Life and death are two sides of the same coin. No one can go through life without experiencing death, or die without experiencing life. While this appears to be a phenomenon or law of the biological world, we as beings should not be content with merely meeting our biological needs, concerning ourselves with nothing but survival. In spite of this, we as beings still find it impossible to do away with our physical form (body) or to disregard the limitations and realities that it embodies (for instance, one of the limitations and realities is that our body is incapable of existing at the same time in Hong Kong and France). The basis of life education is rooted in the understanding of, experience with and reflection on the two sides of the coin: life and death; limitations and transcendence. It is only after this recognition that we may go on to learn the roles that fate, accommodation and courage play in our journey to discover and be ourselves, and while doing so, unleash our full potential and fulfill our personality.

By Lap-yan Kung, Associate Professor Department of Cultural and Religious Studies, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Being and Non-being

Life involves not only the ensuring of survival and health but also the seeking of happiness and meaning. While survival and health seem to be of the material, happiness and meaning seem to be spiritual issues. However, in reality the two are inseparable and simultaneously embodied in our body. On the one hand, our body affects our emotions, relationships and intellectuality (with illness being one of the most concrete examples). As social beings, it is unavoidable for our body to be constructed by the environment in which we live. For instance, the acquiring of table manners in both Eastern and Western societies is a form of social and cultural construction of the body. On the other hand, our body is also the only gateway to knowing ourselves. For example, a woman’s understanding of her self begins and also ends with her body. In other words, it is the embodied self that allows us to experience that “I am my body” rather than “I have a body”. This is why we often say that treating your body well is analogous to treating your self well.

The phrase “I am my body” denotes a sense of connectedness between our being and the body. However, we have all experienced alienation of various forms and degrees between our being and body. For instance, sometimes we do not feel satisfied with the appearance of our body, believing it to be too tall, short, fat, or skinny. Other times, we abuse our body through overworking or excessive drinking. This is the transition from “I am my body” to “I have a body”. Maybe the ultimate alienation comes when our body denies our being with death, causing us to be non-being. Non-being not only threatens us with biological death but also causes a sense of helplessness and powerlessness in our search for meaning. But the truth is: death does not exist outside the embodied self; rather, it is part of what constitutes the embodied self. That is to say, even without accidents or illness, we all experience death no matter what. Even though the threat to being by non-being is an ontological anxiety of being and our fear and subsequent anxiety towards death is absolutely real and understandable, it is such anxiety that allows us to wake up to our state of being. This concept corresponds to some of our common sayings of how death makes us cherish being alive and teaches us how to live. Despite this, anxiety over death (or non-being) still keeps us on edge because more often than not, death ruins our plans and the order we are familiar with. To alleviate anxiety about death, some propose awareness training as a solution because, on understanding that death is essentially part of nature, this overcomes the threat to being by non-being, and fear is no more. But such an approach gives rise to the question: is this approach merely a self-accommodating strategy to deal with our inability to transcend non-being, a social and cultural construction of the embodied self, or is it true liberation? The truth is that we cannot really understand non-being because it is, as the name suggests, non-being. In other words, our hands are tied when it comes to attempting to lift the veil of death. However, even though non-being is indescribable in words, it is clearly felt, through its unmistakable threat of death.

As being is embodied in our physical form (body) and manifested through relationships, when everything in our life is manifested through relationships, the threats to our being are no longer limited to our own death. The termination of relationships is also a threat to our being because these relationships we have with others constitute a part of the embodied self. As a result, the death of others may pose an even greater threat to our being than our own death because when those who constitute a part of our being cease to exist, that part disappears forever and cannot be recovered. Such is one true sad fact about life. My latewife passed away sixteen years ago. When thinking of her death, I still feel a sense of helplessness. In addition, I am also reminded of the impermanence of life because her once being in my life is gone forever. The impermanence of life resulting from our inability to explain death by the law of cause and effect leads to what we call fate. The idea that we are affected by the relationships we form with those close to us can be extended to our seemingly unrelated relationships with just anyone and anything. The deaths of others who are closely connected to us are threats to our being, so are the deaths of strangers, animals and even the world per se. This explains why when witnessing innocent people being murdered or killed, we feel sad and helpless, and even experience grief. Such feelings and emotions arise not only from our demand for justice, but also from the fact that we are not simply composed of our own selves.

The Courageto Live

The seemingly opposing ideas of life and death in fact coexist, echoing what is said in the I Ching (or Book of Changes), “Alternation of the yin and yang is called the Dao (yi yin yi yang zhiweidao).” Despite this, in our existential experiences, death (non-being) clearly threatens life (being). In the face of the tension between being and non-being, are there any other possibilities other than feeling helpless and/or trying for accommodation?

The answer may be courage. In the discourse of ethics, courage is considered a virtue, a middle ground between timidity and recklessness, or between over-persistence and quitting. Paul Tillich once said that courage is “an affirmation which has in itself the character of in spite of.” Hence the courage to live is manifested in the fact that we don’t lose the will to live just because we know death will someday befall. Rather, we choose to recognize the value and meaning of our existence. As such, courage is not confined to stereotypical heroic acts or only found in the satisfaction of social values, but manifested in our bravery to keep faith, hope and love for life and embrace of the mystery of death in spite of the threat of non-being. This way, being, no longer threatened by non-being, courageously arrives at and experiences death. With courage, non-being is not a threat but an affirmation of being. However, it is worth noting that the courage to live doesn’t only entail the will to survive, but also the ability to face and accept death. One of the goals of life education is to understand life and death, and develop a sense of courage (“an affirmation which has in itself the character of in spite of”) so as to transcend limitations.

Despite the fact that the experience of being and non-being is existential, it is by no means an exclusive one. In other words, it is impossible for one to be completely unrelated to or feel nothing about the death of others, and vice versa, because being is relational. After the concern of how to handle my own death, the next question becomes “how do I enrich the life of others with my own life and death?” I have come to realize that my being here today is only made possible by (in other words, built with) the lives and deaths of so many others, including my parents, teachers, relatives, friends, and those who I’ve never met. Such a realization has led to my greatest lesson learned about life: gratitude. People generally tend to focus too much on the threat of non-being as a result of death and lose sight of ethical values towards others and gratitude for all things and beings.

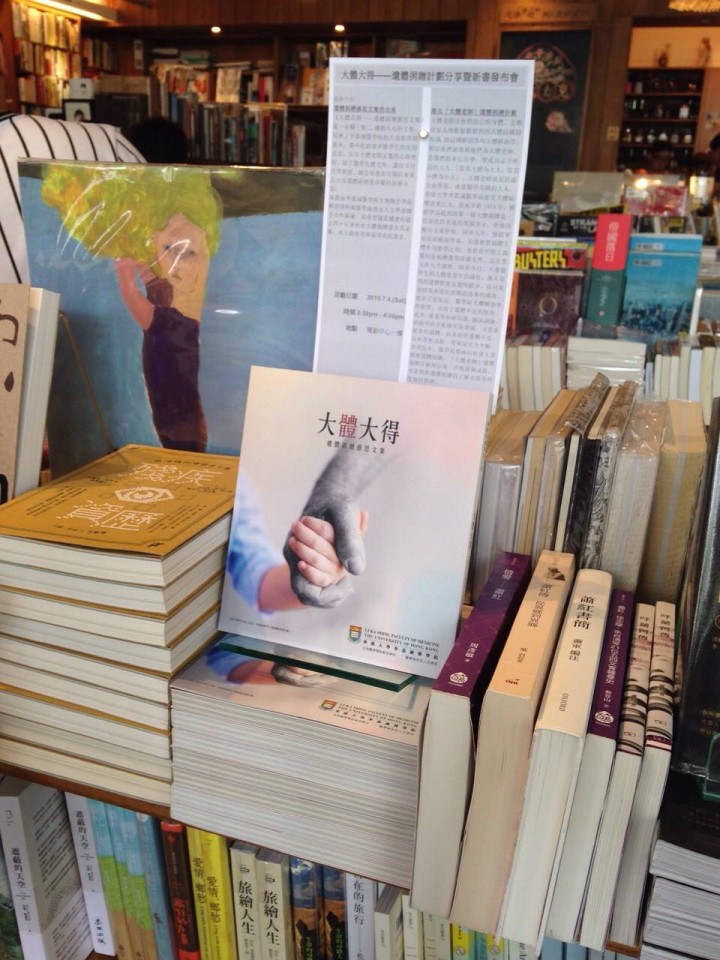

The question of “how do I enrich the life of others with my own life” has seen much discussion in the field of life education and the key is the cultivation of courage. In recent years, society has taken this idea one step further and arrived at the new question “how do I enrich the life of others with my own death.” One of the answers is body donation for medical and educational purposes. Base on the results of a survey conducted by the Institute of Medical and Health Sciences Education (IMHSE), Li KaShing Faculty of Medicine, HKU, in August 2014, Dr Lap-ki Chan said “even though death and human dissection remain an unmentionable subject in Asian cultures, we are seeing a lot of citizens of Hong Kong willing to consider the option of body donation for medical research and educational purposes. These people hope to give back to the world and contribute to others.” It is essential that we understand the decision of body donors from the perspective of courage as defined by Tillich because this is the only way we may see the rise of doctors who truly feel one with others.

Conclusion

In the end, life is a mystery rather than a question. We cannot live our life or attempt to deconstruct death with a problem-solving mindset; rather, we should enter life and death with courage so as to explore life, experience the tension between being and non-being, and in the process, unleash our full potential and fulfill our personality.

In memory of my classmate at Lutheran Theological Seminary of Hong Kong, Miss Viola Mok, who passed away on March 2, 2015.

Editor’s note:

Prof. Kung Lap Yan is an Associate Professor at the Divinity School of Chung Chi College and Director at the Centre for Quality-Life Education, CUHK. Since 2014, he has been teaching life education at The School of Nursing of Union Hospital.

This article is originally appeared in Dissecting the Meaning of Life: An Anthology of Essays on Body Donation, first published in 2015 by Wheatear Publishing Company Limited. All rights reserved by Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong. ISBN: 978-988-12841-9-8.

For more details, please visit Great Body Teacher, Hong Kong University Body Donation Program: http://www.med.hku.hk/bdp/index-e.html