“My faith has helped me with my queerness and my queerness helps me in making my faith inclusive”

by Tashi Choedup

From the time I was a child, it was my faith that kept me grounded, and that gradually gave a sense of belonging to myself and to the rest of the world.

I was born into a Hindu family in October 1990, and I grew up saying that I will become a monastic. Of course, my naïve understanding of being monastic back then was not having a household life, living close to nature, praying and meditating. I wasn’t even thinking of it in terms of belonging to a particular religious order. My first access point to my faith was the religion that I was born into. Even before I began narrating my sexuality and gender identity, the first queer thing I began experiencing with and navigating through was my faith. I knew it was religion that gave me my first foothold to my faith, but I innately felt that religion wasn’t the source of my faith. The religious space that I was part of facilitated my practice and study. But how I did that practice and study, I believe, was my first significant queer expression/engagement. All the queerness that I rejoice in and celebrate was shaped and strengthened by my faith and its journey.

As passionately as I practiced Hinduism, I also engaged with other faith traditions that were introduced to me through some very kind teachers. Teachings of Christ and Buddha were two very significant ones among them. My continuous study with Buddhism helped me realize two things:

- What I was trying to read predominantly in Hinduism and other religions is exactly what I found in Buddhism.

- For the longest time I could remember, I deeply desired a sense of home, and my engagement with Buddhist philosophy helped to understand me that if I am not home with myself I am not home anywhere with anyone!

This brought me very close to my childhood aspiration of being a monastic and helped me realize that it is in the Buddhist tradition. Thanks to the kindness and generosity of my teachers that aspiration became a reality!

My feminist and queer friends knowing about my ordination as a monastic were happy with my happiness, but they also had questions and concerns, because in their world it is quite unusual for someone like me, a queer person with progressive liberal politics, to take vows and become part of a religious order for the rest of the life!

One of the popular questions was: What does becoming a monastic mean to my gender, queerness, and sexuality?

In Buddhism it is said that there are two kinds of believers: there are people whose belief is solely dependent on faith and there are people whose belief is based on faith derived from rational, logical inquiry and verification. And the latter is considered to be superior to the former. Thus by applying the rational mind, I am a homosexual celibate. My vow of celibacy is based on my sexual desire: if there would be no sexual/romantic desire, obviously I could not take such a vow of abstaining from it.

A part of this question is also about the necessity to abstain from sexual desire and become a celibate in order to have a deeper practice of one’s faith. I believe it is not the only path. As we are diverse and unique individuals, it seems unreasonable to have faith practices in any religion confirmed to one standard. In the past and contemporary times Buddhist practice was upheld and taught by different kinds of people including both lay and ordained. Buddha himself defined Buddhist sangha to be fourfold: monks and nuns, laymen, and laywomen. Scripture mention individuals who attained full-enlightenment being laypeople. For example, Khema, a disciple of Buddha and wife of king Bimbisara, was said to have attained enlightenment even before leaving the lay life. In my case, I was always drawn towards monastic life. Other than my faith, human rights work, and few friendships I cherish, there wasn’t much in my lay life with which I had a sense of engagement or belonging. The vows and the commitment I made are of course not free of struggle or easy to keep up with, but my awareness of life being rooted in monastic vows gives me the conducive conditions to practice my faith in the best way possible. This helps me to acknowledge and to keep up the struggle of engaging with my desires and abstinence. The novice vows I keep are the same for monks and nuns and to assert my non-binary gender identity I use the word “monastic” for myself. And “they/them” as pronouns.

And the second popular question is: What does Buddhism say about queerness?

In June 1997 in San Francisco, a meeting took place between His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama and a group of Buddhist lesbian and gay people. They wanted to seek clarifications from the Dalai Lama regarding his comments on homosexuals. After listening to personal stories of the group members, how they were subjected to discrimination on the basis of their sexuality, the Dalai Lama said:

“It is wrong for society to reject anyone on the basis of his or her sexual orientation. Your movement to gain full human rights is reasonable and logical. There is nothing wrong with people engaging in mutually agreeable sexual acts… it is unacceptable for anyone to look down on gay people.”

In that same meeting, the Dalai Lama also quoted from the text of a 14th century Tibetan master, Lama Tsongkhapa. In his text Lam rim chen mo – Treatise on stages of the path, Tsongkhapa states that sex between men is inappropriate. After quoting this, the Dalai Lama spoke about the possibility of looking at such prohibitions in the context of their time, culture, and society. He also said that:

“If homosexuality is part of accepted norms today, it is possible that it may be acceptable”.

According to the Dalai Lama, no single person can change these precepts and it should come through the discussions of sangha (religious communities) of various Buddhist traditions.

In his 2013 book titled The Heart is Noble: Changing the World from the Inside Out, His Holiness the 17th Gyalwang Karmapa has a chapter on gender in which he writes:

“Gender identities permeate so much of our experience that is it easy to forget that they are just ideas—ideas created to categorize human beings. Nevertheless, the categories of masculine and feminine are often treated as if they were eternal truths. But they are not. They have no objective reality. Because gender is a concept, it is a product of our mind—and has no absolute existence that is separate from the mind that conceives of it. Gender categories are not inherently real in and of themselves.”

The more I see the contemporary Buddhist teachers engaging with the issues of gender and sexuality and the growing number of queer Buddhist folks who are forging a healthy relationship between their queerness and their Buddhist faith at an individual level and also at a collective level, the more I am inspired and hopeful.

This hope is strengthened also by looking at all the amazing, powerful women Buddhist teachers (both lay and ordained) who play a significant role not only in making the Buddha’s teaching reach many more people (especially women) across the globe but also challenge the notions and practices of patriarchy within their religious communities. In 2011, Geshe Kelsang Wangmola became the first nun to finish her Tibetan Buddhist academic degree, which was denied for women before. Jetsunma Khandro Rinpoche, as one of the most popular female teachers, inspires many in and outside Buddhist communities. Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo, professor at the University of San Diego through the Jamyang Foundation, strengthens a large community of Himalayan nuns by supporting their education. A recent letter by Ven. Pema Chodron and a petition by Buddhist women (lay and ordained) demanded an investigation into an allegation of sexual misconduct by prominent monk Dagri Rinpoche. Both are examples of inspiring as well as difficult conversations taking place in Buddhist communities.

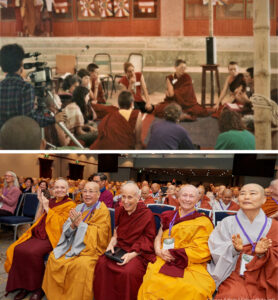

“These two pictures remind me that no matter how small the beginning of any journey towards an inclusive, just, equal world is, no matter how many obstacles we have to go through, the journey is always inspiring and transformative. The first picture shows the humble beginning of Sakyadhita in 1987 (copyright Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo, Sakyaditha), and they have grown as shows the second picture (copyright Olivier Adam). Sitting in the first row are Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo (far left), Ven. Karma Lekshe Tsomo (2nd from right) and Ven. Thubten Chodron (3rd from Right) who continue to be a source of inspiration in my faith and social justice practice. To see and know that gatherings like these are taking place to develop more skilful conversations of change is exhilarating and heartening.” – Tashi Choedup

In the Kalama Sutta, also called Buddha’s Charter of Free Inquiry, Buddha advises not to accept anything just because it is from scripture or tradition or your teacher, but to investigate and verify it before accepting it. In the spirit of that inquiry and in my personal experience I believe that it is possible for queer folks to engage and communicate with the religious community that I am part of, giving an opportunity of learning for each other. Over the last three years, I was part of a Tibetan Buddhist center in Bodhgaya, Bihar, India. It was comprised of a small community of resident members and a large community of short-term and long-term students. In my time there, for many people I was the first queer person they met, let alone the first queer monastic. It was confusing for some and intriguing for others. But one thing that we all shared and appreciated was the space for kind and genuine conversations. Currently, I am taking a break to study psychology. Nonetheless, thanks to technology, the conversations with the virtual Buddhist community continue while I am part of a diverse classroom in a private university in the south Indian city, Vishakapatnam, which seems to be a new learning ground for understanding how the mainstream responds to faith and queerness in combination.

Religion is meant to be a space of healing, where vulnerabilities and differences are met with kindness, love, and compassion.

All religious leaders need to realise that there is no “us and them” here. The struggle for equal rights is not just for the people who are marginalized on lines of gender, caste, race, class, sex, sexuality, religion, ethnicity, but for everyone. Whether people realize it or not: an inclusive world with equality, justice, kindness, compassion, and love benefits everyone. It takes away everyone’s suffering and makes space for everyone’s happiness.

Like one of the Buddhist saying goes, who doesn’t seek happiness, and who doesn’t want to be free of suffering? Buddha’s first noble truth was the “truth of suffering.” Suffering is pervasive all through our existence, one thing common across all living beings. Buddha went on to say in the fourth noble truth that there is a “path to complete cessation of suffering.” A path that is open and available for everyone. In a nutshell, suffering is the reality of life and so is the desire for happiness and the desire to be free from suffering; it is universal among all living beings. Buddhist practice – or for that matter any faith practice – is about helping and supporting each other in realizing that desire into a reality.

It is not just about religion being inclusive of LGBT people. It is about religion being inclusive of faith, faith that is professed by many different people, in many different contexts and realities, and some of them are LGBT people. Each person of belief brings to their religious community and space their unique experience and expression of the faith they embody. Each person only enriches and nurtures their religious community and all its members. Religious leaders need to actively facilitate inclusion.

I believe that my faith has helped me with my queerness and my queerness helps me in making my faith inclusive.

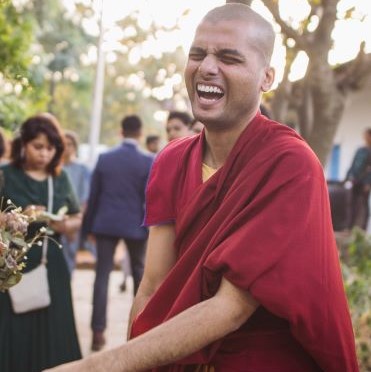

Tashi Choedup is a practicing Buddhist monastic, a non-practicing homosexual, and a performing queer person. While they engage in some human rights and interfaith work currently they are figuring out how to grieve the friends they lost to fascism, patriarchy, and heterosexual marriages.

This blog is part of a series for the Salzburg Global LGBT* Forum’s program on LGBT* and Faith. Read more here: www.salzburgglobal.org/go/LGBT/blog