(In Kazakh culture, the yurt is the traditional nomadic dwelling: a portable circular structure symbolizing home, hospitality, and community.)

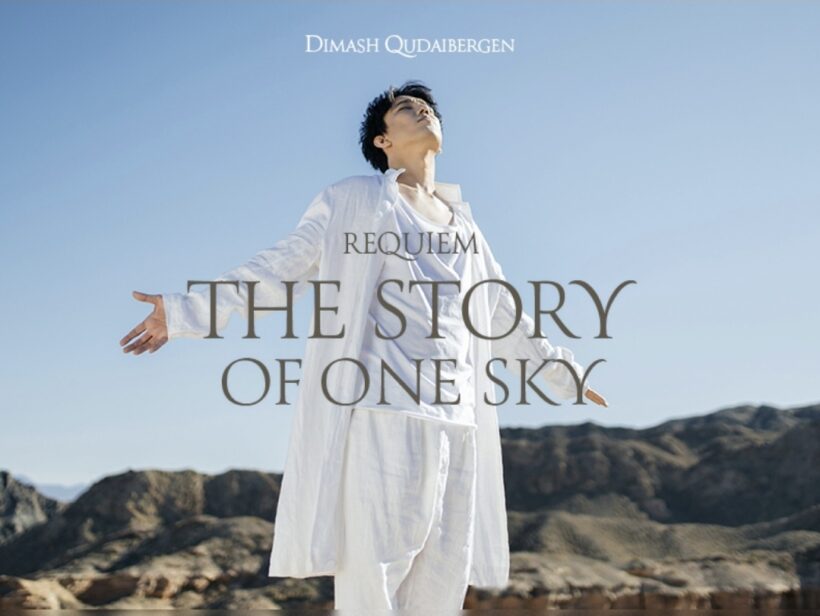

“Music alone cannot change the world, but it can change people, and people can change the world.” —Dimash Qudaibergen

We live in an age that has turned art into background noise. Platforms and algorithms dictate the tempos of listening; spectacle is measured in clicks, not in memory. Art is confused with entertainment, and entertainment with distraction: everything is fast, everything is disposable. In this landscape, the voice that halts the listener is no longer the loudest, but the most extraordinary in its sublime rarity: one capable of cutting through the thickness of saturation to say something true.

Music, once invocation, ritual, and resistance, has become trapped between the showcases of the industry and the banality of fashion. Where song should name the unnameable and build bridges between opposing shores, we find recycled formulas, standardized aesthetics, and rhetoric that speaks of love while sounding hollow. The word universal has been used so many times it has lost its meaning; the promise of cultural unity has been reduced to a market label, while mediocrity erects itself as the dominant standard.

In this worn context, the emergence of an artist capable of overflowing the boundaries of genre, language, and geography is not merely an aesthetic event: it is an ethical challenge. When that artist does not simply occupy a place on the stage but turns it into common ground for audiences who might never have shared the same hall, we witness more than a concert: we witness a political act in the highest sense of the term.

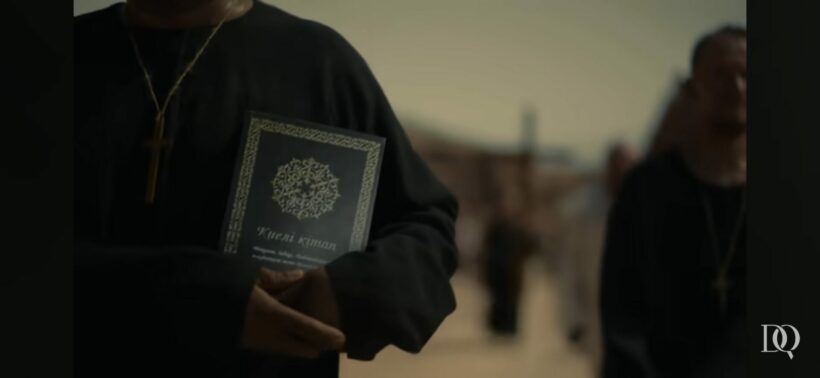

This “political act” is not inscribed in party rhetoric or ideological agendas. It manifests instead in the ability of his art to place divisions in parentheses and neutralize antagonisms. In a concert hall where audiences from all continents gather—from ancestral routes to rival metropolises—geopolitical tensions and cultural prejudices become irrelevant for the duration of a song. His voice, which navigates between languages and traditions, becomes neutral territory, an unofficial diplomacy that operates on the plane of the senses. In this space, true power lies not in imposing a message but in creating the possibility for disparate people to recognize themselves in a shared emotion, and in that shared vulnerability, to lay the foundations for future coexistence. It is an act of resistance against the dispersal and isolation inherent to the digital and political age.

This kind of art is not born from mere marketing calculation or submission to the algorithm. It is nourished by a decision: to inhabit music with the utmost excellence and beauty, and as a space of poetic opposition to the division that prevails in technological and political times. Here, every note, every gesture, and every silence is oriented toward a greater purpose: to reconnect human beings with themselves and with one another. This intimate and collective encounter is not a mere aesthetic refuge but the beginning of a deeper quest. It is a conscious act of elevating sensory experience into ethical reflection. To pursue the beauty of thought in order to understand virtue. And although few may recognize it immediately, when such art appears, something shifts in the order of the collective. The audience’s breathing synchronizes, differences fall silent, and for an instant—brief, yet enough—the possibility of a different community comes into view. In that instant lies the reason why we still need art: not to distract us from reality, but to remind us that it is still possible to transform it.

Historical and Cultural Context

“I never forget that I represent not only myself, but an entire country, its history, and its culture.” —Dimash Qudaibergen

In the vast plains of Central Asia, where the horizon seems endless and the wind carries echoes of ancient caravans, in the sacred steppes where man tamed the horse and apples were born, Dimash Qudaibergen came into the world. His origins in Kazakhstan are no incidental biographical detail: they are the deep root of an art that breathes in two tempos—the millennia-old tradition and global modernity. Kazakh culture, nourished by centuries of oral poetry, epic songs, and nomadic melodies, is inscribed in his voice as a living archive. Each note carries the memory of a geography that has been a crossroads of routes, empires, and civilizations, and that has learned to survive through oral transmission and cultural intermixing.

In Kazakhstan, music is neither a luxury nor an accessory, but an essential fabric of collective identity. From the kuis performed with the dombra—the classic and symbolic Kazakh string instrument, often played in rhythms that gently resemble the gallop of horses—to improvisational songs recounting feats and tragedies, the Kazakh sonic tradition is marked by an intimate relationship between landscape, history, and emotion. Dimash grew up immersed in that tradition, where music is both historical narrative and spiritual vehicle. Being born into an environment where song, values, and respect for traditions still retain ceremonial and communal functions gave him an understanding of art as a social and transcendent act, very different from what predominates in the global industry.

His education was not limited to absorbing that heritage. From an early age, he moved naturally—both instinctively and academically—from folk music to classical music, from academic singing to the exploration of popular genres. Educated in conservatories and guided by teachers who recognized his exceptional potential, he integrated bel canto techniques, advanced breath control, and a repertoire ranging from opera arias to contemporary ballads. This hybrid training allowed him not only to achieve a rare vocal range but also to understand that each style is a language, and that true art consists in being multilingual and multi-sign without losing one’s own voice.

Today, Dimash sings with his soul and performs in at least fourteen languages: Kazakh, Russian, English, French, Italian, German, Bulgarian, Romanian, Ukrainian, Turkish, Arabic, Mandarin, Japanese, and, more recently, Spanish. He incorporated the latter with a self-composed piece, highly lyrical and dramatic—an artistic and cultural gesture marking a new bridge with the Spanish-speaking world. Later, he would also perform a piece alongside Plácido Domingo and José Carreras, occupying the place that in the original Three Tenors format belonged to his greatest musical idol, Luciano Pavarotti. This encounter took place in the context of the international Virtuosos competition, which seeks and promotes the finest young talents in music worldwide. Days from another planet for the hegemonic Western West of the world, to put it redundantly. Soon, he will debut his first concerts in Spain and Mexico, thus consolidating an unprecedented connection between Central Asia and the Latin sphere. It is worth noting that he sold out in a matter of minutes—to the astonishment, this time, of the Eastern side of the Earth.

The 21st century found him in a hyperconnected yet culturally fragmented world, where music circulates at the speed of a click, yet audiences isolate themselves in bubbles of preferences and algorithms. Dimash bursts into this scene not as a product designed for a niche, but as an unexpected bridge: in every language he interprets, he not only pronounces the words but takes ownership of their emotional cadence, opening cracks in the borders of taste and identity.

His media trajectory defies dominant logics. He rose to international fame through a highly demanding television competition in China (after winning all the competitions in the Slavic world), a space that, far from pigeonholing him, allowed him to display his versatility and connect with a massive audience without yielding to cultural homogenization. Since then, he has chosen stages and collaborations that expand his reach without diluting his authenticity. Instead of adapting to a preexisting Western mold, he has forced that mold to expand to include him, introducing audiences worldwide to the musical richness of Central Asia while also embracing universal repertoires.

For all these reasons, Dimash is not merely a performer who moves between genres: he is a node of cultural intersection. His work connects the steppes, mountains, and forests of Kazakhstan with European opera houses; traditional melodies with contemporary harmonies; the intimacy of chamber singing with the spectacle of pop music or the power of the dombra. In him, the local and the global do not stand in opposition: they intertwine, reminding us that identity is not a border but a space of transit, a crossing zone. And it is precisely in that space where his voice—literally and symbolically—finds its greatest power. Because it has Power.

Reception and Impact: The West Faces Dimash

On the global stage, Dimash’s emergence has generated varied reactions. For Asian and Eastern European audiences, accustomed to high standards of excellence, his presence represents a natural continuation of vocal traditions that still value technique as a cultural heritage. However, in much of the West—where the music market has become dependent on industrial production patterns and digital metrics—his art is perceived as a phenomenon “outside the catalog.” This gap does not stem from a lack of quality, but from a clash of paradigms: a world that has reduced music to a reproducible product is confronted with a performer whose essence cannot be encapsulated in short formats or recommendation algorithms.

The initial contact of the cultivated Western public with Dimash is often mediated by technical astonishment. The more than six octaves—which, incidentally and paradoxically, matter far less to him than the idea that love in performance is what truly counts, to paraphrase his own statements—the seamless register changes, the vocal and physical theatricality, act as an immediate entry point. Yet if listening remains on that surface, the core of his proposal is lost: the ability to provoke an integral aesthetic experience that transcends technical admiration to become an emotional and often spiritual event. The magnitude of that experience challenges fragmented consumption habits, demanding time, attention, and openness.

Cultural biases play a central role in this reception. In the West, popular and classical music have historically been segmented into separate circuits, with audiences that rarely intersect. Dimash breaks this separation not through superficial fusion, but as a simultaneous inhabitant of both worlds. To understand him, the Western listener must “unlearn” certain habits: stop classifying him as a tenor, pop singer, or viral phenomenon, and begin to listen to him as a complete performer whose repertoire does not conform to a single category.

This process of unlearning is not simple. It requires renouncing the logic of playlists and predefined genres, and accepting that a song can be a dramatic journey, that a ballad can contain an ethical statement, that an aria can converse with pop without losing dignity. In this sense, Dimash challenges the Western notion of specialization: he does not seek to be the best in a niche, but to open a space where the borders between genres and traditions become irrelevant.

The deep, active, and conscious listening that Dimash demands is an antidote to musical superficiality. In a time when songs are skipped before a minute and a half, his work obliges the listener to inhabit every measure, to accept silence as part of the message—masterfully so in his Ave Maria—and to understand that music can be an act of total presence. This breaking of habit may be the greatest impact he can have in the West: not only changing musical taste, but giving back to the listener the capacity to truly listen.

Iconic Collaborations and Stage Excellence

His career has been nourished by collaborations that are, in themselves, cultural dialogues. With Igor Krutoy, he has built bespoke pieces created for his exceptional range and timbre. Krutoy has described him as “a unique voice that internalizes music with incredible talent,” and has designed for him productions that are authentic total works of art.

With Lara Fabian, in Adagio, he achieved a fusion of timbres that she herself described as “extraterrestrial” for its power and purity. This meeting not only sealed a memorable vocal communion but reaffirmed his ability to merge voices from different origins without losing identity.

In Moscow, in productions such as Rhapsody on Ice, Dimash has sung accompanied by a symphony orchestra, choirs, electronic elements, and monumental staging, while elite skaters performed choreographies on ice. The technical and creative excellence of these performances—where musicians, artists, technicians, and lighting achieve a rare degree of mastery—has turned them into cult icons.

Humility and Legacy

Yet what most moves those who know him is his humility. Amid the grandeur of his concerts and global recognition, Dimash maintains a close manner, a human quality that inspires. He is, as many agree, a luminous being. And in an era marked by worn-out words and hollow promises, his presence transcends music.

Dimash embodies an unwritten architecture of peace. His concerts are tacit agreements in which there are no winners or losers, but a space where identities coexist. This agreement bears neither ink nor signatures: it is sung, heard, and offered to the other. In a time when beauty can be, at once, an act of truth and a commitment to life, his music reminds us that we still have a common language. Far from being a hiding place or an aesthetic privilege, the music Dimash offers is a declaration that, as long as we can be moved together, there is hope for building something different.

Ethical Call and Legacy Projection

If Dimash has proven anything, it is that music, in the hands of a conscious performer, can serve as a real bridge between worlds in conflict. It requires neither simultaneous translation nor diplomatic agreements: precise intonation, phrasing charged with intent, and the contained gesture at the exact moment are universal languages that speak directly to the human core. In times of global crisis, this ability is more than an artistic merit: it is a political resource in the noblest sense of the term.

The projection of his legacy goes beyond sales or streaming figures. It is likely that, fifty years from now, his work will be studied not only in music academies, but in faculties of sociology of art, postcolonial studies, and cultural diplomacy. His figure could become a paradigmatic case of how an artist from the global periphery, without renouncing technical excellence or the authenticity of his culture of origin, can intervene in the global conversation on identity, coexistence, and memory. His work condenses the challenge of 21st-century globalization: to be universal without losing one’s roots, to connect without homogenizing, and to use technology to build bridges instead of bubbles.

In this sense, his legacy will not be solely that of a virtuoso, but that of a cultural mediator. Just as Caruso, Callas, or Pavarotti were technical and expressive references of their time, Dimash may be remembered as the performer who, in the digital and polarized era, restored to art its dimension as a communal event. He will be cited not only for his voice, but for having used that voice to build a space of encounter.

Dimash’s work functions as a tacit agreement between performer and audience: here there are no winners or losers, no identity imposed over another, but rather a proposed experience in which diversity is heard and resonates. This pact is neither drafted nor inscribed on paper; it is celebrated in song, in listening, in encounter. And in that act, art fulfills one of its oldest and most essential functions: reminding us that, despite fractures, we still have a common language.

In an environment overflowing with forgettable speeches and ceremonial noise, Dimash’s music acts as a reminder that beauty can be, at the same time, an act of truth and a commitment to life. It does not arise to flee from the world nor as a superfluous ornament: it is a call to urgent, shared existential commitment. As long as we can be moved together, there is still hope to build something different. This is the architecture of peace he leaves us: an open score, written in all languages, for each generation to interpret in its own way, but always with the same essential purpose.

“If there is one thing I want to leave to the world, it is the certainty that music can be a place where no one has to take up arms.” —Dimash Qudaibergen, 21st century