The Myth of Innocence: Why Late Birth Was No Grace at All One of the dumbest sayings of the postwar era is the phrase “the grace of late birth,” coined by former Chancellor Helmut Kohl. It suggests that because one was born late, one could not have taken on any guilt during the Nazi era. by Barbara Volhard

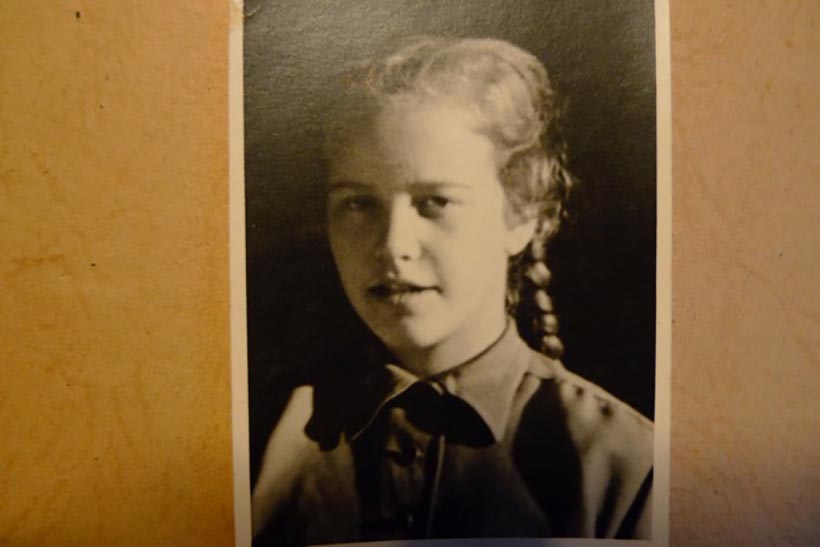

Kohl was born in 1930 and escaped recruitment into the Volkssturm only by luck—boys aged 15 and older were drafted in 1945. Most boys his age were not so lucky. If you’ve seen the film Die Brücke, you get an idea of what that meant (the film is still on YouTube). There are horrific stories of fanatical Hitler Youth members who, as part of the Volkssturm and armed with weapons, mercilessly shot the few prisoners who managed to escape from concentration camps or death marches. One can hardly blame them, because even I — four years younger than Kohl — already had, in 1944 as a ten- year-old, the dubious opportunity to become guilty, and it was more luck than judgment that I did not. To explain that, I need to go back and describe the indoctrination I was exposed to as a child in elementary school, which nearly prevented me from using my own mind.

Background

This also includes where we lived and why. My father was a physician and had held a position as senior physician and private lecturer at the university clinic in Danzig since 1935. When the Nazis occupied Poland in 1939 and took Danzig, he made a positive remark about Jews among friends. One of these “friends” immediately reported him to the Gestapo. The result: he lost his teaching license at the university and was transferred as punishment to the municipal hospital in Bromberg (today Bydgoszcz), where he was repeatedly summoned to the commandant’s office to be berated for not behaving like a “proper German.” For example, he shook hands with Polish patients during rounds just as he did with German patients — something a „respectable“ German was not supposed to do. I learned all this much later, but it explains why my parents were careful not to counteract my school indoctrination. What I Learned in School

So I started school in Bromberg in 1940. In third and fourth grade, we had Mrs. Pich as our teacher, and that’s when things got serious. Until then, my father had explained the world to me; now it was Mrs. Pich who did. We learned not only reading, writing, arithmetic, and local studies, but above all a hierarchy of superior and inferior races, superior and less good Germans, and superior and inferior enemies.

The best race was the Germanic peoples, to which we Germans belonged, as did the English, though unfortunately they were our enemies, but at least they were better enemies. A lesser race were the Romance peoples, including the French, who were “naturally” our enemies. But the Italians were also Romance, yet they were our allies and therefore somehow better. That was confusing, but every rule has its exception, and this must have been one of them.

The worst race was the Slavs — Russians and Poles. They were subhumans. But again, there was an exception: whole regiments of Ukrainians had defected to us and were fighting with us against the Russians, so they were somehow better. And Klara, Adalbert, and Mrs. Poszlednik, who lived in our house, were Poles, but I knew for certain they were not subhumans, so they must have been exceptions too. Human or Animal?

Then there were beings far below even the subhumans: the Jews. Mrs. Pich spoke of them only as beasts, vermin who wanted Germany’s destruction. I imagined them as a mixture of human and animal. Our primer contained a frightening caricature of these beings, and we became afraid of them. But Mrs. Pich reassured us: we didn’t need to be afraid, because the Führer had already exterminated them all. She really said “exterminated,” and that truly reassured me. After all, vermin had to be exterminated, didn’t they?

The Führer as Pop Idol

And the Führer—God had sent him to save Germany. You could tell because he had been wounded in World War I, where he fought bravely, and had gone blind. But God restored his sight so he could save Germany. Mrs. Pich described him as such a wonderful, heroic figure that I — and I suspect my classmates too — idolized him the way children today idolize pop stars. Naturally, I had sworn inner loyalty to “Führer, Volk und Vaterland,” and if someone had asked me to die for him and for the fatherland, I would have gladly done so, just as children in some cultures today are persuaded to sacrifice themselves in bomb attacks.

Children Are Not Taken Seriously

I remind you: I was eight, nine, ten years old when I learned and believed all this. I suspect my parents knew little about the extent of the indoctrination I was exposed to. Our dinner conversations were about other things. The usual parental question, “How was school?” I probably answered with the usual “Oh, same as always.”

When with horror, I heard on the radio on July 20, 1944, about the assassination attempt on Hitler, I said to my mother something like, “Isn’t that terrible,” and I remember her giving a very lukewarm “Yes, yes.” Her reaction didn’t strike me as odd; I assumed it was because, as a child, I was not taken seriously and such things were not discussed with me. So it seemed normal. Just as normal as what Mrs. Pich demanded of us: “If your parents say anything against Hitler, you must tell me, then I will have to talk to them!” Of course, I would have done that, because my parents, I knew, would not have believed me about how great Hitler was. No, Mrs. Pich would have had to “talk to them.” So much for the “grace of late birth.” Even at eight or nine, I could have become guilty. Did other children become “guilty” in similar ways? Could they continue to live with it afterwards?

Homework: Reading the Newspaper

By the way, our homework in third grade already included daily newspaper reading, especially the Wehrmacht report. The next day we were quizzed on it and had to mark the front lines with little flags on the large map hanging in the classroom. So of course we noticed how the Eastern Front was constantly approaching Bromberg. But again, Mrs. Pich reassured us: the Führer was working on a miracle weapon. It was almost finished and so magnificent that it would end the war in one blow. Today we know this “miracle weapon” as the atomic bomb.

Having a Father Became Embarrassing

Less magnificent was the fact that more and more children in my class were losing their fathers, who — according to the death notices — had all died a hero’s death, naturally in the service of Führer, Volk und Vaterland. Not having a father was becoming “normal,” and I was almost embarrassed that my father was not fighting at the front, was therefore not a hero, and was still alive. I was glad about it on one hand, but on the other I answered the increasingly common “tactful” question from adults about my father with a defiant: “He is deployed on the home front.”

“Home” to the Reich

The Eastern Front came closer and closer, and in summer 1944 many men sent their wives and children “home to the Reich” (homeland empire). That was then forbidden as defeatism (“defeatist” was anyone who did not believe in victory), and in the end, when everyone was encircled and flight was finally allowed, there were hardly any escape routes left.

At the same time, my father was transferred from Bromberg to Gotenhafen (today Gdynia), so we had to move there. I was ten, my younger sister seven, my baby sister ten months old. My mother managed to get permission to bring us three children to relatives in the Reich, supposedly only for the duration of the move, so we would be “out of the way.” She had to promise to bring us back immediately afterward. She was only allowed to “drop us off” and had to return on the same bus that brought us to Masserberg in Thuringia.

My grandfather had a vacation house in Masserberg, large because he had ten children. Several of those children’s families—mostly mothers with their children—had fled there from the bombings in Frankfurt and Magdeburg, so 21 people lived in the house, including 13 children aged from a few months to 14 years. In February the next year my parents joined us, and it became even more crowded. But from September 1944 to February 1945, I was there without my parents for half a year.

Lonely Among many Children

I had been very excited about this trip: at last, I would get to know my cousins! And a house full of children — that surely had to be exciting! Of course, I had no idea that this would be a farewell forever, a farewell to my home, to my friends, to the sea I longed for so much, because naturally I believed the fairy tale that we would soon return. And I looked forward to the apartment in Gotenhafen, which lay very close to the sea, as my father described in his letters.

It turned into half a year of deep loneliness. The younger children were too young for me, and for the older ones were too young. I attended a Düsseldorf grammar school that had been evacuated to Masserberg; the spa building had been converted into a boarding school. As an outsider, I found no connection in the class — perhaps also because the children there were no better off than I was: they too had been separated from their parents.

At some point, I began wetting my pants again, something that filled me with almost deadly shame: to wet your pants at ten years old, and every day at that! Of course, I didn’t understand that it was psychological; I was only full of horror and shame. An aunt, to whom I had to confide because I needed fresh underwear every day, reacted very sensibly, and eventually I trusted her enough that I was able to stop the “wetting” after a while. But I know all too well how the many children in the Kinderlandverschickung (evacuation of children) must have felt — sometimes placed with strange foster families, often in institutions where probably hardly anyone helped them, just like the “evacuated” children in that Düsseldorf grammar school.

The New Uncle

In the autumn of 1944 — I think it was October — I knocked one day on that aunt’s door, but didn’t wait for a “come in,” and simply opened it. To my shock, a strange man was lying in her bed! I quickly wanted to close the door again, but he beckoned me over, asked who I was, and then explained: he was my aunt’s husband, my father’s brother, and I must not tell anyone that he was there. I nodded, confused. I knew at least that this brother of my father was a Luftwaffe (air force) pilot; as I left, I saw his uniform hanging over a chair and stood outside the door, stunned.

Because I thought: if I must not tell anyone that this uncle is here, then that means he is not here on leave. And that means he has deserted. And that means he is a traitor to Führer, Volk und Vaterland! A coward! So I must report him!

But then — I knew this very clearly — he would be shot. And I thought that was right: how could we win the war if soldiers ran away? On the other hand, he was my uncle, my aunt’s husband, the father of three cousins. I fell into a terrible conflict between two loyalties that were equally important to me: loyalty to “Führer, Volk und Vaterland,” and loyalty to my family. And I was terribly alone with it, because I could ask no one: in the family they would of course all say that I must not report him, but had I asked the teacher, I would already have betrayed him.

Luck and Reason

I no longer know how long I carried this around — days or weeks. But eventually I reached a point where I could no longer bear it. I knew I had to make a decision, and that I had to think very carefully. I had learned from an earlier, completely nonpolitical but important experience at age seven that if you think carefully (that is, use your mind), you can work your way out of terrible, even life-threatening situations by yourself. I am still grateful to Professor Schmidt, the head of the ENT department at the University of Danzig, who helped me reach that insight.

So I sat down, thought carefully, and came to the following conclusion: if I report my uncle, he will be shot. I cannot undo that. But if I do not report him, I can still change my mind later. So I decided — for the time being! — not to report him, and hoped that some kind of sign would come from somewhere telling me whether I should — or should not — report him. It may sound like a rather sophistic way of avoiding a decision. But this conscious decision relieved me, because I had handed the real decision over to a childishly magical “sign.” After all, I was only ten years old.

The Miracle

And then the miracle happened: the “sign” came! But not until January 1945. In the months before, this uncle had remained nothing but a coward and a traitor to me; I felt only contempt for him. But in January 1945, my youngest sister — who had been only ten months old when we arrived in Masserberg in September 1944 — was now fourteen months old. She could stand, but not yet walk.

One day I opened the door to the common living and dining room and stopped: there sat my uncle, having stood my little sister in front of him, and she staggered toward him, laughing and squealing with joy. He caught her, set her up again, encouraged her to walk again and again, and she was visibly happy. The whole scene had such tenderness that I immediately knew: this was the “sign”! I must not report him! I was infinitely relieved. And at the same time, I saw this uncle for the first time as the loving person he truly was, not as the distorted image I had been taught to see. When the Americans occupied Masserberg in April 1945, he put on his uniform and surrendered. When I saw that, I thought in horror: why is he doing that? Now he will be shot! I had not yet learned that prisoners of war were not always executed. Memory and Late Understanding

I assume that because the story ended well, I was able to forget it. When it came back to me, both my parents and that uncle and aunt were already dead, and I had never told anyone. But now I was about sixty years old, and suddenly I felt hot and cold. Only then did I understand on what razor-thin edge I had been balancing, and how easily I could have slipped to the wrong side. I understood that it was a mixture of luck and reason that had saved me. The luck was that my uncle was a family member. Had he been a stranger, I would have reported him immediately and without hesitation. But that luck forced me to use my mind. And I also knew: had I decided wrongly, I would not only have sent my uncle to his death, but I myself would no longer be alive. I doubt I could have lived with that guilt; I do not believe I could have forgiven myself, even knowing I had been only a child.

At the same time, I wondered how many children of my age cohort must have faced similar decisions, and how many of them later could not live with it — or if they could, how. Perhaps by claiming that dreadful phrase “the grace of late birth” as a kind of absolution?

Terrible Question — and No Answer

I could not. When I visited a concentration camp for the first time in 1969, Ausschwitz, I was shaken. Not only by the horror, which had already shocked and traumatized me in 1945 as an eleven-year-old through the pictures in the occupation newspapers, but also by the realization that I could not answer a terrible question: what would have happened if my schooling had continued uninterrupted? Would I, at eighteen, have become a perfectly capable concentration-camp guard or secretary? I was thirty-five and knew all too well how foolish and thoughtless I had still been at eighteen.

Against this background, I view the prosecution of then eighteen- and nineteen-year- olds with mixed feelings, as well as the supposedly “great” processing of our past. Nothing was processed — on the contrary. Most of those who knew exactly what they were doing returned to office after Hitler or were able to flee with state or church help. Those who were convicted were often the ones too young or too foolish to truly understand what they were doing, and who had likely just followed orders thoughtlessly. That cannot be said of the Globkes, Kiesingers, and Filbingers, to name only a few. (Anyone who wants to know more should read Ralph Giordano’s The Second Guilt.)

Helplessness

Above all, we late-born and younger ones were left alone with this so-called “processing.” It began with our history lessons, which were at least partly still taught by Nazi teachers who successfully avoided teaching us the history of 1933–1945, let alone how it came about. My own history lessons (graduation in 1953) ended in 1914. Later I heard from younger people that this was still the case in the early 1960s. When I spoke in the 1990s with an acquaintance about the story of my uncle — he was about ten years younger than I — he told me that a third (!) of his classmates had killed themselves because they could no longer live with their Nazi fathers. These suicides are a terrible expression of the helplessness to which we younger ones were abandoned. For these boys, their late birth had become a deadly curse. Even in my teacher training for German and English in the 1970s, there was never any talk of history or coming to terms with the past, let alone how we should teach it to our students. So I was helpless when confronted with remarks like: “My grandma says it was all completely different.” What could I say against a grandmother who could not bear that her husband had died for a criminal regime?

Germans of Different Value

The “grace of late birth” is therefore a fiction. But there was a “grace of early birth,” which hardly anyone knows about, and which must therefore be told. For that, I must return once more to Mrs. Pich.

In Mrs. Pich’s mental universe, even Germans had different values. Highest were the Reich Germans — those who had moved into the part of Poland now called “West Prussia” after the occupation. My family belonged to them, and I was proud not only to be Germanic, but also Reich German.

Then there were the Volksdeutsche, who had a lower “value.” These were ethnic Germans who had already lived in Bromberg when it was still Polish (many of whom would immigrate to West Germany decades later as ethnic German repatriates). Mrs. Pich taught us this hierarchy, but within our class we made no distinction between Reich Germans and Volksdeutsche.

The third-best Germans were the “Germanized.” These were Poles or other foreigners who, according to Mrs. Pich, found Germany so wonderful that they wanted to become German and were therefore “Germanized.” We were to get to know such “Germanized” children and also learn that Mrs. Pich clearly held nothing of them.

“Germanized”

Our classroom had the oldfashioned school benches that may no longer exist today: each bench screwed to a table for two pupils. These benches stood in three rows of six or seven benches each. We sat distributed across these three rows when one day (I think in fourth grade, when we were nine years old) Mrs. Pich ordered us to squeeze into two rows so that the third row would be free. We didn’t like that at all; we had to rearrange ourselves completely.

Then the door opened, and 12–14 children our age entered and sat in the freed row. Among them was a girl so beautiful, with her whiteblond hair, that I immediately thought: I want her as a friend! But nothing came of it. Because now Mrs. Pich explained that these children were Germanized Poles. Our task was to watch them and make sure they did not speak Polish. She also assigned each of us better pupils one of these children. During the short breaks we had to check their homework for the next lesson and mark mistakes in pencil. Mrs. Pich then checked our corrections.

Secret Resistance of NineYear Olds

This was the first time I felt something like a spirit of resistance. What was this supposed to be? These children were now Germans — so everything should have been fine. Were we supposed to snitch? That was impossible. I suspect the others in the class felt the same, though we never talked about it. The boy assigned to me was so shy he hardly dared speak. I tried to explain his mistakes as kindly as possible, but he only nodded. And these short breaks, now filled with extra work, were no longer breaks at all, but a burden.

The only real break we had was the long recess. During it, we German children ran out onto the schoolyard — and, as if we had agreed on it, as far away from the building as possible, where we played. Occasionally I watched from afar as our Polish classmates stood in three small groups along the wall of the school building, talking angrily (you could see it in their faces). None of us wanted to know whether they were speaking Polish or German. Snitching was out of the question. But I also didn’t know why these children were so angry.

I no longer remember how many weeks or months this situation lasted. But one day the Polish children were gone. Simply gone. Mrs. Pich did not consider it necessary to explain anything — and we did not ask. I think we were simply relieved; at least I was. Since we had never talked about it among ourselves and did not talk about it now, I can only assume that we all felt the same. Above all, it had been a burden — one we did not understand, but nevertheless felt. For years I wondered what had become of those children.

Grace or Curse?

Only decades later (and this too is part of our supposedly “great” processing of the past) did I learn about the “Lebensborn” program — that dreadful institution that took “Aryan- looking” Polish children from their parents by the thousands, sometimes snatching them off the street or from kindergarten, to Germanize them and have them adopted by SS or SA families.

Here one can speak of a “grace of early birth.” I at least hoped that my Polish classmates, who were already nine years old at the time, had a chance of finding their real parents again, because they could still remember them and their real names. It was different for the older man I met a few years ago at an exhibition about the “Lebensborn” program in Freiburg. He had been taken from his Polish parents at the age of two and had spent his life searching in vain for his real parents. For him and many others, the late birth had not been a grace but a curse.

Conclusion

I felt it necessary to tell this story because today, in 2025, the media cannot get enough of pointing out the “malice” of the Russians, among other things with the argument that they abduct Ukrainian children to “Russify” them. That they may have learned such things from us Germans is never mentioned, though it belongs to the story. But more than that: from my own school days I know quite well what Ukrainian and Russian, Israeli and Palestinian, Sudanese and Myanmar children — indeed all children who grow up in war — learn in school: “We are the good ones, the others are the bad ones and must be annihilated.” Annihilated! As a child, you think that is normal. That is why there are child soldiers worldwide, who also consider their soldiering normal, even sacrificing themselves in bomb attacks because they truly believe they are doing something good for their community.

Distinction and Exclusion

What we Germans should have learned from our history — but what very few of us truly learned — is the difference between distinction and exclusion. Exclusion from restaurants, trams, theaters, schools, universities, professions, etc., was how the exclusion of the Jews began, which ultimately ended in their exclusion from life itself. This terrible consequence is always inherent in “exclusion,” even if one believes one does not mean it that way.

When people are “different” from us — have a different opinion, look different, speak differently, think differently, have a different religion or culture — understandably, this may initially repel us. Caution toward the unknown is innate and has a protective function.

But equally innate is our curiosity about everything “other,” which we share with many animals. It can help us discover that such “others” may be interesting and enriching. For that reason alone, we must never exclude them, but should look and listen closely. We may and should, however, distinguish ourselves from what seems wrong or uncomfortable to us. But that is far more demanding than simply putting people into boxes! Because it requires speaking with the “others,” perhaps even understanding them. That requires thinking and acting, even finding arguments — something many of us find too burdensome.

One thing, however, is certain: enduring the “others” beside us and among us is guaranteed to be easier than enduring terror or bombs. If humanity is to survive, we must manage this. And I believe we can.

There is a wonderful three-minute Danish film on YouTube from seven years ago, in English but with German subtitles, that can help us: “What happens when we stop putting people into boxes?” The film shows us that — however different we may seem — we have far more in common with one another than we think.