Going to Worlk from the TUC [UK’s Trades Union Congress] is campaigning for a rejection of the revised Investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS tribunals in the Free Trade Agreement between the EU and the US. “The vote is back on again [at the European Parliament], scheduled for next Wednesday (8 July). But there’s been a worrying new development in the form of a dangerous compromise over Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms.

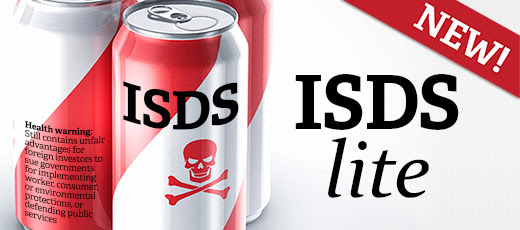

“ISDS mechanisms give foreign companies extra legal powers to challenge governments. In the past they have been used by companies to sue governments for increasing minimum wages, renationalising health services or protecting the environment.

“Campaigning MEPs had been planning to press for a stronger European Parliament attitude to TTIP and to ISDS in particular, but now the amendments that sought to strike out ISDS have been replaced by a new compromise amendment, brought by the President of the European Parliament, and several European party groupings.

“The deal’s backers say this ISDS-lite plan rules out the worst excesses of ISDS, but we’re concerned it leaves intact the fundamentally bad idea that foreign investors should get a privileged route to massive compensation payments when democratically-elected governments do something that, it could be argued in court, affects the profits of a multinational company.”

The TUC is asking people to write to their MEPs again, calling on them to reject the dangerous new compromise on ISDS in Wednesday’s vote.

Owen Tudor, Head of the TUC’s European Union and International Relations Department, explains:

“Here are ten reasons why the compromise amendment is a bad deal:

1. Although this proposal addresses some of the drawbacks of ISDS, it really isn’t an alternative to ISDS, but just a softer version, or ISDS-lite. It still provides for individual foreign investors to challenge state decisions directly, with all the problems that entails such as ‘regulatory chill’ (when Philip Morris sued the Australian Government over plain paper packaging – a case still not concluded – the New Zealand Government shelved its plain paper packaging proposals.)

2. Leaving any form of privileged investor protection in TTIP would mean that the threat to a publicly-run National Health Service remains. Corporate lawyers will still be licking their lips over the possibility of suing any government brave enough to return privatised parts of the NHS to public hands. And that applies to education, water, railways and any other privatised or part-privatised public services.

3. The compromise would provide foreign investors with compensation arrangements not available to other potential litigants (eg workers, consumers, environmentalists). It would be like restricting access to the European Court of Justice, which also oversees trans-national conflicts, to just one class of litigants, foreign investors.

4. The imbalance of access to justice which is so offensive in ISDS would remain – workers would still get what they have in the EU-Canada deal (called CETA): the possibility of a strongly worded, expert report. As ever, if that’s good enough for workers why should investors get more?

5. The costs involved in taking cases under this arrangement will mean it is only really available to big companies – so small firms will be excluded, which has led to opposition from Austrian and German small firms’ organisations.

6. The case for privileging investors like this still has not been made. How much extra investment is likely to arise? How much has been lost as a result of not having ISDS in EU-US arrangements?

7. Some of the changes proposed sound good (eg “private interests cannot undermine public policy objectives;”) but how can they be guaranteed? In practice, the courts will decide how far these principles are effected (they always do) and we can’t guarantee, once set up, that courts will do as we wish. Corporate lawyers will get creative!

8. There are still many reforms to ISDS that have been proposed which are not included in this proposal, eg that costs should be borne by the unsuccessful litigant, that litigants should demonstrate they are upholding the law before suing governments (so there will be many cases brought by disreputable companies), that amicus curiae/third party briefs will be permitted etc.

9. The move throws away the Parliament’s negotiating position with the European Commission far too early. The TTIP negotiations have years to run, and opposition to ISDS will continue to build. Rather than accept a compromise investor protection system at this stage, the Parliament should hold off until popular opposition to ISDS has made all special deals for foreign investors unacceptable.

10. Finally, the compromise amendment means that the Parliament only has the option to vote for ISDS-lite (as set out in the current draft of the Parliament’s resolution) or ISDS-liter as in the compromise, rather than the original amendment put down by MEPs like Labour’s Jude Kirton-Darling which called for excluding ISDS from TTIP altogether.

“The lengths that European Parliament politicians have gone to, responding to public concern, demonstrates how effective and influential the campaign against ISDS has become. No one in the European Parliament is now defending the sort of ISDS that has been included in the already concluded EU trade deals with Canada, Singapore and so on.

“Unions and other campaigners will be demanding those trade deals have to be scrapped or completely rewritten, and we will be building popular opposition to special rights for foreign investors, whether they’re called ISDS or not. We’ve come a long way, and losing this skirmish doesn’t mean we can’t win this trade war.”