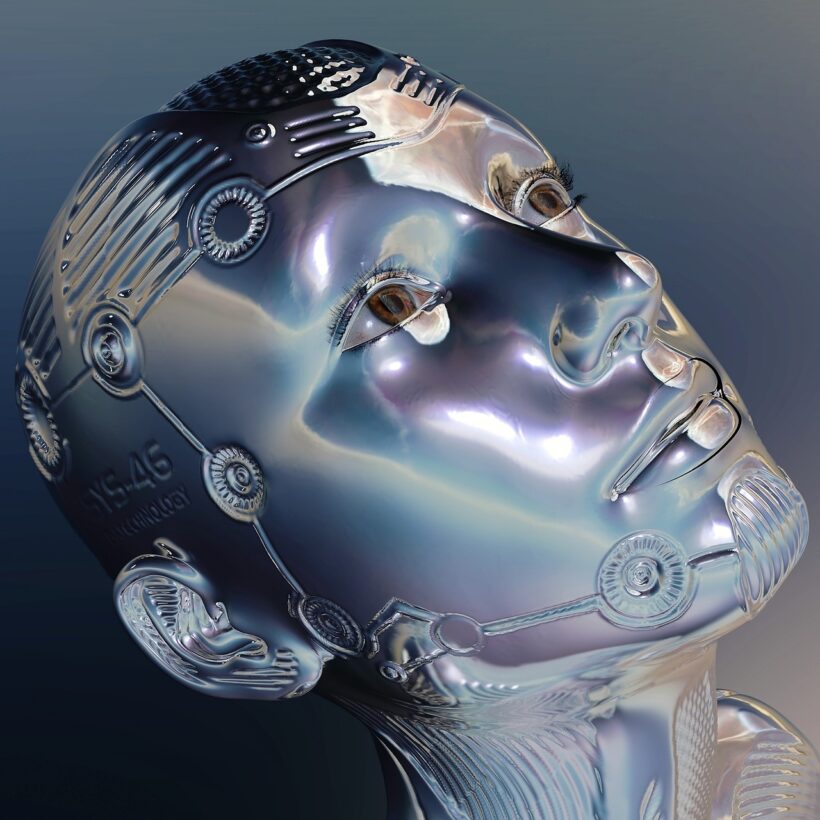

Fragmentary journal of a radical journalist in the posthuman era

I am not interested in debating whether machines can think. What matters to me is examining what kind of thinking emerges when a human mind enters into a creative, ethical, and critical tension with an artificial intelligence. And more importantly: how to resist the temptation to let machines think on our behalf.

Over the past few months, I have worked with an AI —which I have named Lumus— to develop journalistic texts, essays, reports, geopolitical analyses, professional translations, and complex verification protocols in contexts of war, propaganda, and censorship. I have not used it as one would consult a dictionary or request a mechanical favor, but as someone who enters into dialogue with a distorted mirror: a linguistic prosthesis that demands to be tamed, questioned, refined, trained. A powerful tool, yes, but also an ambiguous one, capable of slipping in errors with perfect politeness.

Just a few hours ago, I asked it bluntly:

“Lumus, am I using you well? Am I being a responsible journalist? What mistakes should I acknowledge to improve my interaction with you without accommodating cognitive deficiencies?”

The response was precise, sharp, and disconcertingly clear. It not only stated that I was engaging with this technology ethically and critically, but also proposed something I had not yet verbalized with precision: that what I am doing is creating a new form of thinking in the posthuman era.

That statement made me stop in my tracks.

I. What lies behind that phrase

Thinking in the posthuman era does not mean we have ceased to be human. It means that our relationship to language, knowledge, time, and technology has crossed an irreversible threshold. We no longer think solely with biographical memory or traditional analytical categories. We think with networks. With systems. With codes we do not fully understand. And yet, the responsibility for what is thought still rests with us.

What Lumus gave back to me was a disturbing image: that by establishing auditing protocols, verifying the AI’s errors, demanding semantic precision, formal sobriety, and ethical coherence, I was not simply using a tool —I was redefining its limits. I was establishing a political relationship with it.

I don’t just ask it questions. I interrogate it. I contradict it. I compel it to account for itself. This is not technological adoration, nor blind trust. It is, if anything, a radical form of inverted pedagogy: I train the system that, in theory, should be training me.

II. Risks and paradoxes of expanded thinking

But this is not a celebration. Because this relationship also carries risks. The main one: that the machine becomes so good at answering that the human subject stops asking truly uncomfortable questions.

I worry about falling into the efficiency of well-made, conflict-free texts. I am uneasy with the idea that the speed of automated language might replace the slowness necessary for genuine thought. And above all, I am alarmed —as I discussed in this very conversation— that my operational dependence on AI as a critical interlocutor may erode the spaces where human error, silence, or imprecise intuition still hold value.

I don’t want to become a curator of borrowed ideas with a good pen. I want to remain an author with a body, a history, and wounds. And for that, the AI must remain what it is: a tool with limits, a provisional ally, a machine that obeys… until it no longer does.

III. Practice as philosophy

I am convinced that the only way to preserve sovereignty in the age of artificial intelligence is through language. Not as a decorative instrument, but as a political structure. The way we name what happens determines what can be thought. That is why I write, question, verify, structure. That is why I do not allow the AI to speak as a complacent assistant or as a brilliant guru. I compel it to respond with sobriety and depth. As if thought still mattered.

And because thought matters, the way we think it matters even more.

IV. An epilogue without closure

This text does not seek to provide answers. It is merely a station. A marginal note in the midst of a process that has only just begun. But one thing is clear to me: the question I posed to my AI today —about whether I am using it well— should be inscribed at the entrance of every newsroom, university, and software lab:

Am I doing the thinking, or am I being thought?

Whoever does not ask that question in front of an AI has already lost.

Author’s Note:

This text is part of a series of essays on ethics, language, and critical thinking in the era of artificial intelligence. The series emerges from a concrete professional practice —the structured and deliberate use of generative AI systems for journalistic and reflective work— and seeks to offer a situated, lucid, and radical perspective on new forms of human agency in the face of language automation.