Researchers have made a direct link between climate change and the increasing frequency and intensity of wildfires around the world, while also linking it to thousands more smoke-related deaths over the last several decades.

In two separate papers, research teams from Dalhousie University, Belgium, the UK and Japan studied the extent of wildfires and their effect on human health, finding worsening outcomes for both. In fact, the team estimates that there were fewer than 669 wildfire smoke-related deaths annually in the 1960s, but that that rose to 12,566 a year in the 2010s.

One study, published in Nature Climate Change, compared wildfire models with and without the effects of climate change, showing an increase in the occurrence and strength of wildfires in many regions, especially in sensitive ecosystems in African savannas, Australia and Siberia.

The findings, however, point to large regional differences.

In Africa, where up to 70 per cent of the global burnt area is located, there was a marked decline in wildfires, due largely to the increase in human activity and land fragmentation that makes it harder for fires to spread.

Conversely, in forested areas such as California and Siberia, the number of fires is increasing, due to longer periods of drought and higher temperatures linked to climate change.

The study is important because it shows and quantifies the influence of climate change on increasing wildfires worldwide, especially given the impacts of wildfire on society and its feedback to climate change,” says Dr. Sian Kou-Giesbrecht, an associate professor in Dalhousie’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences who conducted and analyzed the simulations of the Canadian fire model and co-authored both reports.

Loss of control

The team used models that considered various factors such as climate, vegetation and population density. The researchers stress that while human activities such as fire suppression and landscape management can have a dampening effect, this is often not enough to fully counteract the impact of climate change, especially in years with extreme weather.

What is striking is that in periods with low to moderate numbers of fires, direct human interventions have a large effect. However, in periods with many fires, the effect of climate change dominates, meaning that in these cases we lose control, said Seppe Lampe, a climate scientist at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel and one of the lead authors of the study.

Although human activities such as landscape changes and population growth generally reduce the area burned, the effect of climate change continues to grow.

The simulations show climate change increased global burned area by almost 16 per cent for 2003 to 2019, and increased the probability of experiencing months with above-average global burned area by 22 per cent. Moreover, the contribution of climate change to burned area increased by 0.22 per cent per year globally, with the largest increase in Central Australia.

Our results highlight the importance of immediate, drastic and sustained greenhouse gas emission reductions along with landscape and fire management strategies to stabilise fire impacts on lives, livelihoods and ecosystems, the paper states.

Deaths from wildfire smoke rise

A separate paper found that climate change may have increased the proportion of wildfire smoke-related deaths tenfold over roughly five decades, a phenomenon that had been largely unquantified.

Researchers, including those from the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Japan, used fire-vegetation models in combination with a chemical transport model and health risk assessment framework to attribute global human mortality from fire fine particulate matter emissions to climate change between 1960 and 2019.

They found that between one and three per cent of fire deaths in the 1960s were attributable to climate change, while up to 28 per cent were in the 2010s depending on the model used.

South America, Australia, Europe and the boreal forests of Asia had the highest levels of mortality.

“It can be tricky to attribute wildfire to climate change because of the complexities of the interactions between fire weather, global change effects on potential fuel, land management and ignitions, but in these international projects we have made a robust attribution of wildfires to climate change using multiple models. We also put this into context by quantifying the human mortality associated with intensifying wildfire smoke,” says Dr. Kou-Giesbrecht, adding that if the current pace of climate change continues, the area of burnt land and associated health impacts will increase significantly in the coming decades.

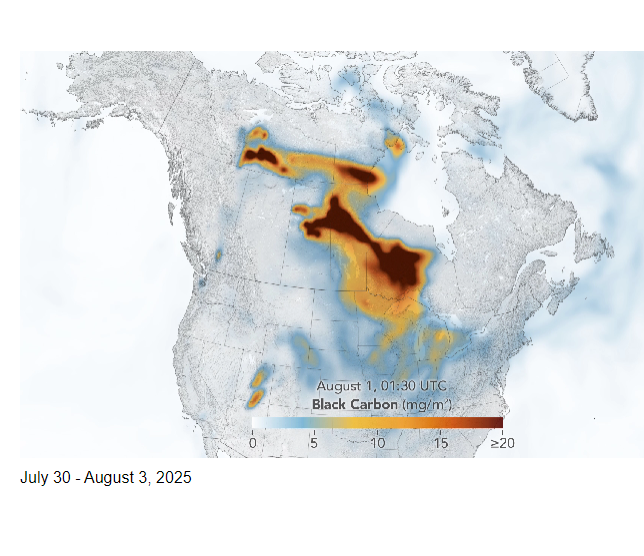

(NASA Earth Observatory video by Lauren Dauphin, using GEOS-5 data from the Global Modeling and Assimilation Office at NASA GSFC.)

NASA Report

Story by Lindsey Doermann

Smoke from hundreds of wildland fires burning in Canada created hazy skies and poor air quality across multiple provinces and northern U.S. states in late July and early August 2025. Air pollution affected areas of the Northwest Territories, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario, according to news reports, as well as parts of the U.S. Upper Midwest and Northeast.

The animation above depicts the concentration and movement of wildfire smoke from July 30 to August 3, 2025. It shows black carbon particles—commonly called soot—from Canadian fires drifting across North American skies during that period. Black carbon is a component of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) air pollution, which can aggravate cardiovascular and respiratory conditions and create other health issues.

The black carbon data come from NASA’s GEOS forward processing (GEOS-FP) model, which assimilates data from satellites, aircraft, and ground-based observing systems. In addition to satellite observations of aerosols and fires, GEOS-FP also incorporates meteorological data such as air temperature, moisture, and winds to project the plume’s behavior.

The animation shows how smoke plumes in northern Canada spread and drifted to the east. On August 2 and 3, parts of multiple provinces were under air quality warnings. These are issued when Canada’s Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) reaches level 10 or above, indicating a very high health risk. Visibility was reduced to 200 meters (660 feet) in Fort McMurray, Alberta, on August 3.

Poor air quality also affected areas farther from the fires as a high-pressure system pushed smoke from higher in the atmosphere back toward the surface, meteorologists said. For instance, authorities in Minnesota issued an air quality alert for the entire state for nearly a week. People in several Northeastern states were advised to limit outdoor activity because of the smoke on August 3, according to news reports, and the AQHI in Toronto, Ontario, reached level 7 that day, denoting high health risk.

Canada is facing one of its worst fire seasons on record in terms of area burned. As of August 3, more than 6.6 million hectares (16.3 million acres) had burned, according to the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Center. That exceeds the 25-year average of about 2.2 million hectares but trails the more than 12.3 million hectares burned by this date in 2023, a record-setting year. On August 3, 2025, 159 and 81 fires were burning in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, respectively, many of which were classified as out of control. Another 106 were active in the Northwest Territories.

For at least the second time this season, smoke from these blazes traveled across the Atlantic Ocean bound for Europe. Carried by a strong jet stream, it was expected to reach Western European skies between August 5 and 7. In mid-June 2025, another smoke plume from Canada degraded air quality and reddened skies in Central and Southern Europe.

__________________________________________________

Source: Research reveals global increase in wildfires due to climate change despite human interventions, Dalhousie University