The warehousing of asylum-seekers behind barbed wire encapsulates where ‘protecting borders’ leads.

As representatives of the European Union’s 27 member states came together on February 9th and 10th in Brussels, for a summit focused on war, the economy and migration, a number of leaders urged further ‘securitisation’, surveillance and border-hardening. The Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, argued that ‘fences protect all of Europe’.

Meanwhile Greece’s minister of state, George Gerapetritis, told the Financial Times the EU needed to agree on a ‘very strict’ approach, as his country was facing ‘persistent’ irregular migration. Notis Mitarachi, the Greek minister of migration and asylum, continued to advocate EU-funded fences on Twitter: those arriving irregularly to seek asylum should meet detention and deterrence rather than welcoming and support, he said.

What does this look like in reality for those arriving at the borders of Greece and the EU more generally? Since 2018 I have been visiting the island of Samos as a researcher, while working with and alongside various organisations supporting displaced people seeking asylum.

The situation there has been under-reported, compared with neighbouring Lesvos. Having spoken to a number of actors on the ground in the last few weeks, people continue to arrive, be pushed back, rendered homeless and placed in structures experienced as prison-like—with limited access to healthcare, education and everyday items such as shoes and clothing.

Dramatically changed

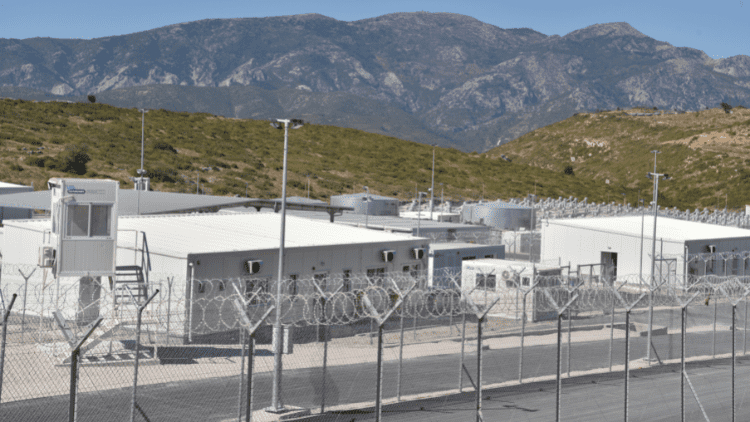

In September 2021 the situation on Samos changed dramatically with the closure of the open camp neighbouring the town of Vathy and the opening of the first Closed and Controlled Access Centre (CCAC) in Greece. Located in a remote area of the island, this limited access to Vathy—where much of the legal, social, medical and educational support was based—while a curfew prevented people from leaving the facility between certain times.

The CCAC currently has no resident doctor and access for nongovernmental organisations has been limited since last month: they are now required to complete all stages of the NGO registration process before access is regranted. Organisations previously providing medical support inside the camp are unable to do so.

New arrivals are subject to their own registration process, in which freedom of movement outside the camp can be restricted for up to 25 days. The bus into Vathy costs €3.60 and walking to it (unmanageable for many in the extreme conditions of winter or summer) can take two hours each way through the hills. This can lead to people being doubly trapped—by the barbed wire and the remoteness.

As one actor on the island told me, to describe the camp to those who have not visited often feels impossible: the layers of barbed wire, the airport-style security and the police riot buses, unimaginable until experienced. One camp resident, asked how it was, reportedly ‘burst out laughing and said: what, you mean the prison?’. Just coming and going, rather than being stuck there, engenders discomfort and a sense of surveillance.

Support denied

The opening of the CCAC was, according to the Greek government, supposed to mark the start of a new era in migration management in Greece, limiting access to the mainland while asylum cases were heard. Not only does this cruelly ‘warehouse’ individuals—many of whom will have been severely traumatised before and during their journey—out of sight and out of mind, but it also denies support asylum-seekers need and to which they are entitled.

I Have Rights, a legal actor on the island, said that at one point in 2022 it was impossible for even those requiring medical treatment on the mainland to secure a transfer. The organisation had been forced into months-long litigation on their behalf.

It then monitored a shift on the part of the authorities, with organised transfers to the mainland, of maybe 100 people a month, taking place—while still leaving asylum-seekers on the island in the dark as to what would happen to them and when. As of the end of January there were just over 1,000 people in the CCAC, whose capacity is over 2,000.

Paradoxically, having moved some people in this way, it is now possible for officials to tell a story about ending the ‘crisis’—how they have ‘cleaned up migration’. The number of people arriving last month was however far higher than in January 2022.

Indeed overcrowding of the camps and other structures on the island has, since 2015, been a symbol of this ‘crisis’ in Greece, and the CCACs have failed to put an end to it. Not only are humanitarian actors clear that arrivals remain high but legal organisations are also working beyond capacity, while those distributing clothing and other essential supplies are short on donations.

Producing precarity

For those who are granted asylum, the wait to receive residency documents has reached up to six months. This creates a high risk of homelessness: individuals who receive their asylum-acceptance documentation can only remain in the CCAC for 30 days—yet without the documents it is very hard to sign a housing contract.

These policies, then, produce precarity, often making people vulnerable rather than rendering them secure. The solution is not further prison-like structures, nor is it the building of walls and ensuring the troubled Frontex agency is focused on ‘protecting external borders’. The priority should be saving human lives, protecting the right to asylum and ending the pushbacks that vitiate it.