The fate of Europe is at stake in the French presidential elections next April. What will change if Jean-Luc Mélenchon is elected? Here is part of the answer. A long and in-depth interview that goes into theoretical and practical aspects of the struggle against capitalism. Moving away from the banal repetition of worn-out speeches. Proposing a path, and daring to discard old useless dogmas. Now and always, Machado’s verse: “You make the path as you go…”.

Interview by Ballast magazine – January 15, 2022

For more than ten years Jean-Luc Mélenchon has been advocating a “citizens’ revolution”. The formulation comes from Rafel Correa, elected president of Ecuador in 2007: during his inauguration, he presented it as a “radical change” aimed at leaving neo-liberalism behind. After gathering almost four million votes for his candidacy in the 2012 French presidential elections, Mélenchon, leader of the Left Front (“Front de Gauche”) co-founded the movement France Insoumise (“La France insoumise”): in 2017, seven million French voted for this candidate whose programme focused in particular on the “distribution of wealth”, “ecological planning”, the “exit from the treaties of the European Union” and the “end of the Fifth Republic” established by De Gaulle. In his youth, as a local leader of the Trotskyist formation International Communist Organisation, Mélenchon had joined the Common Programme promoted by the Communist Party and the Socialist Party, before leaving the latter to resurrect what he then called “the other left”. Now it is “the people” that his movement aims to mobilise. As part of this dossier entirely devoted to the different strategies for breaking with the dominant order, Ballast magazine went to meet Jean-Luc Mélenchon and published this fascinating interview.

Since 2009, you have been calling for a “citizens’ revolution”. This is a strategy that breaks with both the historical revolutionary model and the social democratic left. On what basis?

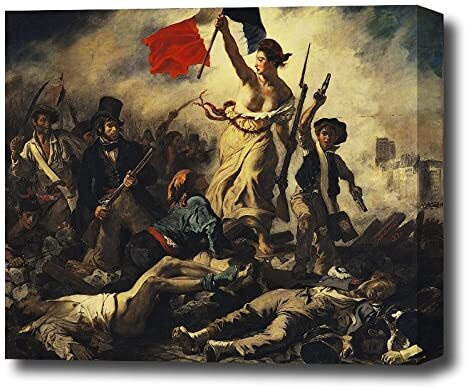

A strategy must have a material basis in society. Therefore, a revolutionary strategy must begin by answering the question: who is the revolutionary actor? The answers to this question determine the forms of organisation and action. I belonged for a long time to a school of thought for which wage workers were the exclusive actor of the revolution. So we went to meet them. We thought of action according to the place and organisation of the employees’ work. I take the example of the proletarian revolution because it is in this conceptual space that thinking about revolutions is most abundant. Since the victory of the Bolshevik revolution, we have had ample material for discussion. All the leaders of the workers’ movement have spoken, written or spoken on the subject. In contrast, in 1789, the study of the revolutionary process was not at the centre of the concerns of the revolutionaries themselves. Here and there, in one or two speeches by Robespierre or Saint-Just, we find a few considerations on the form of revolutionary action or on its developments. For example, Saint-Just’s famous statement (as always so precise): “Those who make half-hearted revolutions only dig their own grave”. Or his assessment: “The Revolution is frozen”(1). These are analyses of the state of the revolution that allow for strategic thinking. However, the role of the action of the sans-culottes sections has no place in the thinking of the leaders. But it is they who impose a triple power: monarchy and feudal system/assembly/sections. In the sections there is a form of truth about the revolutionary actor of 1789. Obviously, today, this actor cannot be the same as at that time, nor at the time of the proletarian revolution.

“The citizens’ revolution says everywhere: ‘We want to control’. Whether in Sudan or Lebanon, we are seeing these same internal dynamics.”

The general organisation of production, the division of labour, the involvement of the branches of activity: everything changes. Capitalism, and then finance capitalism, remarkably reduced the peasantry to its minimum expression. It was liquidated as a social class. This is no small development! In the past, a theory of socialist revolution could not be elaborated without taking the peasants into account. A considerable number of left congresses were held on the subject of the alliance with the peasantry. And when we say peasantry, we mean ownership of a means of production: the land itself. This was no small challenge! Today, we are facing a great social homogenisation. Liberals think that we are all connected and enveloped by the market. In fact, we are all dependent on collective networks and this dependence institutes a new social actor. This is the central thesis of what I call the “age of the people”. The revolutionary actor of our time is the people.

How do you define it, precisely?

The people is defined as all those who need the great collective networks to produce and reproduce their material existence: water, energy, transport, etc. The nature of the relationship with these networks, private or public, determines the form and content of the struggles, and in general of the revolutionary struggle. We demand access or denounce the impossibility of access to this or that network: thus, when we increase the price of fuel, we can no longer move, so we no longer have access to the networks. In France, that gives us the “Yellow Vests”. Another example: the increase in the price of public transport, that gives the Chilean popular outburst in 2019. We could multiply the examples with Venezuela, Ecuador or Lebanon. The closure of access to the networks acts as an intersectoral trigger for the whole pile of contradictions that, until then, each one of them had been going their own way. But there is also a counter-intuitive feature of this people: the more people there are, the more people there are, and at the same time the more individuation there is. The people of the citizens’ revolution are at the intersection of these two great ideas: the collective out of necessity, individuation out of a principle of reality. They are united in the desire for self-control. The citizens’ revolution says everywhere: “We want to control”. Whether in Sudan or Lebanon, we are seeing these same internal dynamics. At this stage, given the number of observations made since the beginning of the millennium, we can say that we have a phenomenology (2) of the citizen revolution.

What are the contours of this phenomenology?

We were able to identify four markers. First, the popular actor refers to himself as a “people”. It claims the term in its slogans. Secondly, this self-designation is always accompanied by symbols that reinforce the actor and his legitimacy. It is a question of visibility: yellow waistcoat, purple jacket, a colour, a flower. It is an anthropological factor that is stronger than it seems. It performs the same function as the uniform or the scarification. Thirdly, the self-proclaimed people systematically mobilise the national flag.

Is this to be understood as a form of nationalism?

No. We can even say that it has nothing to do with that.

The vast majority of the extreme left, however, analyses it in this way.

I invite my comrades on the extreme left to tear down the wall they themselves have built. The national flag is not synonymous with chauvinist nationalism.

That is a confusion. I challenge them to find a people’s meeting with revolutionary scope where the national flag is not present, from Sudan to Latin America. The people take the national flag and say to the leaders: “We are the country, not you”. It is another way of saying “Everything is ours”. It is a democratic and “dégagist” symbol (Go away, all of you!). The French Revolution of 1789 shouted in Valmy “Long live the nation” instead of “Long live the king! It is both a claim and a very political assertion of identity: the nation is the sovereign people. The same is true of the Paris Commune against the Prussians. By its content and its demand for citizens’ sovereignty, the process of the citizens’ revolution calls into question the legitimacy of those in charge. It is a phenomenon of “transcreation” (3) of the revolutionary process, passing from the social to the democratic terrain. Leon Trotsky had well described this in the conditions of the proletarian revolution. Basically, in revolutions only one question is asked: “Who exercises power?” That is why the citizens’ revolution presents itself as a dual power. That of the roundabouts versus that of the state. Finally, the social identity of the ruler is enough to sum up the society that is being configured.

You claim the national scale as a space for social transformation and seek to build an emancipatory “national-popular” identity, in the sense of the communist Antonio Gramsci. You don’t only see this patriotic feeling…

The nation is today the horizon of popular sovereignty. We can dream of other transnational horizons, but these are non-existent now. Democracy cannot be thought of only in abstract terms, without material reality. Democracy has its possibility of being massively exercised inscribed in the nation-state, now, as we speak. The patriotic sentiment I am calling for is this: it is linked to the republican idea, to the idea of popular sovereignty as the cornerstone of the nation. In France, more than elsewhere, it is easy to identify the national project with our countryside. We have a flag and an anthem that belong to a popular revolution. Our motto says “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”. The nation, in our country, comes from the Republic, not the other way around. This means that being French is not a religion, a skin colour, or even a language. The French nation can welcome creolisation (4) because its unity is based on principles. Moreover, we find national symbols in all the great recent moments of popular power in France: the French Revolution, of course, but also the Paris Commune or the Resistance and Liberation. It is sometimes difficult to get away from a distorted image of events.

Let’s take the Paris Commune as an example

The entire extreme left celebrates it. Karl Marx considered it “the political form finally found which made it possible to achieve the economic emancipation of labour”. It was a citizens’ revolution! The communards wanted to control everything. Otherwise, my thesis is that there have only been citizens’ revolutions. They used different methods and presented different programmes according to the level of development of the productive forces. It is necessary to move away from a mechanistic version of Marxism in which the proletariat necessarily fulfils the destiny of the development of the productive forces, as a kind of simple midwife of history whose party is the forceps. This explanation of the revolutionary process is far too incomplete. Moreover, there is not even a description in Marx of what a revolutionary process is! The only time he speaks of it is to compare revolution with a natural phenomenon, a volcanic eruption. As a counterpart, for a long time our camp has taken the 1917 revolution as an archetype. This has led to an overestimation of the importance of the party. I don’t think so. The key moment of this revolution is the last-minute discussion between Lenin and Trotsky about who will strike the blow. The party, Lenin said. He fears the conciliators around him, who swear by “socialist democracy” in relation to the rulers. The All-Russian Congress of Soviets, says Trotsky. The October Revolution is the expression of a democratic legitimacy: that of the soviets. For me, that is the fundamental moment!

What do you have to reproach the Leninist conception of the party for?

“The Future in Common” is a transitional programme: it breaks with the present society without saying what society it intends to establish, relying on history to answer the question.

Its success came from the Bolshevik Party’s victory in the Russian Civil War. But, initially, it is in fact a citizens’ revolution. What did the Russians want in 1917? They wanted the war to stop. They do not understand why the leaders do not put an end to a conflict that is impossible to win or lose. They no longer want to die for nothing. The triggering event of the Russian Revolution was the three consecutive days of women’s demonstrations, against the advice of all the revolutionary parties. The collapse of the Cossacks, who were sent to shoot them, caused, by a domino effect, the collapse of the Tsarist state. The Bolshevik party will finally win the day only because it is the only one, from one end to the other, that wants to stop the war. Then the Russian revolution itself descended into civil war when the Bolsheviks decided to dissolve the Constituent Assembly. This is not a simple little question. You have to read the writings of Rosa Luxemburg. She understands that the process of democratic agitation is a condition for the duration and achievement of the revolution. The Bolsheviks believe that party leadership is enough. This design had been very well criticised by Trotksy already in 1905. He calls it “substitutionism”: the party replaces the class, the central committee replaces the party and the general secretary ends up replacing the central committee. That is exactly what happened. This is also the cause of the break-up of the Tours Congress in France. You have to read Léon Blum’s speech. What does he say? That he is in favour of the seizure of power “by all means, including legal ones”. He also says that he is, “of course”, in favour of the dictatorship of the proletariat. So what differentiates him, as a socialist, from those who will become communists? Only one thing: the way the party is run. In my opinion, the far left remains captive to a revolutionary mythology that is not at the heart of political events: barricades, one-off armed clashes between the haves and the mass of the disinherited. But it never happened that way. On the other hand, re-reading all revolutions in the light of the criteria we have established in the context of the analysis of the citizens’ revolution allows a better understanding of the reality of a revolutionary process.

So you go back to which revolution?

Even in the 14th century with Étienne Marcel, we can detect these mechanisms! To describe the internal dynamics of citizens’ revolutions, two concepts borrowed from Trotskyism are useful. First, there is the mechanism of the “permanent revolution”. The revolutionary process produces an autonomous driving effect: “Since we did this, why wouldn’t we do that?” Then there is the phenomenon of the transcreation of social demands into democratic demands, or vice versa. That is why citizens’ revolutions lead to constituent assemblies. To continue, borrowing from Trotsky, one could say that “The Future in Common” is a transitional programme: it breaks with the present society without saying what society it intends to establish, relying on history to answer the question. This is not a propaganda ploy. It is an alignment with the real dynamics of citizens’ revolutionary processes.

And what is the fourth characteristic of the citizens’ revolution?

Anonymity. No one is allowed to represent others. There is no decision-making centre. Any mandate is immediately revocable. This may also be the fatal difficulty of this kind of movement. This characteristic is related to the high degree of connectedness that is also detected there: everyone has a smartphone. Recall that the tax on WhatsApp exchanges triggered the popular rupture and revolution in Lebanon in 2019. This omnipresence of the digital network has been consistently identified since the citizen revolutions in the Maghreb. This does not mean that digital technology is causing the revolution. The tool is invested by the reality of the networked world, it is the tool that expresses itself through tools.

You speak of “fatal difficulty”. Unlike a large part of the radical left, which is concerned with democratic horizontality, you see the leader as occupying a strategic and progressive function. Why?

“Many Venezuelans in the neighbourhoods discovered politics with Chávez on television and ended up creating neighbourhood councils.

There is a democratic role for the leader. The tribune puts into words the ideas of others. He represents them in the gallery. And often, hearing one’s own ideas, experiences, affections pronounced in an articulate and intelligible way of speaking produces a significant effect of catharsis. The tribune’s speech will make visible the shared character of what we thought was personal. It moves from the individual to the collective. The leader’s action can lead to a setting in motion and thus to a popular reappropriation of politics. Take the archetype of the left populist leader: Chávez in the 2000s. Many Venezuelans in the barrios discovered politics with Chávez on television and ended up creating neighbourhood councils. Contact with the leader had an increasingly profound effect on democracy. Distrust or denial of this phenomenon stems from a view of the political struggle as disembodied. But it is the other way around. There are no ugly affects on the one hand and the pure world of rational ideas on the other. Affects and ideas are two aspects of the same reality. Affections are the ideas in motion in each individual. The affective relationship with the leader is not necessarily an obscurantist and authoritarian fanaticism. It can also be a way for committed individuals to represent the collective force with which they identify. And in this case, it is a powerful democratic engine. In fact, all organisations are identified through a leader. But we never finished paying for the crimes of the cult of personality that was seen in Stalinism and Maoism…

To respond to this set of characteristics and evolutions, how does one get from the party (the Left Party) to the movement (La France insoumise), as a form of organisation?

By groping, from our materialist analysis of the new conditions of revolutions, of the “era of the people” and of the phenomenology of the citizens’ revolution. It remained to be understood how its victory would be possible and what the points of support could be. The mode of organisation depended on the material conditions of existence and organisation of the revolutionary actor himself. The era of the party corresponded to the era of the railway, landline telephony and the printing press. The newspaper is at the heart of the party. It is he who tells the truth or provokes the spark. It must build, make events comprehensible and unify the proletariat on the right line and the right strategy. The newspaper assumes a management organ which decides what it contains. It prints a particular rhythm, daily and, as a result, delayed by a day with respect to important events. Its dissemination is based on the railways. The party corresponds to a class organised and hierarchical by work, concentrated in specific places – the factories – connected by the newspaper and the railway. Against that, the enemy had its own ideological apparatus, its own organisation, its own centralisation: the foreman, the parish priest. But from now on, the new social actor has a different organisation and above all a new interconnection made possible by digital technology. It is composed not only of the working proletariat, but also of the unemployed, workers, pensioners and students. Now, the political struggle has almost instantaneous streaming videos. On our side, we have developed a mobile application: “Action Popularice”. The platform is the movement and the movement is the platform. This is an unprecedented historical situation: the political centre is connected individually to each of its members and the members of the movement are connected to each other horizontally. The movement corresponds to the form of the actor, and he has the means of this form. It expresses itself fully through the digital platform.

Does the movement allow for greater ideological diversity among activists?

Our line is action. It is the action that federates, not the theory. Whether you are a Marxist or a Christian, a Muslim or a Jew, it doesn’t matter to the movement. What matters is what we do together. Full stop. Our approach here is similar to the syndicalist tradition of trade unions, federating through mandates. That is why we no longer believe in the Bolshevik form of the “vanguard” party, which will always be a substitute.

Marxism and anarchism have always called, despite differences in temporality, for the disappearance and destruction of the state. It is a slogan you never take up again. You are even a firm supporter of it. Why is that?

Certainly, the state today is the organisational structure of a social model and its preservation. That there is a desire to do away with the state in its present form does not shock me. What I have a problem with is that nobody says what should be put in its place, because we need a great collective tool for the implementation of decisions: this can only be the state. Let’s take ecological planning. How do you want to undertake it without a state? On the other hand, I intend to discuss the unique place of the state machine in the decision-making process.

You project the image of a centralised Jacobin.

“That you want to do away with the state in its present form does not shock me (…) Let’s take ecological planning. How do you want to undertake it without a state?”

Yannick Jadot (leader of the ecologists in France) branded me a “red-green Jacobin dirigiste” when it comes to ecological planning. He then ended by saying that a “State deciding the orientations” was needed to do so. That is not my version. I believe that ecological planning and its objectives must come from municipalities, trade unions, cooperatives and even business organisations, since we are creating a mixed economy, not a fully socialised one. Of course, the National Assembly will also have a role to play in the process. But not as the techno-structure that imposes everything. I am in favour of the extinction of this particular form of state. And even more so of the State built by Macron: it is the worst version of the State. It is atrophied in its sovereign functions and, moreover, denies its specificity by entrusting the management of central administrations to executives from the private sector. I am still allergic to recitations of the Gironde. But they have led us to rethink the relationship between the form of the state and the institutions from the Corsican case. Let us even say that we are starting from scratch. When Corsica appoints three autonomist deputies out of four and elects twice in a row an assembly with an autonomist and separatist majority, even if you love the republican and revolutionary idea of the unitary state, you have to ask yourself. Faced with such a result, what should you do, deploy force? It is not possible. Send in troops? I will never do that. Because if we do, we will have already lost. The experience of New Caledonia proves it. So let us take note: France is no longer a unitary state from the point of view of the organisation of its administration. French Polynesia has its government; the territory of New Caledonia does not correspond to any comparable structure; Martinique has one territorial assembly, while Guadeloupe and Reunion have two. No one can pretend to build the France of the 21st century without taking this into account. So, for the Corsicans, I am ready to accept the autonomous status provided for in Article 74 of the Constitution.

In the early 2000s, Subcomandante Marcos asserted that “the centre of power is no longer in the nation states”. That it no longer made sense to “conquer power”. Is this the reason why, despite your well-known interest in Latin American progressive experiences, you never talk about the Zapatista experience in Chiapas?

First, I must remind your readers that this interest is explained by the fact that it is in Latin America that the chain of neoliberalism has been broken, and nowhere else in the world. Secondly, it is true that I know less about the Zapatista experience. I was first interested in the formation, in Brazil, of the Workers’ Party [in 1980, editor’s note]. It was the result of a front of small parties and gave rise to replicas all over Europe. Syriza in Greece, Izquierda Unida in Spain, Die Linke in Germany and, in France, the Front de Gauche (Left Front). This model has spread, unlike the Zapatista model. Although I admit that it has been able to fertilise libertarian forms here and there, especially within the “tsarist” movements (from the French “ZAD: zone to defend”): it is a revival of the once extremely powerful anarchist current, whether in Spain or in France. The Marxist victory there was not as total as they say.

But why, since your Trotskyist youth, have you turned your attention to the mass formations and not to the more marginal experiences of secession, of autonomy?

I tell you frankly: I am not criticising these experiences. Let everyone go their own way. In any case, it fertilises the global space. I knew the revolutionary struggle in that form in which everything depended on the definition of one – and only one – line and one – and only one – victorious strategy. That is no longer my conception. I believe in another mechanism, “intersectional” in a way. First, building or relying on cultural hegemony with blurred edges: they end up forming large plates that articulate with each other and then produce a kind of emergent property, a desire for achievement, on which the revolutionary strategy is based. So, in the context of the current presidential campaign, I’m not saying anything negative about the others, except for the social democrats, but that’s within anyone’s reach (laughs). I think everybody is expanding the plate they are standing on. Let’s take an example that will seem very far away: Montebourg (PS, former minister of Hollande). Well, it’s not like that. When he advocates sovereignty, he fuels the critique of globalised capitalism, which only works on delocalisation and the lengthening of production chains. This is positive, despite my criticism of the profoundly unsustainable nature of his recent comments on migrants. Second example: Jadot (environmental leader). He is in favour of protectionism. Very good. Protectionism is impossible within the framework of the European treaties. So you have to choose. But your statement contributes to the hegemony of our issues. Unlike the Zapatistas, I believe that state power must be won through elections. This can make it possible to make decisive progress in people’s conditions of existence. Both from the angle of the belly and from the head. Only the powers of the left spread education, which raises the level of understanding and consciousness in society. I believe in this and refuse to give up this conquest.

The conquest of state power itself has two divergent lines within the emancipation movement. Yours, electoral and non-violent, and the one that promotes physical confrontation with the forces of capital and the state. You have always proclaimed your hostility to violence. However, the yellow waistcoats have led more than one citizen to say to himself that, in the end, only violence makes it possible to be heard…

“… violence isolates the revolutionary process, dividing it (…) But I add: you will never find me barking with the dogs (…) I refuse to indulge bourge bourgeois fear.”

My role is to repeat, in fact, on the basis of the experience of our comrades in Latin America, that revolutionary violence leads to failure. Of course, there is the Cuban exception. But all attempts at reproduction failed and this story ended with the death of Che. But first, I draw my lesson from the struggle against Pinochet: if the best of us fall with weapons in hand, and it is always they who disappear first, only the least active will be left to lead the revolution. The MIR, of which I was a sympathetic member in France, had heroic fighters and they died in appalling proportions. However, in my opinion, individuals are fundamental to history. When, in the context of a revolution, you are left with only bureaucrats whose only aspiration is to see everything solved, whatever it takes, you no longer have revolutionary strength. The militants who were willing to risk their lives were also those who knew how vital it is for revolutionaries to be among the people like a fish in water. That said, I distinguish between two things: violence as a revolutionary strategy and violence that arises during episodes of struggle. And I agree with your observation: yes, people have said that smashing is the only thing that pays. Because this is what happened with the Yellow Vests: in the end the government paid ten billion euros. But it was not a thought-out or theorised strategy. The violence has been sporadic. So I stand by my position. Above all, because violence isolates the revolutionary process, dividing it. When violence breaks out in demonstrations, we no longer come to demonstrations with prams and children. There is also the withdrawal of women. But, the presence of women en masse is a central element of the citizens’ revolution. But I add: you will never find me barking with the dogs. I cannot stand the call to condemn those who are designated as violent. I refuse to indulge bourge bourgeois fear. Violence is first and foremost that of the masters. Does the bourgeoisie condemn social violence? The plucked-out eye? That is why I have not criticised the ZAD on this ground either. I have the same reasoning with regard to Cuba. I do not believe in the single party at all: in my eyes it is a very ineffective form of popular government. We need contradiction. Besides, it is not Marxist to imagine a society without contradictions. However, I assure you that Cubans have welcomed, cared for and protected our comrades. So, I repeat everywhere: I will criticise Cuba, if necessary, as soon as the United States of America lifts its embargo.

In 2014, during a tribute you paid to Jaurès, you described ecosocialism as the doctrine that should guide the next century. However, it has been discovered that this notion is no longer mobilised. Why?

That is true. I find that the word “socialism” introduces confusion. You have to spend hours saying what it is and what it is not.

Because of the Socialist Party?

In France, yes, and when you go to countries that lived under the authority of the Warsaw Pact and the USSR, it’s unpronounceable. Of course, I have no problem with the concept; I’m even an heir to it. But to inherit is also to project oneself. Today, I prefer to describe myself as a “collectivist”. The public mind has massively integrated the idea of the common good. Even young people who are not on our side claim to be green. This is a colossal difference from the 1990s, when you couldn’t say the word “capitalism” without everyone laughing. This is a considerable advance. This spontaneous collectivism corresponds, in my opinion, to the crisis situation resulting from climate change. I found the analysis of this crisis made by Paul Servigne in his book, “L’Entraide” (Mutual Aid). It is true that he is from the anarchist tradition and not from the “popular left”. But I often recycle myself with anarchist authors. Their scathing criticisms help me to think with glee.

Is this the reason why, when founding the Left Party, you reclaimed the libertarian heritage “in your own way”?

“I often recycle myself with anarchist authors. Their biting criticisms help me to think with glee”.

I claim it and I believe in it! Servigne’s message is essential: if we enter the crisis with the mentality of liberal society, it will be worse. Hence the word “collectivism”: it aims to develop the alternative “All together or every man for himself”. This word does not seem to me to contradict ecosocialism. It is a “bus-word”, whose method of use I borrowed from Paul Ariès – who put the term “degrowth” into circulation. I started to try out the word “collectivism” in the National Assembly: they booed from the right side (laughs). Sometimes they tell me that “collectivism” sounds even worse than “socialism”: I make the opposite bet. It fits well with a certain zeitgeist. And since it hasn’t been used for a long time, the word is ripe for a comeback! My role is to transfer the embers to the new hearth. We pull the embers out of the ashes and resume the flame war a little further. In this sense, we can even say that we save the embers.

You are used to saying that a company cannot operate on the basis of a permanent general meeting. Does this mean that representative democracy is the end of emancipation? Can we not conceive of more direct and less parliamentary forms of democracy?

This is a debate that is raised in every revolutionary sequence. It is clear that we cannot limit ourselves to representative democracy as it is practised. In La France insoumise, we have provisionally decided to say that it will be up to the newly elected Constituent Assembly to think about the next institutional system. There are two possible visions of the Constituent Assembly: revolutionary or avant-garde. In other words, take note of the popular outcome or proclaim in advance what regime it will have to give birth to. We have to take care of two things: guaranteeing a stable institutional system and allowing the people to intervene at any opportunity. This permanent possibility is the aim of the RIC (citizens’ initiative referendum) and the recall referendum, which we are proposing. The discussion we have there was also impossible in the 1990s! You can’t imagine what a victory it is to have brought the idea of the constituent assembly and permanent popular participation into the public debate. We are beginning to reconstitute a collectivist hegemony. However, there are 67 million of us in this country: we will not be able to vote by a show of hands in the manner of the Swiss cantons of yesteryear or to repeat the practice of traditional village assemblies. Modern tools can influence this debate. The question of compulsory voting will also be raised.

You are in favour of it, aren’t you?

Yes, free from the age of 16 and compulsory from the age of 18. And taking into account the blank vote. And if there are 50% blank votes, the election is null and void. In Ecuador, they experimented with new modalities. The Europeans are used to going to the four corners of the world to explain how socialism should be done, when they have been unable to implement it in even one country of the European Union! I am therefore confident in the initiatives that will emerge.

You have recalled your defence of the mixed economy and you regularly evoke the “financial” dimension of capitalism. What is your horizon: to abolish the capitalist mode of production in France, or to limit it as much as possible in a globalised economy?

When I speak of financial capitalism, I don’t mean the financial dimension of capitalism, but capitalism in its current form. Capitalism does not exist in general, but only under given historical forms. Since the 1980s, we have lived in a particular type of capitalism where finance capital rules the rest. So I assume the anti-capitalist dimension of what I have to do. But “L’Avenir en commun” (The Future in Common) is a transitional programme. It does not propose the abolition of private property, although it clearly breaks with the society of neoliberalism. The rest is not written. But it clearly opens up the possibility of an economic society that is based more on collective ownership than on private property, more on planning than on the market, and more on needs than on supply.

The economist Frédéric Lordon has been engaged in a work of anticipation. He imagines La France insoumise in power and predicts: it will not last two weeks in the face of the European Union and finance. “It will be a speculative storm whose strength cannot be imagined. […] It will be 1983 times five hundred”. Therefore, he sees only two eventualities: “submit” like Tsipras or launch a “war at all costs” against capital. What do you say?

I will quote a phrase of Trotsky picked up by Chávez: “The revolution advances under the whip of the counter-revolution”. I will be in a position of strength. If we don’t pay, life will go on. We will continue to get up in the morning, take the children to school and carry out all the outings and activities of social life, regardless of the currency in circulation. The opponents on the other side, however, run a risk. Because they will get nothing if we refuse to pay. So, if they are reasonable, I will be too. But I will not give in. Tsipras did not even try to resist. In Argentina, Kirchner had not given in and yet he was not a Bolshevik! It was then Macri who accepted to have his hand in his pockets. I will not let them steal from us. I will resist, and I will be legitimate in doing so. And the people will understand. Whatever the aggressor and whatever form the aggression takes, it will make mincemeat of them.

So you’re not worried?

No.

Faced with the fascist progression we are currently experiencing and the factional temptation within the police and the army, MP Ugo Bernalicis said you were “very aware of the situation”. Are we living at a turning point?

“This battle between “them” and “us” is not new: the communists and the Nazis were also snatching each other’s votes and workers’ leadership.”

There is a battle. The most dynamic will prevail. But if we are at this point, it is because the old left has disintegrated in mid-flight. Reformism lasted until Lionel Jospin, then it was over. The SP has ceased to take on board social conflict. I remember it well, because I was there. They sold us a Clinton-style centrist strategy. Then the social democrats repeated everywhere that they wanted to “build a dam” against the extreme right, but that was never a political line! It lasted barely half an election, and today nobody believes in it any more. Everyone laughs at the beaver conventions. The social democrats have done nothing with the majority they gained, for a while, in Europe: they have done free and undistorted competition! They applauded the treaties with both hands. Our camp no longer had a head: how can we be surprised today that others occupy the place since the left gave up the fight? This battle between “them” and “us” is not new: the communists and the Nazis were also snatching each other’s votes and the workers’ leadership. Everywhere the left has collapsed. But in France, the refuseniks have raised our own camp. Now we have our backs against the wall all over Europe. Yes, there is a turning point. It is now when everything is at stake.

NOTES

1. “The Revolution is frozen; all principles are weakened; only red caps worn out by the plot remain. The exercise of terror has wearied crime, as strong liquors weary the palate”, we read in Saint-Just’s notes, in 1794, after the execution of the “exaggerated” (Hebertists) and “indulgent” (Dantonists) revolutionaries.

2.Observation and description of phenomena and their modes of occurrence, considered independently of any value judgement.

Trotsky distinguishes three aspects of the “permanent revolution”: the first (opposed to etapism) is the permanence of the revolutionary process or the “transcreation” of the democratic revolution into socialist revolution, for the so-called “backward” countries. The second (as opposed to bureaucratic statism) is the permanence of the socialist revolution itself. The third (as opposed to socialism in a single country) refers to the necessary extension (on pain of degeneration) of the revolution on an international scale because of the global character of the economy.

4.The West Indian writer Édouard Glissant defined it as follows, in 2005: “Creoleisation is a mixture of arts, or languages, which produces the unexpected. It is a way of continually transforming oneself without losing oneself. It is a space where dispersion makes union possible, where cultural clashes, disharmony, disorder, interference become creative. It is the creation of an open and inextricable culture, which shakes the standardisation by the mainstream media and art centres”.