Published by the National Health Action Party (UK)

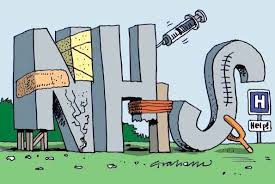

One of the main planks of our Euro election campaign is calling for the NHS to be exempted from the EU-US Trade deal, or the TTIP as it’s officially called. Most people have probably never even heard of TTIP. But we need to get informed so we understand the threat it poses to our NHS – namely making the privatisation process irreversible.

Here, international and EU trade expert Linda Kaucher of the LSE explains in detail exactly what this deal is all about and answer some frequently asked questions.

What is the TTIP?

It’s the EU/US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (also called TAFTA in the US -the TransAtlantic Free Trade Agreement)

· It is not actually about ‘trade’, but hides behind the cover of ‘trade’ because ‘trade’ is taken generally to be a good thing.

· It is promoted by big corporations, primarily the transnational financial service corporations that make up the City of London Corporation. So the UK has a central role in this despite the fact that the Trade Commission negotiates the deal.

The TTIP has the ‘usual’ free trade agreement inclusions of:

1. trade-in-goods: agricultural and manufactured -mostly about import tariff reductions, although on average these are already very low between the EU and US.

2. trade-in-services: very broad coverage, includes most of our trade, (although it’s not often admitted that ’trade-in-services’ in international trade deals is about giving service investment corporations rights in relation to govts)

3. strengthening corporate intellectual property rights e.g. patents

However the TTIP goes way beyond these usual inclusions. The main parts of the TTIP are:

A) Regulatory harmonisation: a convergence of the regulations of the EU and the US, across everything. It is regulations that define our societies and protect us from the excesses of corporations. Regulatory harmonisation, driven by big business, must mean a degradation of regulation downwards to suit corporations, to get rid of what are called, in the trade arena, ‘trade irritants’ e.g. environmental regulations.

Where harmonising is not possible, the aim is Mutual Recognitions i.e. accepting what has met the standard of the trading partner e.g. of the US even if e.g. our standards are not met.

The City of London Corporation has a secretive, International Regulatory Strategy Group.

B) The setting up of a Regulatory Co-operation Committee as part of the TTIP, to continue the harmonisation work after the TTIP is signed up i.e. the sign-up does not need to be the end point.

With this mechanism in place, the TTIP can indeed be signed up quickly, because the work will be ongoing. The model Canada /EU free trade agreement, CETA, was signed up ‘in principle’ in Oct 2013, while negotiations continue even now, and the text remains secret even now. This is the model for premature sign-up and the more formal setting up of the RCC will facilitate this.

C) The inclusion of investor state dispute settlement (ISDS) in TTIP, which will allow corporations to sue governments directly , for compensation for all profits lost from any government action (at any level of government) e.g. the introduction of environmental, public health, social or labour rights legislation.

The disputes are adjudicated by ‘arbitration’ panels’ made up of trade lawyers, judging only on values of ‘free trade’, taking no account of social, environmental or human rights values.

Where ISDS is already in place in other agreements it is shown to lead to big public payouts to corporations, or perhaps even more serious, the failure to legislate for fear of being sued, i.e. the chilling effect.

The negotiations and texts of the TTIP are secret despite the fact that they will directly affect almost a billion people directly and many more indirectly as the TTIP establishes ‘rules’ for the rest of the world.

They will be secret until the negotiations are completed. At that point, the European Parliament only has the right of assent, that is to say yes or no at the end of the process.

EU trade agreements are being ‘provisionally implemented’ by the Commission even before they come back to Member State parliaments for agreement, so this is absolutely limited to a rubber stamping process.

Trade agreements, once signed up are effectively permanent.

How will affect TTIP affect me in my everyday life?

· Protective standards across all areas are likely to be lowered. A particular area is Genetically Modified foods, access for which the EU has so far resisted but which the US, acting for big agricultural firms like Monsanto, is determined to pursue.

· Similarly EU REACH chemical safety standards are likely to be ‘harmonised’ down to the lower standards of the US.

· Car safety standards , where they differ are likely to be ‘mutually recognised’.

A fundamental difference in safety between the US and EU is that, in the EU runs on the ’precautionary principle’ , while the US runs on ‘scientific proof’. With the precautionary principle, a product is banned if it may cause harm, even if the harm lacks scientific proof. In the US the burden of proof is on the government, to prove harm, otherwise a ban cannot be imposed.

Data protection differences are another area where people in the EU are likely to see protections reduced from standard harmonisation or mutual recognition especially backed up by ISDS. New, innovative regulation becomes especially difficult.

The fact that all regulation (at all government levels) must be considered first through the prism of ‘trade’ implications, limits regulators’ ability to respond to public demand so democracy is lost to corporate power.

All this is enforced through the ISDS mechanism.

What dangers does the TTIP pose to the NHS?

The Health and Social Care Act, which has wrought such severe commercialisation changes to the NHS, was clearly prepared as part of the ‘regulatory harmonisation’ process. Although the deal was only launched this year, it has been in process for some years, with much ironed out before the launch and health mentioned as much as 3 years ago in Brussels as an early target. So the H&SC Act has already changed the NHS to a corporate-benefit public health system like that of the US.

Without a broad exemption of the NHS, the UK health service will be part of the TTIP. The services part of the deal will be ‘negative listing’ i.e. instead of listing the services that will be liberalised (positive listing), only exceptions will be identified, and before sign-up – it’s not possible to being them into the negative list later.

When the H&SC Act changes are part of a signed up TTIP, reversing the Act will not be possible because of the liberalised contracting (the many contracting opportunities in the NHS, resulting from the Act, will have been opened to transnational companies). So however disastrous these changes prove to be, it will not be possible to reverse the system of private contracting with overseas companies.

Are the main political parties worried about the impact of TTIP on the NHS?

It seem that are all are captive to the City of London Corporation which directs UK trade policy input to the EU directly (via its Liberalisation of Trade in Services – LOTIS – Committee), bypassing parliament and the UK public sphere.

Both Coalition partners are pursuing the deal as is the leadership of the Labour Party , even while promising reversals of some of the H&SC Act. There is undoubtedly concern among the lower ranks of the Labour Party.

It is in the global trade agenda that neoliberalism is being permanently fixed in international trade law so that it cannot be affected by future governments regardless of their leaning. It is not easy for any major Party to run counter to the power of transnational capital and to oppose the international ‘trade’ agenda, but that is what is needed.

Considering that the Coalition introduced the H&SC Act, and how the Labour Party when in power brought privatisation into the NHS, there does not seem much hope from within any major party.

Only pressure from outside of the party, in the public sphere and from the grass roots up, insofar as there is any residual power in that respect, can effect change.

But the feeling among civil society against the TTIP is growing, with many major groups making demands for changes, eg. removal of ISDS (particularly), public release of texts, a real jobs and living standards focus, assessment of impacts on vulnerable groups, positive rather than negative listing of services, and the exemption of the NHS from the deal. But none appear to be setting red lines, stating a time limit and a fall-back position, or if/when demands are not met. This is what is needed. Right now is a good time for this with a ready-made time-limit – there is a space now between the pre Christmas 3rd negotiating round and a mid March 4th round.