On March 28, The New York City Day of Remembrance Committee (DOR), a group of volunteers, held their annual event commemorating the struggles that Japanese Americans endured during World War II. This year’s program was a tribute to the late Yuri Kochiyama & The leaders of the Redress and Reparations Movement in New York City. This August marks the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII. While the elder generation of U.S. WWII concentration camp survivors is almost gone, it was important to acknowledge Kochiyama and her cohort because of the work she did in building coalitions for social justice, including the Japanese American redress and reparations movement in NYC and nationally. Through this movement, Japanese Americans who had been wrongfully imprisoned by their own government during WWII, found their collective voices and succeeded in requiring the government to acknowledge its wrongs and in so doing, offer an official government apology and reparations.

Michael Ishii, one of the organizers of NYC DOR, gave his testimony on how Yuri inspired him and other young Japanese Americans on social justice

“Day of Remembrance” refers to February 19, 1942 when the Executive Order 9066 was signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, authorizing military control of the western United States, leading to the forced evacuation and imprisonment of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry.

Though the reason given for the mass detention at the time was “military necessity”, this argument was later discredited through documents that were later revealed by researcher, Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig, who after years of research discovered government documents proving otherwise.

Japanese Americans were rounded up, stripped of their constitutional rights, and were removed to concentration camps surrounded by barbed wire, in barren inland locations. Following the example of the U.S. government, the Canadian government sent over 27,000 Japanese Canadians to internment camps of their own, and over 2,000 Japanese Peruvians and other Latinos with Japanese ancestry in South American countries were shipped to the camps in the US. These Latin American Japanese were later used in prisoner of war exchanges with Japan and those not exchanged were stranded in the U.S. after the war ended.

Panel discussion by the redress movement activists

In the 1970’s, encouraged by many of their children who had been influenced by the civil rights movement, camp survivors organized and started the redress and reparations movement demanding an official apology from the U.S. government for unconstitutional treatment and wrongful imprisonment. In 1981 a congressional commission was appointed to investigate the U.S. government’s role in the mass detention and the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians issued its report, Personal Justice Denied, in 1983, calling the imprisonment of Japanese Americans a “grave injustice”, stating that it was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership”. Five years later the redress and reparations movement claimed a victory with the passing of the Civil Liberty’s Act of 1988 authorizing a personal apology to every camp survivor and monetary compensation of $20,000 per living survivor. Japanese Latin Americans were excluded from this legislation and were later offered separate and lesser reparations, which many survivors refused as an insult.

Throughout the US, in Japanese American communities, an annual “Day of Remembrance” is held to memorialize the experience of the people who were incarcerated and to raise awareness of the need to protect civil liberties. In recent years, the Japanese American community has spoken out against racial profiling and wrongful detentions by the U.S. government in the post 9-11 period.

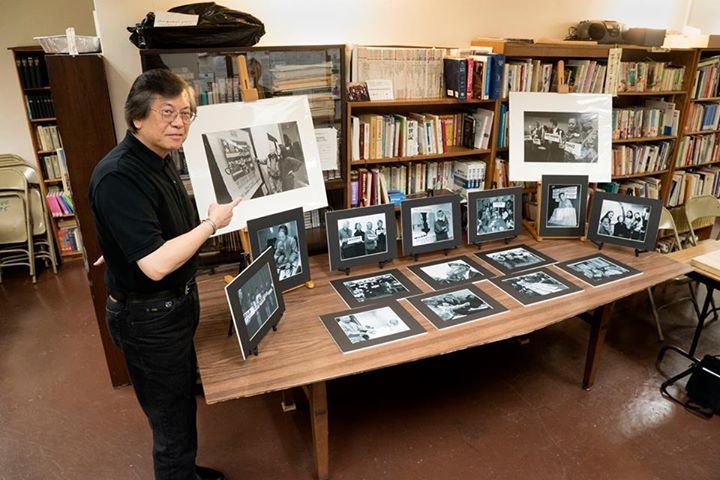

A photo exhibit of the redress movement in NYC

Reportage by Emiko Nagano