating a moiré superlattice, a larger geometric pattern that does not exist in either layer alone and that strongly alters the material’s electronic and thermal behavior.

To probe this strange landscape, the team used an advanced technique called electron ptychography, which combines a finely focused electron beam with powerful reconstruction algorithms. This “quantum camera” allowed them to measure how sharp or blurred each atomic spot appears in the images and, from that blurring, extract the average amplitude of thermal vibrations for every atom as a function of its position in the moiré pattern.

In solid‑state physics, heat is described as collective vibrations of the crystal lattice called phonons, the vibrational cousins of photons. Twisting two layers into a moiré superlattice gives rise to new collective modes known as moiré phonons, and theory predicted an especially soft, low‑energy family of them: phasons, subtle shifts where the moiré pattern itself slides relative to the underlying atoms.

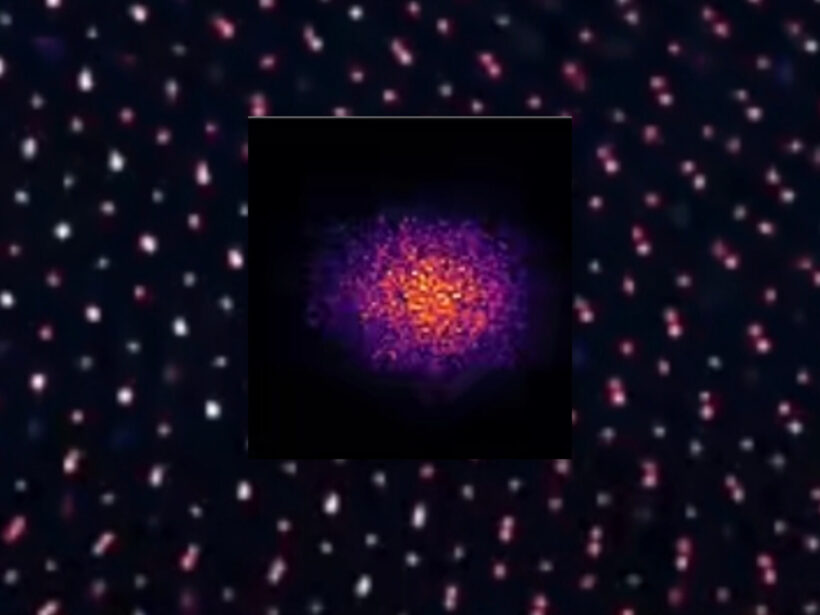

The key result of the study was the first direct imaging of these moiré phasons, showing that they dominate the thermal motion in low‑angle twisted bilayer tungsten diselenide. By correlating the microscopy data with molecular‑dynamics simulations and lattice‑dynamics calculations, the researchers showed that vibrational amplitudes grow near solitons and AA‑stacked regions of the moiré, revealing a hidden branch of phonon physics that had previously existed only in theory.

A simple way to picture this is to imagine two transparent grids placed one over the other and slightly rotated, producing a large‑scale interference drawing: that is the moiré pattern. Now imagine that each square of the grid is an atom and that heat is how much each square shakes; in some parts of the pattern the shaking is strong, in others it is mild, and the distribution is highly structured.

The new imaging technique is like having a camera so sharp that it can resolve not only the position of each square but also how fuzzy its outline becomes due to its thermal motion. Analyzing millions of these tiny blurs, the team identified a new kind of collective tremor, the phasons, in which the entire interference pattern slides like a ghost image over the underlying grids while each atom keeps its local order.

Readers who want to see the raw science can look up the paper “Atom‑by‑atom imaging of moiré phasons with electron ptychography,” available on arXiv and in journal form, along with its open data sets. Popular‑science outlets such as ScienceDaily and Phys.org have published accessible summaries and striking images that show these atomic vibrations in false color, turning the invisible dance of heat into something visually tangible.

This is more than a beautiful picture: directly imaging atomic vibrations opens a new path for engineering how heat and electrons flow through ultrathin materials. Controlling phasons and other moiré phonons could lead to ultra‑efficient chips, more robust quantum devices, and nanoscale components that manage heat in ways classical materials never could.

The work also illustrates the scientific moment we are living in, where exponential advances in microscopy, computation, and algorithms converge. Tools like electron ptychography turn once‑abstract concepts into directly observable phenomena, pushing us into a peak period of discovery in which the quantum behavior of matter is not just calculated but literally imaged, atom by atom.