In the context of the ongoing humanitarian crisis surrounding refugee populations Samos is the Aegean island that people often forget. It exists in the shadow of Lesvos, people are familiar with the name Moria and the images it evokes. Yet until very recently the Vathy Reception Centre on Samos has been under discussed and under reported. Yet over the past 6 months the refugee population on the island has grown and over the final months of 2018 and the first few weeks of January 2019 has fluctuated between 4000 and 5000 people. The Reception Centre has an official capacity below 700 and as a result the majority of people now live outside of the centres fences within an area referred to as ‘the jungle’.

Before this increase in numbers, when you first arrived on the island you were met by Frontex, your identity established, you were registered and then you were found a space within the Reception Centre, either within a container or a tent was provided. Now, due to over population and crowding the registration process remains the same but you are sent out into ‘the jungle’ to find a place to sleep and to purchase a tent from one of the stores in the small town of Vathy. As a result many people, including families with young children and unaccompanied minors, live in make shift spaces relying on wooden pallets, stones and tarpaulin to build themselves a shelter from the extreme storms that also plague the island in the winter. Food is provided by the Reception centre, although the queue to receive each of the three meals a day you have access to is, at current estimates, 5 hours in length. These conditions are an ongoing burden, the asylum process can take anywhere from a few months to a year and a half with people feeling stuck, in limbo, and with limited access to rights and freedom restricted to the island until they have an ‘open card’ granted.

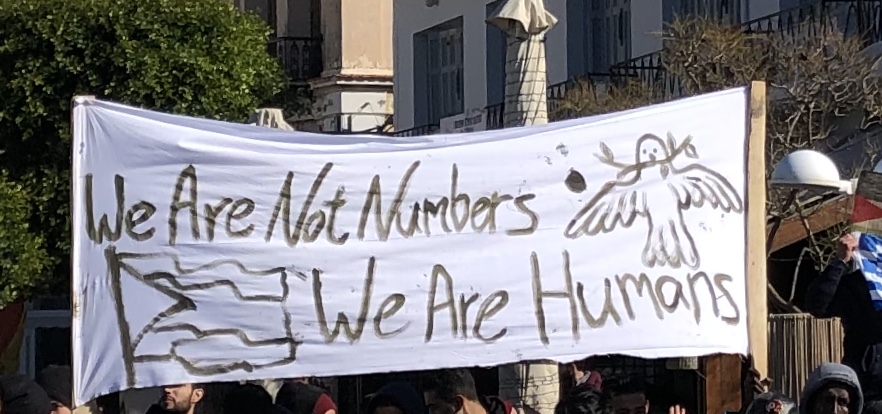

Under these conditions it is unsurprising that protests are becoming common place. The refugee population are protesting the appalling camp conditions, inadequate camp service provisions, as well as the asylum process in Greece which situates people in limbo for months, weeks, and increasingly, years. Today, things have changed and an increased police presence surrounding the Vathy Reception Centre is visible. The upper access to the camp is now heavily guarded and inaccessible. The chemical toilets in ‘the jungle’, newly installed, have been upended, creating a barricade on the main road into the camp. What is more, smoke from the rubbish that has been set fire to, billows, across the camp and mountains. While it is possible to leave the camp via the lower exit, through a single door, the loudspeaker within the reception centre, which provides the primary mode of communication between the camp management and the refugee population, tells of cancelled asylum meetings scheduled for today.

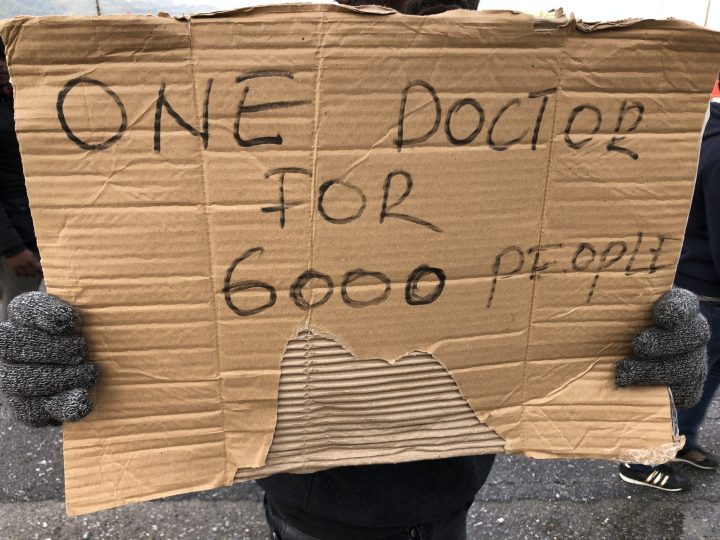

There is, within this space, a palpable tension as reception centre residents and the police mingle, waiting to see what will now unfold. The police presence is not just at the bottom and top of the reception centre, but on the roads in and out. They carry batons and some are holding riot shields. The protestors, peaceful over the last few days, ask for rights to freedom and to healthcare. Yet the mood in and around the Vathy reception centre has changed, as the restrictions on access have increased it has become tense. People are stuck on this island with little communication as to when they will be able to leave and in ever deteriorating conditions. Against this backdrop increased tensions are unsurprising. There is a need for greater awareness of the conditions on this island and greater transparency to a process that holds people here for 18 months under restrictions that take away peoples freedom.

Dr Amanda Russell Beattie (Aston University)

Dr Gemma Bird (The University of Liverpool)