In an open letter published in Harper’s Magazine, 152 writers, including JK Rowling and Margaret Atwood, claim that a climate of “censoriousness” is pervading liberal culture, the latest contribution to an ongoing debate about freedom of speech online.

As we grapple with this issue in a society where social media allows us all to share extreme views, the Victorian writers offer a precedent for thinking differently about language and how we use it to get our point across. How limits of acceptability and literary censorship, for the Victorians, inspired creative ways of writing that foregrounded sensitivity and demanded thoughtfulness.

Not causing offence

There are very few cases of books being banned in the Victorian era. But books were censored or refused because of moral prudishness, and publishers often objected to attacks on the upper classes – their book-buying audience. Writer and poet Thomas Hardy’s first novel, The Poor Man and the Lady, was never published because the publisher Alexander Macmillan felt that his portrayal of the upper classes was “wholly dark – not a ray of light visible to relieve the darkness”.

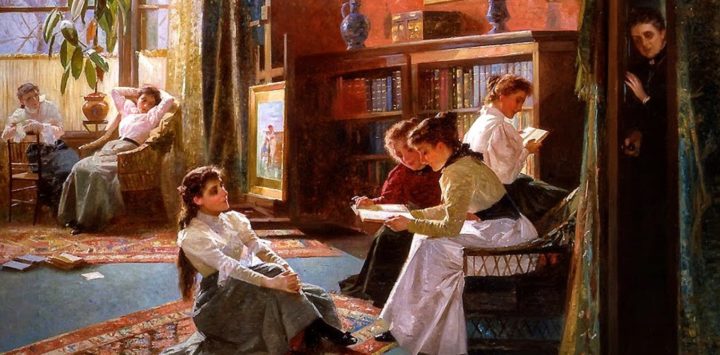

However, more common than publishers turning down books was the refusal of circulating libraries to distribute them. These institutions were an integral part of literary consumerism during the Victorian period as the main means of distributing books.

Most influential of these was Charles Mudie’s Select Library, established in 1842. Mudie’s library was select because he would only circulate books that were suitable for middle-class parents to read aloud to their daughters without causing embarrassment.

This shaped how publishers commissioned and what writers could get away with. Victorian literary censorship, while limiting, managed to inspire writers to develop more creative and progressive ways to get their points across.

Censorship as productive

George Eliot’s publisher, John Blackwood, criticised her work for showing people as they really were rather than giving an idealistic picture. He was particularly uncomfortable when Eliot focused on the difficulties of working-class life.

In Mr Gilfil’s Love Story(1857), Eliot’s description of the orphan girl, Caterina, being subjected to “soap-and-water” raised Blackwood’s censorious hackles:

I do not recollect of any passage that moved my critical censorship unless it might be the allusion to dirt in common with your heroine.

As well as dirt, alcohol consumption was also seen as an unwanted reminder of working class problems. Again in Mr Gifil’s Love Story, Eliot describes how the eponymous clergyman enjoys “an occasional sip of gin-and-water”.

However, knowing Blackwood’s views and anticipating she may cause offence galvanised Eliot to state her case directly to the reader within the text itself. She qualifies her unromantic depiction of Mr Gilfil with an address to her “lady” readers:

Here I am aware that I have run the risk of alienating all my refined lady readers, and utterly annihilating any curiosity they may have felt to know the details of Mr Gilfil’s love-story … let me assure you that Mr Gilfil’s potations of gin-and-water were quite moderate. His nose was not rubicund; on the contrary, his white hair hung around a pale and venerable face. He drank it chiefly, I believe, because it was cheap; and here I find myself alighting on another of the Vicar’s weaknesses, which, if I cared to paint a flattering portrait rather than a faithful one, I might have chosen to suppress.

Here, literary censorship enriches Eliot’s writing. Eliot’s refusal to suppress her work becomes part of the story and reinforces her agenda to portray Mr Gilfil as he really is, a vicar who mixes gin with water because he is poor.

Power in not telling

As well as inspiring narrative additions, censorship was also powerful because of what was left out of a text.

One of Hardy’s most loved books, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, highlights the crimes of sexual harassment in the workplace and of rape. Because Hardy had to be careful about the way that he presented the sexual abuse of Tess, his descriptions were very subtle. This is how he portrays the scene where Tess is sexually assaulted by her employer, Alec D’Urberville:

The obscurity was now so great that he could see absolutely nothing but a pale nebulousness at his feet, which represented the white muslin figure he had left upon the dead leaves. Everything else was blackness alike. D’Urberville stooped; and heard a gentle regular breathing. He knelt, and bent lower, till her breath warmed his face, and in a moment his cheek was in contact with hers. She was sleeping soundly, and upon her eyelashes there lingered tears.

The influence of censorship meant that Hardy could not describe this scene in graphic detail. Instead, his depiction is more sensitive and thoughtful. Hardy does not dehumanise Tess by depicting her as a sexual object to entertain the reader.

By focusing on Tess’s “gentle regular breathing” and the poignant image of her tear-stained eyelashes, Hardy avoids gratuitous depictions of violence while at the same time making us painfully aware of the injustice she has suffered. This makes his portrayal of Tess more powerful and poignant. It can be argued that this was achieved because of the limits placed on his writing, not in spite of them.

In these instances, we can see how literary censorship influenced writers to tread more carefully upon difficult territory. It made them think about whether including violence or socially controversial depictions were necessary or gratuitous to their narratives.

For Hardy and Eliot, censorship and its limits inspired creativity, sensitivity and thoughtfulness. These examples can provide food for thought in the debate today about free speech and censorship. As Hardy and Eliot wrestled with as they wrote, can things be said differently and, in some cases, do they need to be said at all?