“The 21st century does not belong to oil. It belongs to those who control lithium, copper, graphite and rare earths.”

Oil dominated the 20th century through wars, dictatorships and corporations that shaped modern history. Today humanity enters a new era. Climate change is no distant threat but a burning reality that ignites forests, melts glaciers and displaces millions of people. The 21st century will be defined by the energy transition, that global race to replace fossil fuels with electricity, green hydrogen and clean technologies. Yet every solar panel, every wind turbine and every battery depends on minerals that are not traded in Wall Street or Davos, but lie buried in salt flats, mountains and deserts of the Global South.

From the year 2000 to 2100 there will be no single dominant resource. Instead, a shifting board where lithium, copper, graphite, nickel, cobalt, manganese and rare earths compete for the crown of indispensable raw material. Whoever controls these inputs will control the value chains of electric mobility, renewable energy and heavy industry. The map of power has already changed and will continue to do so. This is not science fiction or antimatter. It is hard data showing where the fate of the planet will be decided.

Block 1. Lithium, the White Gold of Transition

The lithium triangle formed by Chile, Argentina and Bolivia holds nearly 60% of global reserves. Chile controls 36% and in 2023 exported more than USD 8.6 billion in lithium compounds. Argentina is projected to become the world’s second-largest producer by 2030, with more than 20 projects in Jujuy, Salta and Catamarca that could generate over USD 10 billion in annual exports. Bolivia guards the largest treasure in Uyuni with 21 million tons of reserves, though hampered by technical barriers and only USD 100 million in pilot exports by 2024.

The international price jumped from USD 10,000 per ton in 2020 to USD 70,000 in 2022, stabilizing near USD 25,000 in 2024. By 2030 global demand will quadruple, driven by over 30 million new electric cars annually and by storage systems requiring more than 3 million tons of lithium each year.

Block 2. Copper, the Backbone of Electrification

Every electric car requires 80 to 100 kilos of copper—three times more than a conventional vehicle. The International Energy Agency projects copper demand to rise 50% by 2040, surpassing 35 million tons per year compared to today’s 25 million. Chile and Peru together produce over 40% of global copper and more than 8 million tons annually.

Prices averaged USD 8,500 per ton in 2024 and could exceed USD 12,000 by 2030 unless new mines are opened, according to BloombergNEF. The electrification of grids, batteries and wind turbines depends on copper as much as lithium. A single 3 MW wind turbine requires more than 4 tons of copper, and every kilometer of transmission line consumes 2 to 3 additional tons. The electric future will be copper—or it will not be.

Block 3. Rare Earths and Invisible Power

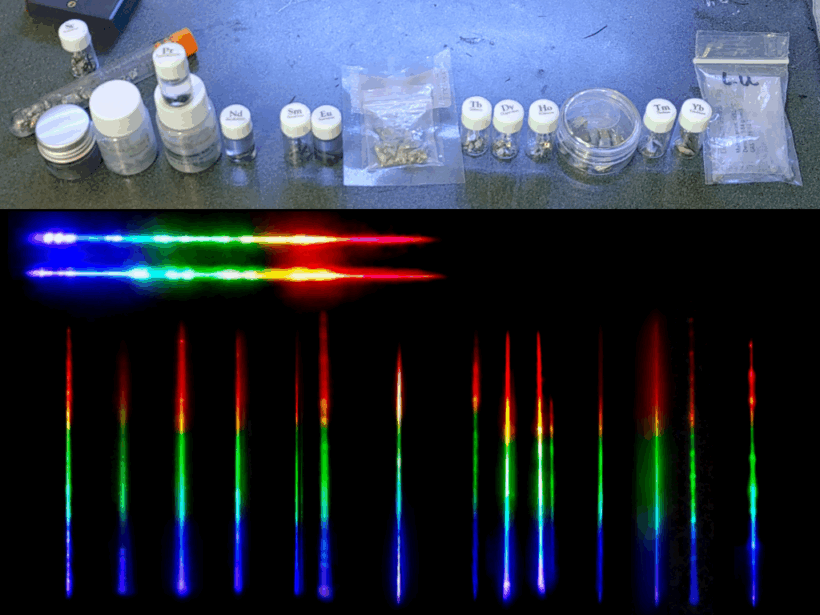

China controls more than 60% of global production and 85% of refining of rare earths. Neodymium and dysprosium are essential for manufacturing permanent magnets in wind turbines and electric cars. The European Union declared these raw materials strategic and irreplaceable in 2024.

A wind turbine magnet can contain up to 200 kilos of rare earths. The United States is trying to restart production in Mountain Pass with investments exceeding USD 1.5 billion but still relies on China for 74% of its imports. Japan, Korea and Europe spend over USD 10 billion annually on rare earths, indispensable for their tech industries. By 2050 demand could triple to over 400,000 tons per year.

Block 4. Nickel, Cobalt and Graphite, the Battery Minerals

Graphite is the main material for anodes, with more than 70% of processing concentrated in Asia. Nickel and cobalt increase the energy density of NMC batteries, though LFP chemistries reduce that dependency. Congo supplies 70% of the world’s cobalt—over 120,000 tons per year—under harsh labor conditions, with an estimated 40,000 children in artisanal mining.

Indonesia is the largest nickel producer, with more than 1.6 million tons in 2023 and exports exceeding USD 30 billion, a key input for electric vehicles. The combined trade value of nickel, cobalt and graphite exceeds USD 60 billion annually. By 2040, demand for nickel in batteries will rise 300% and for graphite 500%, according to the IEA.

Block 5. Green Hydrogen, Promise and Struggle

Green hydrogen today costs USD 4–6 per kilo, far above natural gas or coal at USD 1–2 per kilo equivalent. Projections aim to cut costs to USD 1 per kilo by 2050 through massive subsidies and renewable expansion. Europe has pledged to import 10 million tons by 2030, plus another 10 million from third countries.

Chile, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Australia compete to lead exports. Chile plans to produce 1 million tons by 2030, worth more than USD 15 billion. Saudi Arabia will invest over USD 8.4 billion in the NEOM project, set to produce 600 tons daily from 2026. By 2050 the global market could exceed USD 2.5 trillion—20% of the world’s energy mix.

Block 6. The Geopolitical Map of Power

China controls more than 70% of lithium refining, 80% of solar panel production and 80% of batteries. The United States launched the Inflation Reduction Act with USD 370 billion in subsidies to attract clean industry and produce over 1 million EVs annually with regional inputs.

Europe relies on import contracts and environmental regulation but depends on external suppliers for more than 85% of its critical minerals. Africa and Latin America emerge as suppliers of lithium, copper and cobalt, though without yet controlling the value chain. Competition is fierce: whoever dominates refining and export routes will set the pace of the energy transition.

Block 7. Water and Renewable Energy, the Hidden Inputs

Lithium extraction from salt flats requires millions of liters of brine evaporation. In the Salar de Atacama, companies pump over 2,000 liters of brine per second—63 million cubic meters annually. Green hydrogen production requires freshwater and renewable electricity at scale.

Projects in Chile, Morocco and Namibia already face conflicts over water use in arid zones. A 1 GW electrolysis plant can consume more than 9 million cubic meters of water per year. The hidden resource of transition is not just minerals but water and sunlight turned into strategic inputs. Without them, lithium and green hydrogen remain empty promises.

Block 8. The Environmental and Social Cost

In Argentina, Kolla communities denounce lithium projects without prior consultation, despite legal obligations on indigenous consent. In Congo, thousands of children work in artisanal cobalt mines under extreme risk of collapse and toxic exposure.

In Chalkidiki, Greece, protests halted gold and copper projects due to groundwater impacts. Tourism in Greece or Chile clashes with mining expansion that consumes water and territory. The energy transition risks repeating the history of extractivism if environmental respect and social justice are absent. The paradox is stark: clean energy in Europe or Asia at the cost of ecosystems and communities in the Global South.

Block 9. Projections 2030–2050

Global lithium demand will increase sixfold by 2050, exceeding 3 million tons annually. Green hydrogen could supply up to 20% of world energy in 2050, with more than 180 million tons. OPEC estimates oil and gas will still account for over 40% in 2040, though in decline.

The battery market will exceed 3,500 GWh in 2030, worth USD 400 billion. China will continue to dominate most of the battery and refining value chain.

Europe will meet only 10% of its lithium needs with domestic production by 2030. The United States aims to cover 25% through bilateral agreements with Latin America and Australia.

Block 10. What Is at Stake

Lithium powers electric mobility. Copper sustains grid electrification. Rare earths move turbines and motors. Green hydrogen promises to decarbonize heavy industry. The dispute is not only technological but political.

The risk is a new colonialism disguised as green, where few win and many lose. The central question is whether the future will be a just transition with shared benefits or a repeat of past plunder under new flags and old logics.

Block 11. Closing Note

Summary: What will be most valuable (2035–2050/70)

- Lithium is key for mobility and storage batteries, with projected demand quadrupling by 2030 and multiplying sixfold by 2050.

- Copper is the backbone of electrification in grids, cables and industry, with demand projected to grow 50% by 2040.

- Rare earths are indispensable permanent magnets for wind turbines and EV motors, with demand expected to triple by 2050.

- Graphite, nickel, cobalt and manganese are secondary yet strategic minerals sustaining battery chemistry diversification.

- Water and renewable electricity are invisible but critical inputs for extraction and green hydrogen production.

Mineral / Input — Use / Importance — Demand Projection / Growth

- Lithium — Mobility and storage batteries — Demand ×4 by 2030 and ×6 by 2050

- Copper — Electrification of grids, cables and industry — Demand +50% by 2040

- Rare earths — Permanent magnets for wind turbines and EV motors — Demand ×3 by 2050

- Graphite, nickel, cobalt, manganese — Battery chemistry diversification — Secondary but strategic minerals

The energy transition demands minerals. Solar panels, wind turbines, electrolyzers and batteries all consume copper, lithium, nickel, cobalt, graphite and rare earths. Demand will multiply between 2030 and 2050, turning these inputs into strategic assets and targets of geopolitical rivalry.

1.For its role in electrification, copper ranks first.

2.For electric mobility, lithium is irreplaceable.

3.For wind generation and motors, rare earth magnets are the crucial piece.

Technology may alter trends, but no serious projection (IEA, UN, WEF) foresees a transition without these minerals.

In conclusión, the raw material of excellence will not be one. It will be a set: lithium, copper, rare earths, nickel and graphite—alongside water, solar and wind energy. Whoever controls their extraction, refining and value chains will control the 21st century.

The 21st century will not have a single dominant resource like oil in the past.

It will be an era of multiple strategic raw materials shaping the history of energy and geopolitics. Lithium, copper, graphite, cobalt and rare earths are the keys to transition, but also the chains that may trap nations in a new cycle of dependence. The future will not be written with speeches but with hard numbers and political decisions. Clean energy can be a global pact of justice—or a repetition of plunder painted green. Humanity has until 2050 to decide whether to turn transition into hope or into condemnation.

Bibliography

- International Energy Agency, Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2024

- World Bank, Minerals for Climate Action Washington 2022

- BloombergNEF, Energy Transition Investment Trends London 2023

- ECLAC, Lithium in Latin America: Opportunities and Challenges Santiago 2023

- WEF, Critical Minerals and the Energy Transition Davos 2025

- UNCTAD, Commodities and Development Report Geneva 2024

El siglo de los minerales críticos. Del cobre y litio al futuro energético del planeta