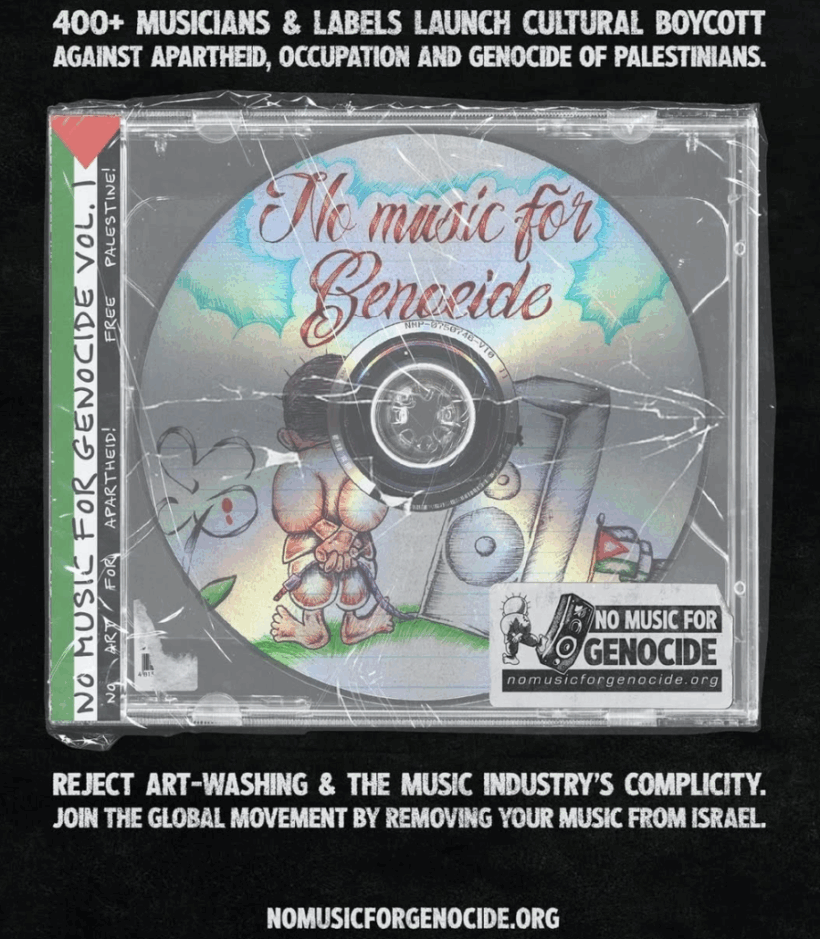

The “No Music For Genocide” campaign is not an isolated gesture of indignation; it is a cultural intervention that reopens an ancient and urgent question: what do we do with truth when it appears before us? Do we make it grow as light, or do we instrumentalize it as shadow? More than 400 artists and labels have decided to geoblock their catalogs in Israel —or to remove their work entirely from certain platforms— to deny cultural normality to a state accused of genocide in Gaza and of apartheid practices against the Palestinian people.

It is not an arbitrary punishment of the public, but a conscious political decision: to place truth squarely in front of us, validate it with radicality, and act accordingly, interrupting the symbolic circulation that makes the intolerable appear “normal.” The campaign, launched in mid-September 2025, calls for georestriction in Israel of musical catalogs, for coordinated actions of visibility —such as the 48-hour takeover of Radio AlHara in the West Bank— and for inspiration from the South African precedent of cultural boycott. Among those who have joined or aligned publicly are Massive Attack, Primal Scream, Björk, Japanese Breakfast, MIKE, Arca, Faye Webster, Fontaines D.C., and hundreds of others, with labels and collectives supporting the movement.

Naming the platforms is no minor detail, for in them the ethical dilemma materializes. The boycott targets the DSPs (digital service providers) that dominate global listening: Spotify, Apple Music, Deezer, Tidal, YouTube Music, and Amazon Music. The most widespread measure is geoblocking in Israel, a technical lever already familiar to artists in other geopolitical contexts and which today serves to deny cultural legitimacy while the crime persists.

In parallel, a more radical strand of the boycott has chosen to withdraw from Spotify globally, igniting debate around the nearly $700 million round led by Daniel Ek, Spotify’s CEO, in the European military intelligence company Helsing. For many musicians, continuing to monetize on Spotify means that a portion of the value of their art feeds into technologies of war. Thus, bands like Massive Attack have requested their music be removed from Spotify worldwide while also demanding geoblocking in Israel on other platforms. Other artists and labels denounce the “moral burden” between the streaming economy and high-tech military complexes.

Precision about “linkages” is necessary: at present, there is no public evidence that Apple Music, Deezer, Tidal, YouTube Music, or Amazon Music directly finance Israeli arms companies; the spotlight currently falls on Spotify due to its CEO’s investment in European defense. For the other platforms, the ethical reproach lies in their commercial operation in Israel and in their contribution to the cultural normalization of a context where a “digital apartheid” has been documented, restricting Palestinian connectivity and circulation of content. In Gaza and the West Bank, blackouts, network throttling, and moderation biases requested by state units make the musical public sphere even more asymmetrical. Hence the accusation of “not being complicit” has two layers: cutting the economic/symbolic flow to those linked to war, and refusing to decorate with playlists an architecture that silences victims.

Here the philosophical discussion begins to weave in: the validation of truth, and the refusal of complicity, are articulated in acts that seek to establish a new sense in the public sphere. Each repetition of the denunciation is not redundant but a strategy to frustrate forgetting, combat complicity, and force culture to confront its own limits. Thus the question of truth is not abstract: can culture be neutral in the face of crime? Is it possible for truth to survive its instrumentalization as product, as commercial cover? The boycott directly confronts this dilemma, betting on an ethics in which memory is active and taking sides is no longer a peripheral option but an indispensable necessity.

At this point, the dilemma articulates a crucial philosophical tradition that spans millennia and arrives in the present. For Socrates, truth is emancipation —the task of philosophy is to give birth to truth and not conceal it, even at the cost of personal and collective discomfort. For Machiavelli, truth becomes an instrument: what matters is effect, not truth itself. Socrates challenges his fellow citizens not to fear discomfort or the risk of condemnation if it is in the name of just pursuit; the philosopher becomes an uncomfortable witness.

In contrast, Machiavelli teaches rulers that truth can and must be hidden, simulated, and dosed according to opportunity, and that the survival of power justifies betrayal and shadow. If Socrates’ gesture is that of the artist who boycotts and defies normality, Machiavelli’s is that of power that instrumentalizes culture to perpetuate the status quo: both vectors collide in each act of geoblocking, each withdrawn playlist, each decision to make visible or remain silent.

Yet the discussion on truth and complicity becomes more complex. Hannah Arendt warns that the greatest threat to freedom of opinion does not lie in overt censorship but in the dissolution and substitution of facts: when “alternative facts,” carefully edited, impose themselves on public judgment, lies cease to be exceptional and found an opaque world where memory is the battlefield. For Arendt, the commitment of the intellectual and the creator is to defend the factual space that makes judgment possible. In the context of the musical boycott, the withdrawal of works functions as a radical affirmation of the existence of intolerable events and as a gesture that refuses to let culture serve as backdrop for the normalization of crime.

Noam Chomsky carries this demand into the terrain of contemporary political and intellectual action: committing to truth means, by definition, disturbing power and taking sides. It is not enough to recount facts; one must expose the active manufacture of consensus that perpetuates injustice. The “manufactured consensus” is the structural danger of our globalized media. By renouncing neutrality, boycotting musicians assume —as Chomsky insists— the task of dirtying discourse, staining the comfortable superficiality of consumption, and provoking the questions that dominant culture silences.

Byung-Chul Han adds another indispensable edge: neoliberal positivity and transparency do not equate truth with visibility. We live under the paradigm of “everything must be shown,” yet in that ocean of data and access, human life, pain, and structural violence are perfectly dissolved, aestheticized, appropriated by metrics and market flows. Culture, when it conforms to this logic, loses its edge and all denunciation risks emptying itself into simulacrum. The boycott —with its withdrawal and its strident gesture of absence— interrupts that flow, restores negativity, opacity, the power of discomfort against uncritical circulation.

Slavoj Žižek would say that the true ethical act is not enunciation but interruption, the cut. It is not simply a matter of choosing “what I like or not”; it is daring, through discomfort to oneself and others, to break the circuit of enjoyment and self-justification that sustains systemic violence. A genuine musical boycott produces that fissure: it denies micropleasure, rests in the negative gesture, and turns absence —silence— into a political question. Art then ceases to function as anesthesia and once again unsettles consciences.

Walter Benjamin brings the final warning: every denunciation, every memory, can be captured, aestheticized, and commodified, even the most radical critique. If politics is aestheticized, it loses all emancipatory capacity and becomes spectacle. The pedagogy of “No Music For Genocide” is therefore also a struggle against its own co-optation: it seeks to preserve the force of the gesture, to force the weight of discomfort to remain, and to insist that art is not mere “decoration” and its silence not just another product.

Consistency —material, discursive, strategic— thus becomes the core of the campaign’s philosophical and political value. To withdraw or block music where it belongs; to argue, without reducing to a hashtag, the relationship between the streaming economy, investment chains, and human suffering; to articulate with local networks of memory and resistance. In this way, truth ceases to be a formula and reincarnates as a practice of collective intervention. Each reiteration about complicity and legitimacy, far from being a trap or circle, is another knot in the weave, another tension and reminder that the battle for memory and truth requires insistence, slowness, discomfort, and community.

The musical boycott, understood in this way, is not merely rejection: it is genealogical intervention, collective praxis, and a living dispute over the function of culture. It is not about winning a war or erecting culture as the ultimate judge of politics, but about preventing —as far as possible— forgetting from winning the peace. When hundreds of musicians withdraw or block their works, when the public is left without playlists and asks “why?,” when platforms must answer for their flows and executives, something more than a symbolic gesture occurs: truth, validated head-on, once again lights where there was shadow. And that light is not mere metaphor; it is memory, it is questioning, it is the threshold of another conversation. The task of culture, in times of devastation, is to remind us that humanity is not an algorithm of infinite repetition, but the fragile and urgent capacity to choose truth —even when it hurts— over the comfort of shadow.