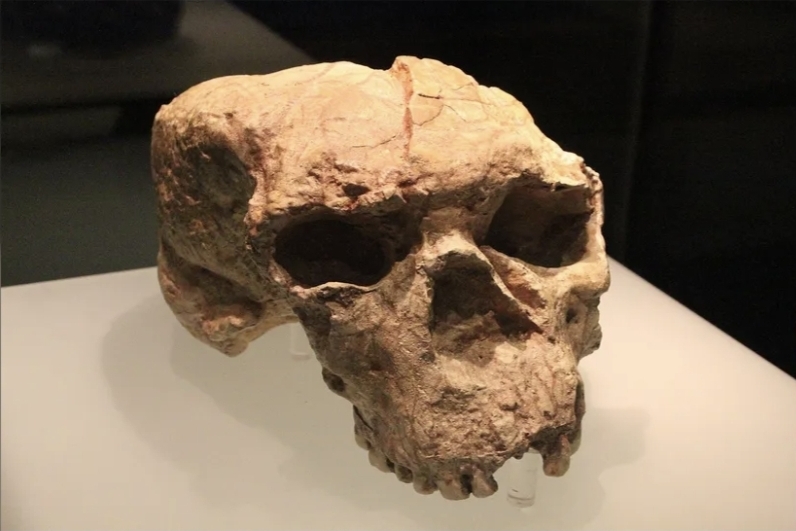

The digital reconstruction of the Yunxian 2 skull, discovered in Hubei in 1990 and dated between 940,000 and 1.1 million years ago, constitutes an epistemic event that goes beyond the merely archaeological. Precisely this week, an international team of paleoanthropologists published in the scientific journal Nature the article “Digital reconstruction of the Yunxian 2 skull reveals early diversification of Eurasian Homo lineages”, authored by María Martinón-Torres, Wu Xiujie, José María Bermúdez de Castro, and collaborators. There they explain how a fossil severely deformed by geological processes could be restored through a highly precise technical pipeline: high-resolution computed tomography, structured light scanning, virtual modeling, and systematic comparison with more than one hundred hominin specimens. What is decisive here is not the raw find, but the way in which the documented reconstruction returns an operative object to scientific debate, turning the skull not into a fossil corpse but into a reproducible morphometric reference. The merit is that this was not a speculative “retouch” but a critical restitution of geometries that allows the hypothesis to be subjected to rigorous scrutiny. The first scientific premise, therefore, lies in the trust earned by methodological transparency: a fossil shattered by stone acquires new life as a comparative node within a verifiable analytical framework.

The second premise stems from the comparative results: the combination of a low and elongated cranium with a remarkably high endocranial volume for its age, together with unique facial traits, places it far from the classic Homo erectus and draws it clearly closer to the clade represented by Homo longi, historically linked to the Denisovan lineage. From there arises the third premise: if Yunxian 2 truly belongs to this deep Asian lineage, then the divergence between the main human lineages—sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans—occurred earlier than conventional chronologies predicted, perhaps more than a million years ago. The fourth premise, however, reminds us of the vulnerability of the result: genetic evidence does not yet exist, and every morphological reconstruction rests on auxiliary assumptions. Put differently: the hypothesis is technically and conceptually strong, but epistemically provisional. Here science gains clarity, but not final certainty.

From these premises, questions that touch the foundations of our self-image emerge anew. Does Yunxian 2 prove that modern humans come from Asia? Rigour demands a negative answer. The origin of Homo sapiens remains firmly rooted in Africa, supported both by the density of fossil evidence and by the weight of genomic data. What this fossil does suggest is that humanity’s common trunk was less linear than imagined, and that Asia shifts from a passive periphery to a co-protagonist of evolutionary divergence. This finding compels us to distinguish it from two major historical theories. On the one hand, it does not imply a return to classical multiregionalism, which defended parallel and independent evolutions in different parts of the world converging on modern Homo sapiens; the genomic evidence of shared African ancestry and gene flow refutes that strong reading. On the other, it does not uphold the most rigid version of the African replacement model, conceived as a single sapiens expansion that displaced and extinguished all previous lineages without remainder. What Yunxian 2 brings to light is a third path: an indisputable African origin in terms of the appearance of our species, but coexisting with differentiated lineages in Asia and Eurasia that diverged earlier than expected and later interacted, interbred, or coexisted with the sapiens expansions. What emerges, in sum, is a form of “connected multicentrality”: recognition of Africa as cradle, but a rejection of exclusive hegemony, since Asia too preserves deep branches of the human tree.

In this regard, the next question—has the Out of Africa paradigm died?—finds a nuanced answer: no, what dies is the simplified version. The straight arrow of a single exodus is replaced by networks of waves, mixtures, and returns. The finding challenges strong multiregionalism, because it preserves a common African root, and it challenges strict replacement, because it shows that archaic lineages were not blind alleys but historically significant interlocutors. The metaphor of a single-trunk tree no longer suffices: we must think instead of a reticulated, entangled forest.

Why, then, does a single reconstructed skull matter so much? Precisely because it belongs to what paleoanthropologists call the “Muddle in the Middle”: the confused Middle Pleistocene, that ambiguous period in which species, traits, and chronologies appear to melt into uncertainty. There, a well-restored and methodologically transparent fossil acts as a conceptual calibrator: a clear piece that reorders entire blocks of taxonomic interpretation. And at the same time, like every Popperian hypothesis, Yunxian 2 opens a field of predictions: if the longi/Denisovan lineage was already differentiated a million years ago, more fossils with comparable morphologies should be found and, ideally, biomolecules should be recovered that confirm deep divergences. The virtue of the hypothesis lies not in shielding itself, but in exposing itself to refutation; that is what makes it science, not dogma.

From the Kuhnian perspective, this is a fertile anomaly. A single fossil does not generate an immediate paradigm change, but it accumulates tension upon the dominant conceptual matrix. Science does not pivot on a headline, but gradually erodes narratives that proved too neat. Yunxian 2 does not instantly replace the canon, but it erodes the linear narrative and contributes to establishing a plural and interwoven vision of human origins. Its philosophical importance lies precisely in this fertile dissonance. And viewed through a Popperian lens, its strength lies in simultaneously brushing against the robustness of the African replacement model and of multiregionalism, by pushing the divergence backward in time and forcing us to reconsider established models. In this friction lies its value: not to innocuously confirm, but to problematize.

The Duhem–Quine warning operates with equal intensity: there is no reconstruction without theoretical assumptions. Every virtual restoration depends on deformation models, symmetry criteria, and reference corpora. Epistemological honesty resides in recognizing these auxiliaries, not in concealing them. The openness of the reconstruction to critique is what makes Yunxian 2 a scientific fact rather than laboratory echo.

All this reverberates in an anthropology of origins: if for centuries cultures have used biological genealogy as a founding myth to legitimize hierarchies, narratives such as the one emerging from Yunxian 2 destabilize any exceptionalism. The reticulated tree denies the possibility of an ethnicity “predestined by biology”: there is no hegemonic center, but a swarm of lineages intertwined. Consequently, science itself reveals its role as political narrative. When we say “where we come from,” we also speak of the present and its systems of legitimacy.

From an ethical standpoint, if Asia preserves deep branches of the human tree, then its fossil heritage and its communities must participate in the stewardship of that memory. Science is not the owner of the past but a guest, invited to negotiate with concrete cultural legacies. A plural humanity demands, in turn, plural research practices attentive not to repeat epistemic colonialisms under the disguise of unified narratives.

Recognizing the plasticity of the human tree, however, does not mean collapsing into relativism. Precisely because DNA is absent and morphologies are ambiguous, the bar of rigor must be raised. Provisionality calls for strong skepticism, not cynical dispersion. Replication, expansion of the fossil record, convergence of methods: only under these standards can we sustain a robust epistemology in the face of the seductive risk of novelty.

In conclusion, the following can be affirmed: first, that Yunxian 2 provides convincing morphological evidence of a deep human lineage active in Asia around one million years ago, akin to Homo longi/Denisovans. Second, that this chronology pushes back the divergence of our great lineages and dismantles the illusion of a single, late axis. Third, that the resulting image is one of reticulated, multicentered evolution, in dialogue between Africa and Asia. Fourth, that the hypothesis is strong but provisional, since neither genetic proof nor a comprehensive fossil sequence are yet available. Fifth, that the immediate philosophical effect is clear: to dissolve exceptionalism, to gain in plurality and humility.

The conclusion, therefore, is not the dogmatic substitution of one narrative for another, but the acceptance of a broader truth, woven in networks rather than straight lines. If Yunxian 2 withstands the tests to come, our shared history will be revealed not as a univocal epic, but as a braid of intertwined human branches. And of that braid, no one holds exclusive ownership: neither a region, nor a culture, nor a discipline. At times, a crushed skull does not only return an ancient face; it also teaches us to broaden our minds.