Faced with the evidence of the climate crisis, deniers no longer deny the rise of global temperatures, but rather contest its anthropogenic origin, in order to continue with business as usual. As Naomi Klein explained, the “Lords of oil” know very well that the rise in CO2 is leading us to catastrophe, but they have also understood that the transition to a new energy regime is not just a technical fact: it involves the passage from a centralized system, where power and wealth are concentrated in a few hands, to a decentralized system in which power and resources can be distributed. They do not want to lose their privileges, at the cost of sending humanity into misery; they are certain that they will always be able to save themselves. Climate change denial should therefore not be confused with ignorance of the causes of the crisis, which perhaps involves most of the world’s population, starting from those who are already experiencing the crisis firsthand.

But in the “interventionist” field the differences immediately emerge. On the one hand, green washing: passing off the measures put in place well before Greta Thunberg’s protests and the alarm of the IPCC as a commitment against climate change. That’s exactly what the current Italian government does, confirming the old National Electric Strategy issued in 2013, or the mayor of Milan, who passes the Urban Development Plan worked out a decade ago when he was member of the Moratti administration for the city’s response to the climate emergency.

On the other hand, those who work for change find themselves under a single umbrella called Green New Deal, financing the energy transition with a major multi-year investment plan. In this field we find different versions, graded basically between two polarities that are “Sustainable Development” and “Ecological Conversion”. Development means growth and sustainable means infinite: something impossible in a finite planet. But the proponents of this approach protest: growth is only quantitative, while development also concerns the “human factor”. True, but for them development without growth is not possible: one is the condition of the other. Growth, however, they say, does not necessarily mean continuing to exploit the resources of the environment and clog it with waste; it is possible to decouple the increase in GDP and the consumption of physical resources.

It is a thesis on which the principal world agencies (OECD, European Commission, Unep, World Bank) have debated for years without finding any empirical evidence, except for a few sectors and limited periods, but it has been refuted by many studies and, definitively, by “Decoupling Debunked”, a report of the European Environmental Bureau on research carried out by 143 organizations in 30 countries. Unlike those who only do green-washing, this line of thought, which in Italy has its main representative in the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (Asvis) chaired by Enrico Giovannini, believes that an ecological change is of course necessary, but does not impose a substantial change in lifestyles (a “litmus test” is: abolishment of private cars, including electric?) and social organization.

The transition will in fact be in the hands of the companies under the stimulus of a strong popular pressure, but especially in view of convenience (profit) to be created with incentives and penalties: that is, entrusting to a “governed market” the task of getting us out of fossil fuels. Jeremy Rifkin’s theses in his essay “The Green New Deal” are part of a similar approach, suggesting a general redistribution of power in the transition from the fossil era to the “Third Industrial Revolution”, but developing a technical and almost deterministic vision of the transition, imposed, in his opinion, by the four pillars of the future structure: the Internet of information, electricity, things and transport.

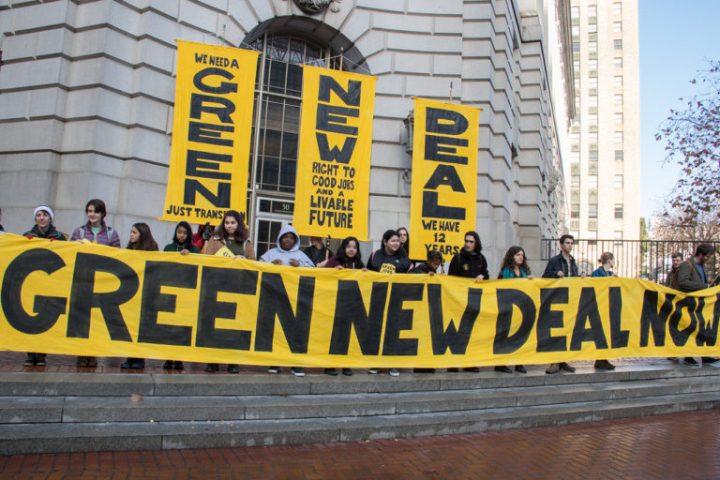

But a Green New Deal is also referred to by figures who claim to be socialists, such as Bernie Sanders and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez in the USA or Jeremy Corbyn and Yanis Varoufakis in Europe, or by movements and activists such as Sunrise and Naomi Klein. The element they have in common, absent in the previous visions, is conflict: for them, the battle against the climate crisis includes objectives and demands of the classes, communities and groups that are exploited, marginalized and more exposed to environmental and social degradation. The members working in institutional processes summarize these objectives in government programs, easily encroaching, as in the case of Diem25, in the perspective of an entrepreneurial state.

Others more linked to the movements try to bring them to light starting from the ongoing conflicts, focusing both on the issues that accompany the spread of right-wing deniers throughout the Western world – phobia and the chase of migrants – and, above all, on the wounds that extraction and development activities inflict on the territories. These are areas in which each community should be able to maintain a relationship with the whole of the living. A relationship in which a central role is played by the quality, distribution and origin of food.

At the heart of this approach the indissoluble link between social justice and environmental justice emerges, the “ecological conversion” that the Italian environmentalist Alex Langer had proposed thirty years ago, specifying that it had to be “socially desirable” to assert itself. This issue is addressed by Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato sì, in which ecological conversion is developed as a reversal of anthropocentric culture – which sees man not as a guardian, but as the master of “Creation” – to promote the reconquest of a sisterhood with Mother Earth, a theme at the center of the recent Amazon Synod. This is the crucial premise of a conflict that allows the poor around the world to assert their rights against the climate crisis of which they are the main victims.

Translation from Italian by Thomas Schmid